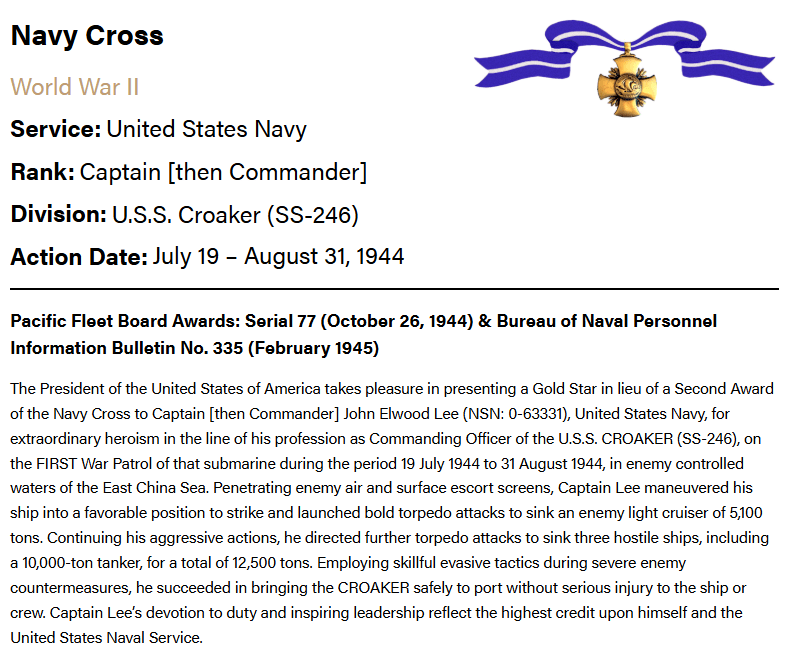

In the summer of 1944, USS CROAKER SS-246, embarked on her first war patrol, leaving Pearl Harbor in July and pushing deep into the East China and Yellow Seas. The early days were a mix of training sharpened by caution, with sporadic contacts and long stretches of empty water. By mid-August, she had skirted mines, traded information with other submarines, and patrolled close enough to hostile shores to feel the reach of Japanese air and sea patrols. It was in this tense environment, between the fourteenth and seventeenth, that CROAKER struck two decisive blows, demonstrating both the skill of her crew and the deadly precision of a well-handled submarine.

By mid-August 1944, USS CROAKER was well into her first war patrol in the East China and Yellow Seas. She had already engaged merchantmen and warships, but the next few days would deliver two of her most decisive victories.

On August 7, 1944, CROAKER was patrolling submerged off the southern tip of Koshiki Shima when the sound operator reported distant echo ranging at 1100 hours. Minutes later, the periscope revealed a Japanese KUMA-class light cruiser zigzagging radically on a northerly course.

CROAKER maneuvered for a stern-tube shot. At 1121, four torpedoes were fired from the stern, range about 1,300 yards by periscope and 1,000 yards by sound, with track angles between 130 and 140 degrees starboard. Immediately after firing, the cruiser made a sharp zig away, threatening to spoil the attack. Moments later, she turned back toward the original course, crossing the path of the torpedoes.

At 1126, through the periscope, the crew saw the result. A violent explosion erupted on the starboard side abreast the mainmast. Flames and water surged high above the masthead. The cruiser slowed, her stern settling, and a heavy starboard list began to develop. A “NELL” type bomber circled overhead, while a Japanese submarine chaser closed from astern.

By 1132, the stern was almost submerged, the list increasing rapidly. It was clear that the single torpedo, likely assisted by the detonation of the after magazines, would finish the job. At 1140, crew members in the control party and the Royal Navy observer, Lieutenant Commander Lakin, were given a chance to view the sinking ship. Color motion picture film recorded the scene.

At 1150, a massive secondary explosion was heard, followed by the sounds of the ship breaking up over the next five minutes. The submarine chaser began echo ranging, but CROAKER was already taking evasive action, retiring to the southwest.

In less than half an hour from first sighting to final breakup, the KUMA-class cruiser had been struck down by a single, well-placed torpedo, removed from Japan’s order of battle in a rapid and decisive encounter.

August 14 opened under a calm sky with haze lying low along the Korean coast. In the morning, a Japanese trawler passed southward and was noted but not engaged. At 1345, a puff of smoke appeared on the southern horizon, bearing one hundred ninety six degrees true, but the contact never materialized. By nightfall, CROAKER had turned back toward the coast.

At 2050, the SJ radar picked up a contact at 10,000 yards. The crew went to battle stations. By 2142, the periscope confirmed the target: a Japanese PC-class patrol craft making nine knots on a steady 180°T course. At 2146, with the TDC solution checking perfectly, one Mark 18 torpedo was fired from 1,800 yards, set for a depth of two feet, gyro angle 103° starboard. The run lasted ten seconds before impact. The hit was a perfect bull’s-eye, immediately followed by another explosion, likely from the target’s own depth charges. The patrol craft disintegrated in a single flash, scattering fragments that fell into the water around CROAKER as she turned away.

Three days later, in the early hours of August 17, radar contact was made at 17,000 yards. At 0318, the target was sighted at 7,000 yards: a very large, engines-aft merchantman, estimated 525 feet long, heavily laden, likely an ore carrier or tanker. CROAKER maneuvered ahead. At 0320, a salvo of three Mark 18 torpedoes was fired from 1,800 yards, each set to six feet depth. Tube #6 was at gyro 69° starboard, tube #5 at 70°, tube #4 at 72°. One torpedo ran erratic, one hit one quarter of the ship’s length from the bow. The ship slowed to between three and five knots.

At 0330, CROAKER fired her remaining three torpedoes. Tube #1 at gyro 92° starboard, tube #2 at 112°, tube #3 at 112½°. One hit struck one quarter length from the stern, settling it to the bottom. Two minutes later, the entire ship sank. The hits were all contact detonations with Mark 18 torpex warheads.

These actions took place amid constant hazards. On the morning of the fourteenth, a floating mine with a red-painted casing was sighted at 300 yards, its position recorded as latitude 36°41’N, longitude 125°11’E. The waters in which CROAKER operated were narrow, heavily patrolled, and seeded with such dangers.

The attack on the patrol craft removed a mobile antisubmarine threat. The destruction of the large merchantman denied Japan a valuable hull and cargo during a time when both were desperately needed. In each case, firing solutions were executed cleanly, torpedo runs were properly timed, and results were immediate. By the time CROAKER withdrew from the coast on the seventeenth, her log reflected two confirmed sinkings over four days, carried out with precision and without detection.

Following the destruction of the large merchantman on August 17, CROAKER shifted to lifeguard duty in support of B-29 air raids. She patrolled assigned stations off the Chinese and Korean coasts, scanning for downed airmen and keeping a wary watch for Japanese ships and aircraft. Several floating mines were sighted and avoided, their positions recorded for navigation safety.

On August 20, she received word that the scheduled airstrike was delayed. The following day brought repeated aerial sightings, forcing frequent dives. Between August 21 and 22, CROAKER observed a ten-ship convoy with four escorts near the Ryukyu Islands, but unfavorable position and enemy air cover prevented an attack. She transmitted a contact report to assist other submarines in the area.

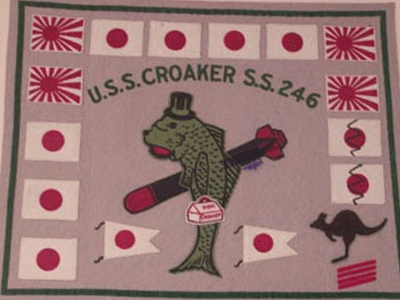

From August 23 onward, CROAKER turned toward Midway, transiting dangerous waters still patrolled by Japanese aircraft. She arrived safely at Midway near the end of the month, having completed her first war patrol with two confirmed sinkings — a patrol craft and a large merchantman — plus valuable reconnaissance and lifeguard service.

USS Croaker (SS-246) First War Patrol Report, 13 July – 31 August 1944, Submarine War Patrol Reports, 1941–1945, Record Group 38: Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations; National Archives Catalog. National Archives and Records Administration. Online version available at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/139738610; accessed August 11, 2025.

Narrative by David Ray Bowman FTB1(SS), 08.11.2025

Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975. ISBN 0-397-00753-1 (Standard Edition), ISBN 0-397-01089-3 (Deluxe Edition).

Roscoe, Theodore. United States Submarine Operations in World War II. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1949. ISBN 0-87021-731-3. Page 384

Leave a comment