She was built to disappear.

Not in the romantic sense, not like a magician’s flourish or a ship slipping into fog for the sake of poetry, but in the colder, more disciplined sense of Cold War necessity. USS Benjamin Franklin was designed to vanish into the acoustic shadows of the ocean, to become a rumor instead of a presence, a probability instead of a target. That was the deal struck between the Navy and history in the early 1960s. If the submarine could not be found, then war itself might be kept at bay.

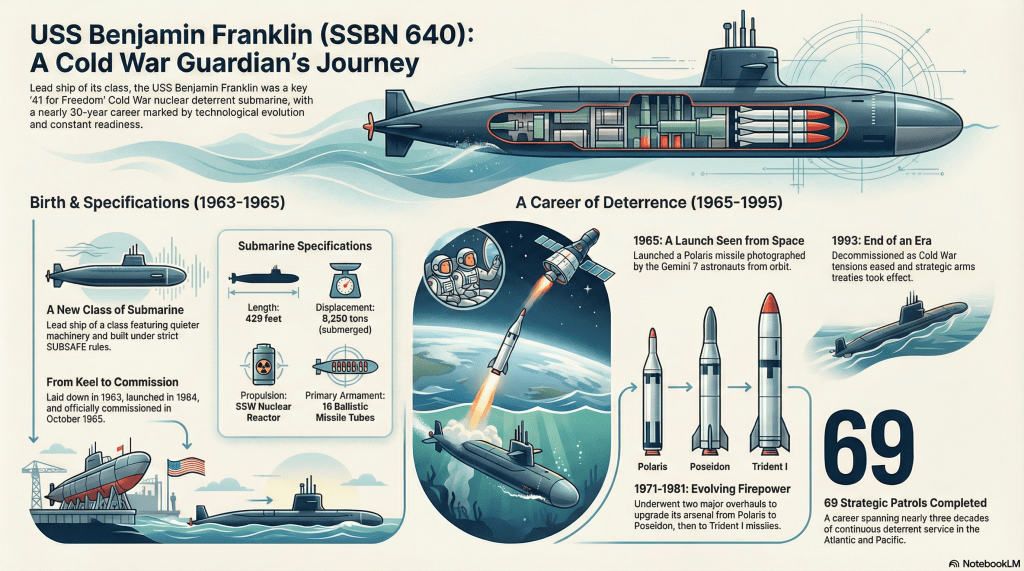

Commissioned on October 22, 1965, USS Benjamin Franklin entered service as the lead ship of her class and one of the final members of the famous “41 for Freedom,” the fleet ballistic missile submarines that quietly formed the most survivable leg of America’s nuclear deterrent. For nearly three decades, she carried that responsibility without fanfare, without public acclaim, and without a single moment when her mission became obsolete.

She was not meant to fight. She was meant to wait.

Before the submarine, there was the man, and before the man became legend, he was simply born into a world that did not yet know what to do with him. Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, the fifteenth of seventeen children in a candle maker’s household. He would never command an army or hold the presidency, yet he became indispensable to the American founding precisely because he understood systems, incentives, and human nature better than most men of his age.

Franklin was a printer, a scientist, a diplomat, a philosopher, and a relentless organizer. He understood electricity not just as a force of nature but as something that could be measured, controlled, and put to use. His famous kite experiment was less about bravado than curiosity disciplined by method. In politics, he applied the same instincts. He built alliances patiently, spoke softly, and leveraged reputation as a tool rather than a trophy.

As a diplomat in France, Franklin embodied restraint backed by credibility. He made himself indispensable without appearing threatening, persuasive without being loud. That is no small coincidence. The submarine that bore his name would operate on the same principle. It would influence history not by action but by the certainty that action was always possible.

Franklin believed deeply in preparation, in systems that worked quietly in the background, and in the idea that stability was often achieved not by force but by the credible promise of it. Naming a ballistic missile submarine after him was not symbolic window dressing. It was a statement of philosophy.

Design, Construction, and the Pursuit of Silence

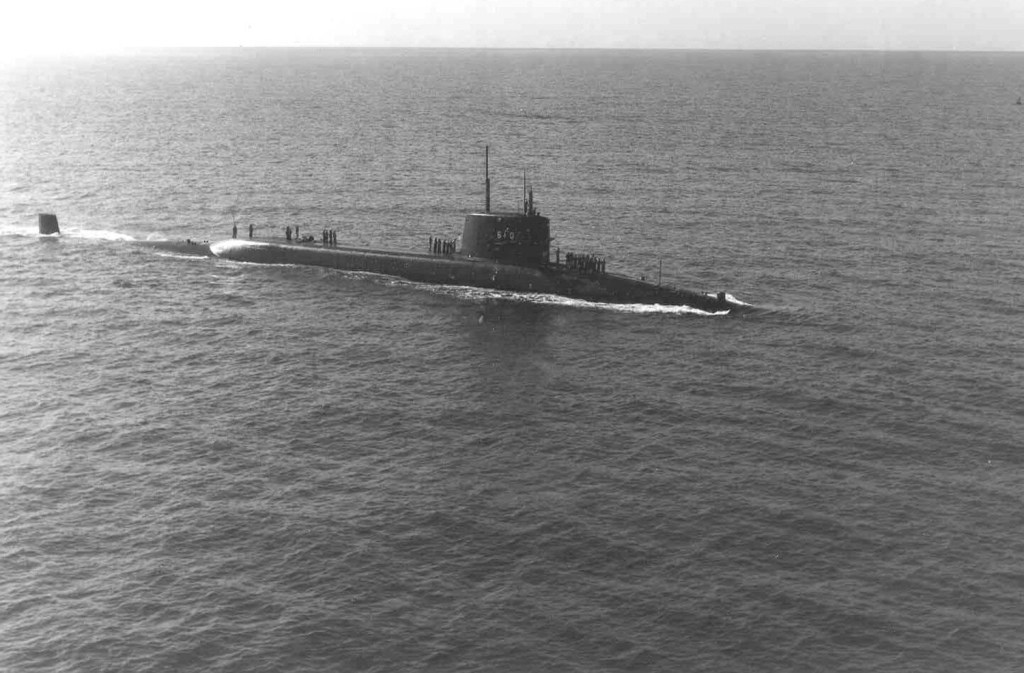

USS Benjamin Franklin was built by the General Dynamics Electric Boat Division in Groton, Connecticut, under the SCB 216 Mod 2 design. On the surface, she closely resembled the earlier Lafayette class submarines. Below the waterline and behind the bulkheads, however, she represented a deliberate evolution toward acoustic discretion.

Noise was the enemy. Every rotating machine, every pump, every shaft and turbine had the potential to betray a submarine’s position. Franklin’s design addressed this threat methodically. Turbines and propeller shafts were mounted on shock absorbing materials. Machinery spaces were isolated. Vibrations were dampened, redirected, or eliminated wherever possible. The goal was not absolute silence, which is impossible at sea, but anonymity.

She measured 425 feet in length with a beam of 33 feet. Displacement was approximately 7,350 tons surfaced and more than 8,200 tons submerged. Power came from a single S5W pressurized water reactor driving two geared steam turbines. This was proven technology, conservative by design, and chosen precisely because reliability mattered more than innovation at this level of risk.

Like all fleet ballistic missile submarines, Benjamin Franklin carried two complete crews, Blue and Gold. Each consisted of roughly 13 to 15 officers and between 120 and 130 enlisted men. The arrangement was not a luxury. It was an operational necessity. The boat could remain on patrol for extended periods while the crews rotated, preserving both readiness and sanity.

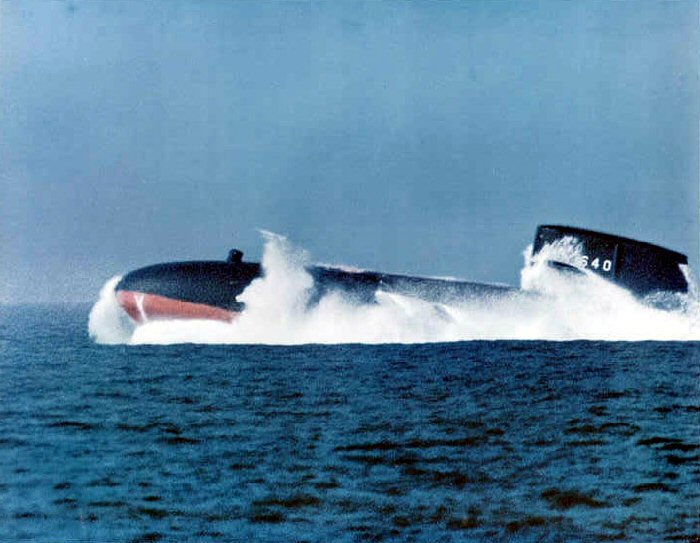

The keel was laid on May 25, 1963. She was launched on December 5, 1964, sponsored by Mrs. Francis L. Moseley and Mrs. Leon V. Chaplin. Less than a year later, she was in commission, ready to assume a role that demanded perfection and offered no applause.

Polaris and the First Patrols

Benjamin Franklin entered service at a moment when the Polaris missile system had matured from experiment to doctrine. The Navy had learned how to keep submarines on station for months at a time. The missiles were reliable. Command and control procedures were established. What remained was execution, repeated endlessly and without error.

Within weeks of commissioning, Franklin participated in one of the more quietly remarkable moments of the Cold War. On December 6, 1965, her Gold Crew launched a Polaris A-3 missile timed to coincide with the orbital pass of Gemini 7. Astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell were circling the Earth as the missile arced from beneath the sea, a fleeting intersection of two technologies that defined American power in the mid-1960s. The Blue Crew followed with a successful launch on December 20.

These were not publicity stunts. They were proof of coordination, timing, and system integrity. Everything worked because everything had to.

In April 1966, Benjamin Franklin transited the Panama Canal and joined the Pacific Fleet. Pearl Harbor became her home port, with forward deployments from Guam. By July 11, she completed her first strategic deterrent patrol. From that point forward, patrols became routine in the way that only extraordinary things can become routine when practiced by professionals.

Between 1965 and 1968, the submarine maintained a consistently high state of readiness, earning a Meritorious Unit Commendation in 1969. The award recognized sustained excellence rather than a single event. That distinction mattered. Deterrence was not about heroics. It was about endurance.

In 1970, patrols carried Franklin into the Indian Ocean. For many crew members, this meant crossing the equator and undergoing Shellback initiation ceremonies. Traditions endured even in the most modern vessels, reminders that the Navy remained a human institution, not merely a technical one.

Poseidon and Mid-Life Transformation

By the early 1970s, the strategic landscape had shifted again. Advances in missile technology made it possible to carry multiple independently targetable warheads, increasing both flexibility and deterrent value. To remain relevant, Benjamin Franklin would have to change.

In February 1971, she entered Electric Boat in Groton for overhaul and conversion to the Poseidon C-3 missile system. The work was extensive. New fire control systems were installed. Missile compartments were modified. Crew training programs were rewritten. Franklin became the twelfth submarine to undergo the conversion, part of a fleet-wide effort to maintain technological parity and strategic credibility.

The refit was not without incident. On April 11, 1972, while moored at the Electric Boat dock, Benjamin Franklin collided with a tugboat, sinking it. The submarine itself was undamaged, but the event served as a sobering reminder that risk never fully disappears, even in port.

The conversion was completed on May 15, 1972. A Demonstration and Shakedown Operation followed on June 16, when Franklin successfully launched a Poseidon missile. By December 1, she was back on patrol, now operating primarily in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Operational testing continued through the decade. On June 26, 1976, she conducted a test launch of two Poseidon missiles. Each launch was a rehearsal for a scenario everyone hoped would never occur, and each had to succeed as if the stakes were absolute.

Trident and the Long Vigil

The late 1970s brought yet another transformation. The Trident I C-4 missile promised longer range, improved accuracy, and greater strategic reach. In November 1979, Benjamin Franklin entered Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for conversion to the new system.

The overhaul lasted nearly two years. When it was complete in September 1981, Franklin emerged as one of the most capable ballistic missile submarines in the fleet. A successful Trident launch during a DASO on November 15 confirmed the upgrade. Her first Trident patrol began on April 14, 1982.

On December 18, 1983, USS Benjamin Franklin completed the 2,200th strategic deterrent patrol in the history of the fleet ballistic missile submarine force. It was her 51st patrol. Numbers like that rarely resonate outside the submarine community, but within it they speak volumes about reliability, professionalism, and trust.

In July 1985, Franklin was temporarily assigned as an attack submarine asset with Submarine Squadron 8 in Norfolk. It was an unusual role for an SSBN, but it underscored the confidence the Navy placed in her crews and systems.

From July 1986 to December 1988, she underwent a reactor refueling overhaul at Charleston Naval Shipyard. The work extended her service life and prepared her for the final phase of her career. She resumed patrols in July 1989 with Submarine Squadron 18.

Fiscal year 1990 marked a high point. Benjamin Franklin was named Atlantic Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarine of the Year and received a second Meritorious Unit Commendation. By then, the Cold War was already beginning to thaw, though few could say with certainty how it would end.

In 1993, she completed her 69th and final deterrent patrol. The mission she had been built to perform was no longer required in the same form. History had moved on.

The Human Cost Beneath the Steel

It would be dishonest to tell this story without acknowledging its cost. Like many submarines built in the mid-twentieth century, Benjamin Franklin incorporated asbestos in insulation, piping, and ventilation systems. At the time, it was standard practice. Decades later, its consequences became painfully clear.

Many crew members faced increased risks of mesothelioma, lung cancer, and other asbestos-related diseases. The enclosed environment of a submarine magnified exposure. The deterrent held, but it was carried by people whose sacrifices extended long beyond their service.

This, too, is part of the record.

Decommissioning and Legacy

USS Benjamin Franklin was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on November 23, 1993, closing nearly 28 years of service. She entered the Nuclear-Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, where dismantling was completed on August 21, 1995.

Unlike some of her predecessors, her sail was not preserved as a monument. There is no museum hull, no public walkway through her compartments. What remains instead are reunion associations, crew rosters, and the quiet understanding shared by those who served aboard her.

Her legacy is measured not in battles fought or enemies destroyed, but in decades when nothing happened. In a century defined by brinkmanship and near misses, USS Benjamin Franklin helped make catastrophe unnecessary. She embodied the paradox at the heart of deterrence. To be ready for war so that war never comes.

For a submarine named after a man who believed deeply in preparation, restraint, and quiet influence, that feels exactly right.

Leave a comment