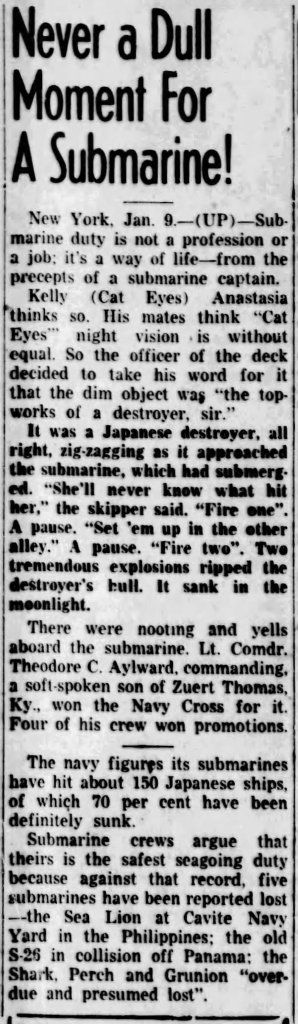

The story was told later in newsprint (January 10, 1943, Hanford, CA), folded into a Sunday paper in California, trimmed to fit a column and given a confident headline that promised reassurance to families far from the sea. It said there was never a dull moment for a submarine, and that submarine duty was not a job but a way of life. It said the night belonged to sharp eyes, steady nerves, and a skipper who knew when to act. All of that was true. None of it conveyed what the night of February 3, 1942 actually felt like aboard USS Searaven SS-196.

The Molucca Strait was black in the old way, the kind of darkness that offered no edges and no comfort. Sea and sky merged into a single surface, broken only by the low, deliberate movement of a submarine running on the surface because speed mattered more than invisibility at that moment. Searaven had not been built for romance or heroics. She had begun the war hauling ammunition and supplies toward a doomed defense in the Philippines, slipping past air raids and wreckage, learning how narrow the margins had become. By early February, those orders were finished. The boat had been told to hunt.

There was no radar picture to trust, no electronic certainty. Survival still depended on men who could see and men who could decide. On watch that night was Kelly Anastasia, known to everyone aboard as Cat Eyes, not as a nickname but as a statement of fact. His night vision had earned him something rare in wartime, unquestioned trust. When he reported a dim object ahead, bearing uncertain but moving with purpose, there was no demand for confirmation. The officer of the deck accepted it immediately. The object was the topworks of a destroyer.

The contact was Japanese, a destroyer running a zigzag course, fast and aggressive, hunting submarines rather than guarding against them. She moved with confidence born of recent victories and thin opposition. She did not slow. She did not alter course. She did not imagine that the shadow pacing her through the night was already inside her decisions.

Lieutenant Commander Theodore C. Aylward faced a choice that submariners of that era understood well. He could dive, slow the approach, and attempt a submerged attack that offered safety at the cost of opportunity. Or he could gamble on the surface, trading concealment for speed, placing his boat where discovery meant destruction. He chose the latter, not because it was dramatic, but because it was correct. A surface attack offered visibility and maneuverability. It also demanded nerve.

Searaven closed the distance carefully, timing her approach to intersect the destroyer’s zigzag pattern. The enemy ship remained oblivious, her officers confident in darkness and routine. The range collapsed. The moment arrived without ceremony.

Fire one.

The torpedo left the tube and ran clean. There was a pause that stretched long enough to feel dangerous, long enough for doubt to creep in, long enough for every man aboard to understand that once committed, there was no undoing it. Aylward did not hesitate.

Set them up in the other alley.

Fire two.

The sea answered with violence. Two tremendous explosions tore into the destroyer’s hull, ripping steel and breaking compartments open in a flash of light and sound that erased the night for an instant. The ship sank quickly, broken and helpless, sliding beneath the surface in the moonlight that finally chose to show itself. The newspaper would later record that simple fact, that it sank in the moonlight, as though the sea had been cooperative.

Aboard Searaven, discipline cracked just enough to remind everyone they were human. There were shouts and cheers, hooting and yells that spilled out before anyone could stop them. This was the boat’s first confirmed kill of the war, achieved not by caution but by judgment and speed. It mattered in ways that had nothing to do with tonnage. For a submarine that had spent the opening weeks of the war running supplies toward inevitable defeat, it marked a transformation.

The celebration ended almost as soon as it began.

Aylward ordered the boat down at once. There would be escorts. There would be questions asked in the language of depth charges and sonar. Searaven dove hard and ran deep, twisting away from the scene before the sea could turn hostile. The water closed overhead, swallowing wreckage and evidence alike, leaving only silence behind.

Months later, the Hanford Morning Journal would present the story as a reassurance. It would explain that submarine duty was a way of life, that Cat Eyes Anastasia’s vision was without equal, that the skipper had said the destroyer would never know what hit her. It would note that Aylward, a soft spoken son of Zuert Thomas, Kentucky, received the Navy Cross, and that four of his crew earned promotions. It would even include statistics, about Japanese ships hit and sunk, and then quietly list the American submarines already lost, Sea Lion at Cavite, S 26, Shark, Perch, Grunion. It would try to balance pride with honesty.

What it could not capture was the narrowness of the moment. The way trust passed without discussion from lookout to officer, from officer to skipper. The way one decision in darkness separated hunter from hunted. The way victory lasted only seconds before survival took over again.

On February 3, 1942, USS Searaven crossed a line that many boats never had the chance to cross. She did it without spectacle, without witnesses, and without apology. She saw first, struck cleanly, and vanished before the sea could respond. That was the way of life the newspaper tried to describe. The men who lived it did not need the explanation.

Leave a comment