After refitting at Saipan, Greenling sailed north as part of the tightening U.S. submarine net around Japan’s home islands. Her mission was straightforward but perilous: interdict shipping along Japan’s coastal lanes and disrupt the remnants of enemy supply traffic fleeing the Philippine front.

The patrol began with quiet days of endurance and routine, constant radar sweeps, periscope observations, and the perpetual strain of aircraft alerts. Submariners of this late stage of the Pacific War lived in the shadows of their predecessors’ successes. Japan’s navy had learned, and anti-submarine air coverage was now relentless. Greenling frequently dived to avoid detection, her log marking dozens of aircraft contacts, many close enough to rattle the boat with their depth-charges.

By early November 1944, operating off the Honshu coast, she finally found targets. On 7 November, as corroborated by JANAC records, Greenling torpedoed and sank Kiri Maru No. 8 (939 tons) and Kotai Maru (975 tons) near 34°32′ N, 138°33′ E. The deck log details careful submerged approaches, the firing of Mark 18 electric torpedoes, and two successful detonations that sent both small coastal freighters to the bottom.

The Attacks of November 7, 1944

By dawn on November 7, 1944, USS Greenling had been shadowing Japanese coastal traffic along the approaches to Shionomisaki, the southern tip of Honshu. The sea was calm, visibility good, and the crew tense. They had spent days weaving through heavily patrolled waters, their SD radar screens occasionally flickering with aircraft returns, forcing repeated dives. That morning, however, the water was clear of planes, and Commander J. D. Gerwick chose to run submerged at periscope depth, sweeping the coastline for targets.

At 0950, the sonar gang reported distant screws, medium-speed, rhythmic, consistent with a small convoy. Through the periscope, the captain made out two merchantmen escorted by a small patrol craft, all hugging the coastal traffic lane. The larger freighter bore the markings of a Maru, later identified as Kiri Maru No. 8, about 900 tons. Greenling eased ahead on an intercept course, adjusting depth to remain unseen. Her torpedo data computer hummed quietly as the plot developed.

By 1045, the range had closed to 1,500 yards. The captain ordered tubes 1 and 2 flooded. “Stand by,” he whispered. “Fire one. Fire two.” Two Mark 18 electrics slithered free. The seconds stretched. Then came two solid hits. Through the periscope, white water boiled under the target’s bow. The Maru lifted, broke amidships, and began to settle. The escort’s wake split as she turned to search for the unseen attacker, but Greenling was already slipping deeper, down past 300 feet, silent.

For nearly an hour, the submarine lay still as depth charges splashed and thudded in the distance, none dangerously close. When the hydrophones reported the escort’s screws fading away, Gerwick brought the boat back toward periscope depth. Smoke and oil marked the resting place of Kiri Maru No. 8.

That afternoon, at 1530, Greenling sighted another freighter on the same route, a single tanker of roughly 1,000 tons, later identified as Kotai Maru. The submarine shadowed it through the late afternoon haze. The patrol log notes her crew’s restraint. Gerwick chose to bide his time, setting up a textbook submerged approach. At 1640, Greenling fired a three-torpedo spread. Two fish ran true. A flash, a dull boom, and the tanker burst into flame from bow to stern. She listed heavily to port and stopped dead in the water. Within minutes the ship exploded again, then began to sink by the stern.

The log records that Gerwick remained at depth for nearly an hour, listening as bulkheads collapsed and the sounds of the dying ship faded away. When Greenling surfaced after nightfall, the only evidence of her handiwork was a burning patch of oil and drifting debris.

Those two attacks, executed within a single day off the Honshu coast, marked the climax of Greenling’s tenth war patrol. Both Kiri Maru No. 8 and Kotai Maru were confirmed sunk, adding roughly 2,000 tons to her record. For the weary crew, the events of November 7 brought both triumph and the grim reminder that Japan’s lifelines were growing ever thinner. The patrol report closes with Gerwick’s terse notation: “Targets destroyed. Withdrew to deeper water. No counterattack of consequence.”

Afterward, Gerwick took Greenling deep to evade patrol craft and aircraft. The log shows no serious counter-attack damage, only minor pressure effects. For the remainder of the patrol she hunted sporadic traffic in the same region, scoring no further confirmed sinkings but disrupting convoys and forcing diversions along the coast.

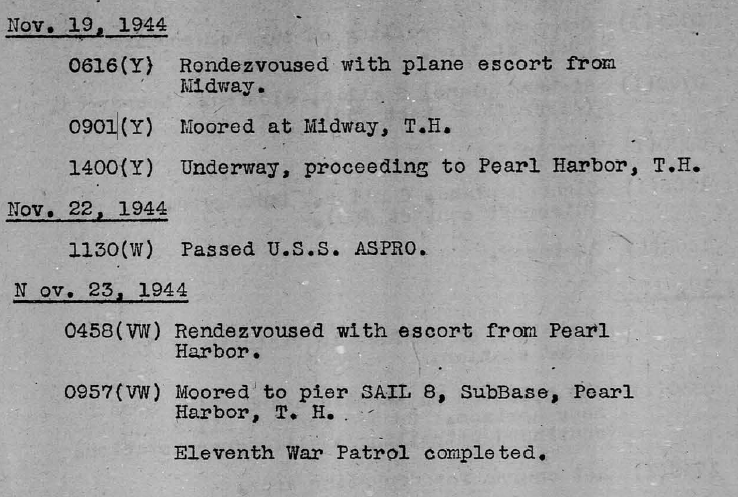

By late November, fuel and torpedo inventories were nearly exhausted, and the constant air patrols made further action unlikely. Greenling set course for Saipan, mooring there on 23 November 1944 to end her eleventh war patrol.

Though modest compared with her earlier triumphs, the patrol was deemed successful. Two confirmed sinkings, steady reconnaissance, and survival in one of the Pacific’s most dangerous patrol zones earned her crew combat recognition. Following this patrol, Greenling required significant hull work, and by January 1945 she was en route to Pearl Harbor.

Greenling’s 11th patrol encapsulated the twilight of the submarine war: fewer targets, greater risks, and a sense that victory was near but costly. Her log’s final pages close not with triumphal rhetoric, but with the weary satisfaction of a crew that had done its duty and survived the deep.

Leave a comment