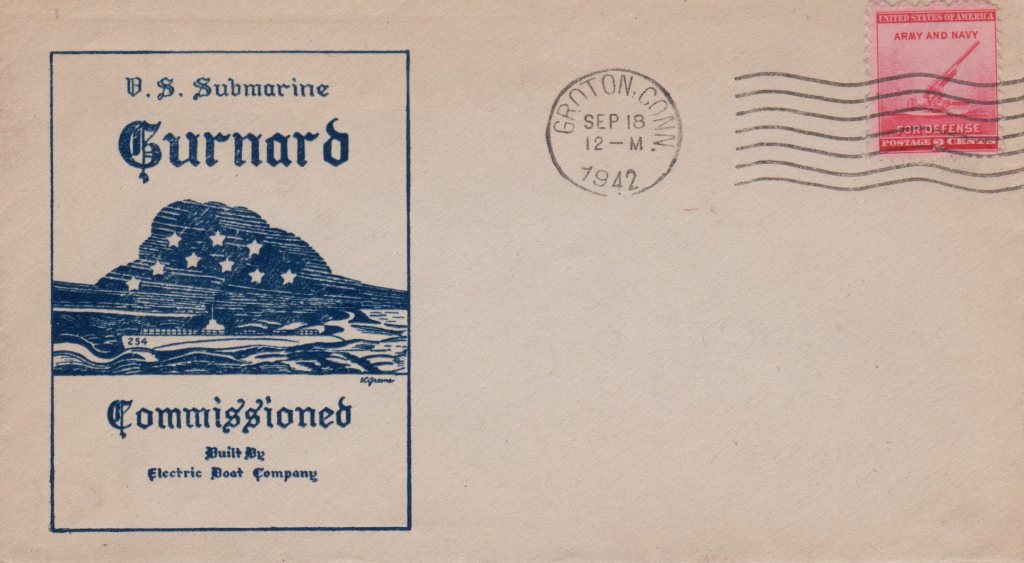

The date was September 18, 1942, when the submarine USS Gurnard was commissioned into the United States Navy. She was one of the many Gato-class submarines that slipped into the war effort during the dark mid-years of World War II, at a time when the Atlantic was still contested and the Pacific was a long way from turning in America’s favor. To her crew she was not just another boat with a fish name, she was home, she was a weapon, and she was a place where life and death mixed in with diesel fumes, sweat, and salt water. To the Navy she was a number in a long line of steel tubes being turned out of yards as fast as the nation could make them. To history, she was a fighting submarine that sank nearly sixty thousand tons of Japanese shipping, disrupted convoys, and lived to tell about it.

The Gurnard was born at Electric Boat in Groton, Connecticut, laid down in May of 1941, and launched a year later. She was christened by Mrs. William F. Halsey Jr., the wife of a man whose name would become legend in the Pacific war. By the time she joined the fleet, the war had already turned bitter. American submarines were hunting across the Pacific, often with faulty torpedoes and orders to make do. By 1942, those kinks were finally being ironed out, and the submarines were starting to bite. Gurnard was one of the wolves who would join the hunt.

Her first patrol was in the Atlantic, a relatively quiet affair in the Bay of Biscay. The Navy, still feeling its way into a global war, sometimes moved boats back and forth, searching for the best use. Nothing much happened. The Germans had the area under a tight net of air patrols and escorts. But Gurnard got her crew used to the rhythm of war patrol life, and when she headed into the Pacific, she was ready. From that point forward, her name would be tied forever to the long campaign to strangle Japan’s maritime lifeline.

On her second patrol, in the summer of 1943, she showed what she was capable of. Patrolling in the Palau region, she sighted and torpedoed the Taiko Maru on July 11. It went down under her fire, and the crew felt the rush that only comes when months of monotony and tension explode into action. The sight of a burning freighter sliding beneath the waves was grim satisfaction, a reminder of why they were thousands of miles from home in a steel cylinder. They also got a taste of the other side, as Japanese planes and depth charges came looking for revenge. It was the start of a pattern that would define Gurnard’s career: find, strike, and survive.

Her third patrol in October 1943 was one of her most productive. Off the coast of Luzon she went after Japanese shipping with a vengeance. On October 8 she sank both Taian Maru and Dainichi Maru, sending over 11,000 tons of enemy cargo to the bottom in a single day. The periscope view of fat freighters rolling over, keeling to one side, and then breaking up was seared into the minds of the men who watched. They were hunters, and the war was becoming a business of tonnage. The more you sank, the closer the war moved toward victory.

By Christmas Eve of 1943, Gurnard was prowling off the coast of Japan itself, where she scored a pair of kills in icy northern waters. On December 24 she hit Seizan Maru No. 2 and Tofuku Maru, and badly damaged another transport. The Japanese escorts fought back with depth charges, rolling drums of TNT over the side in patterns designed to crush the hull. The boat bucked, lights went out, bolts strained, but she held. When she surfaced again, she had lived through it. Many crews would tell the same story. It was a war of nerves, of listening to the propellers and counting the seconds until the next explosion. Sometimes the charges walked right over you and you were still alive. Sometimes they didn’t.

But the patrol that secured her place in history came in May of 1944. By then Gurnard was based out of Fremantle, Australia, operating deep into the South Pacific. Her quarry was the infamous Take Ichi convoy, a group of Japanese transports carrying reinforcements and supplies. Convoy warfare was brutal. The Japanese had learned to group ships together with destroyer escorts, but that made them fat targets for submarines willing to risk the counterattack. On May 6, Gurnard crept into position. Torpedoes ran true, and three transports went down: Aden Maru, Amatsuzan Maru, and Taijima Maru. Nearly 20,000 tons lost in one stroke. Japanese soldiers bound for New Guinea drowned by the thousands. The escorts responded with fury, dropping nearly a hundred depth charges in the hunt. Gurnard twisted and turned, diving deep, blowing ballast, silent running as the screws of the destroyers churned above. She made it out. The toll on the enemy was devastating. The loss of those reinforcements helped tilt the balance in New Guinea and the surrounding campaigns.

Later in that same patrol she sank the Tatekawa Maru on May 24, bringing her total tonnage even higher. By then she had earned her reputation. Every submarine wanted to sink ships, but few had a single patrol with four large freighters confirmed. Gurnard’s crew took pride in the accomplishment, and the Navy decorated her accordingly. Patrol reports filed back to headquarters made dry reading, but for the men who lived it, every line was a heartbeat.

Her sixth patrol in mid-1944 was less dramatic, though no less dangerous. She operated in the Banda, Molucca, Celebes, and Sulu Seas, looking for targets. She damaged one ship but brought home no sinkings. War was like that. You could spend weeks chasing shadows, dodging patrol craft, sweating in the humidity of a closed tube, and still have little to show for it. The crew called it “going stale.” But they kept the edge, knowing that the next patrol might bring fortune again.

On her seventh patrol in the fall of 1944, she returned to form. On November 3 she sank Taimei Maru west of Labuan, Borneo, another large freighter sent to the bottom. A few days later she laid mines off Borneo, another dangerous mission. Mine-laying submarines were essentially laying their own death traps in enemy waters, sneaking in close to plant explosives that could claim ships weeks later. Gurnard did the job and escaped. Her patrol report recorded the task with official brevity, but the crew knew how close they had come to disaster if they had been discovered.

Her eighth patrol, from December 1944 to February 1945, was devoted to reconnaissance work. She prowled the South China Sea, eyeing Cam Ranh Bay and other enemy strongholds. No kills, but information was valuable. As the submarine war wound down, the boats were being used for scouting, lifeguard duty for downed airmen, and special missions. The Japanese merchant fleet was already bleeding to death. There were fewer ships to find.

By the ninth and final patrol in the spring of 1945, Gurnard was hunting in barren waters. The Japanese had lost most of their transport capacity, and submarines often returned with empty logs. She completed the patrol with no kills, returned to Pearl Harbor, and was sent back to the States for overhaul. By war’s end, she was a veteran of nine patrols, credited with sinking ten Japanese ships totaling nearly 58,000 tons, and damaging several others. She had survived heavy counterattacks, contributed to the destruction of critical Japanese convoys, and written her name in the rolls of successful boats.

After the war she was decommissioned and placed in reserve, but like many wartime submarines, she was not immediately scrapped. In the Cold War years she served as a training boat at Pearl Harbor and later at Tacoma, Washington, helping to school a new generation of sailors in the ways of undersea warfare. Her hull was no longer front-line material in the age of nuclear power, but her lessons were still valuable. Finally, in the early 1960s, she was struck from the register and sold for scrap. A fighting boat reduced to metal for the yards. But her legacy lived on in the men who had served aboard her, in the patrol reports that still exist, and in the tonnage lists that mark her contribution to the war effort.

What makes Gurnard’s story so compelling is not just the numbers, though the numbers are impressive. It’s the texture of the life lived inside her steel. The smell of diesel and sweat, the condensation dripping on bunks, the endless coffee pots, the sound of the klaxon when diving, the hush when the order for silent running was given, the men stripped to the waist in tropical heat, listening for the screws of destroyers above. It’s the fear when depth charges hammered the hull, the prayers muttered under breath, the sigh of relief when the screws faded away. It’s the letters written and never sent, the jokes told to break the tension, the long stretches of monotony punctuated by moments of sheer terror. Every submarine story is like that, but each boat adds its own chapter.

Gurnard’s chapter is highlighted by the Take Ichi attack, one of the great submarine strikes of the war. The Japanese learned again that their convoys were vulnerable, that American submarines would risk everything to break their supply lines. Thousands of Japanese troops died without ever reaching their destination. The strategic effect was enormous. A submarine that could cripple an army’s reinforcement convoy was more than a nuisance. It was a decisive weapon.

After the war, her story faded into the background. Submarine history is crowded with famous names like Tang, Wahoo, Barb, and Cavalla. Gurnard doesn’t always make the top tier of legend, but among submariners her record is respected. Ten confirmed sinkings is nothing to dismiss. Her patrol reports remain a source for historians who want to know what the undersea war really looked like. Her crew, like so many others, returned home, built families, and carried with them memories of cramped bunks, roaring diesels, and the long silence of patrols. Some spoke of it, some did not. But all of them had lived in the belly of a steel fish named Gurnard, and they knew what she had done.

Today, the name Gurnard is still remembered in Navy lists, though the boat herself is long gone. Her battle flag, festooned with silhouettes of ships, told the story in stitched images. Her place in history is secure. Commissioned in September 1942, she lived through the crucible of the Pacific, contributed to the strangling of Japanese commerce, and came home. Few can ask for more from a fighting ship.

When we look back on her history, we should remember that these submarines were built by thousands of hands in yards across the country, launched with ceremonies, and sent into a world where most Americans would never know their names. Gurnard was not a battleship or a carrier. She didn’t host admirals or earn headlines. She did her job quietly, in the dark, striking at the lifelines of an enemy half a world away. That was the essence of the submarine war, and Gurnard exemplified it.

She was, in the end, a hunter, a survivor, and a reminder that in war sometimes the quietest weapons speak the loudest.

References

CombinedFleet. (n.d.). SORG: USS Gurnard (SS-254) patrol tabulation. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.combinedfleet.com/sorg.php?q=254

Maritime Park Association. (n.d.). World War II submarine war patrol reports: USS Gurnard (SS-254). Maritime.org. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://maritime.org/doc/subreports.php

Naval History and Heritage Command. (n.d.). USS Gurnard (SS-254). In Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/g/gurnard-ii.html

NavSource Naval History. (n.d.). USS Gurnard (SS-254) submarine photo archive. NavSource.org. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08254.htm

Uboat.net. (n.d.). USS Gurnard (SS-254) of the US Navy – American submarine of the Gato class. Uboat.net. Retrieved September 17, 2025, from https://uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/3000.html

United States Navy. (1942–1945). USS Gurnard (SS-254) war patrol reports. [PDF files]. Naval History and Heritage Command archives.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, September 15). USS Gurnard (SS-254). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Gurnard_(SS-254)

Leave a comment