The clock had barely ticked past midnight when USS Hammerhead (SS-364) slipped beneath the waves, 10,000 yards ahead of a Japanese convoy steaming through the Gulf of Thailand. The crew knew what was coming. Their orders were clear: close in, identify the targets, and attack. Every man aboard had drilled for this moment. Now it was time to put steel and nerves to the test.

By 2:29 AM, they surfaced again, cautiously threading their way back into position. The ocean was eerily quiet, too quiet for comfort. Contacts in this sector were scarce, and the decision was made to try something risky. Hammerhead would launch a surface attack. Bold? Absolutely. Dangerous? Without question. But the captain wasn’t about to let the enemy slip away under cover of darkness.

At 3:45 AM, the approach began. All eyes were on the targets now, a small convoy creeping through the night, unaware of the predator stalking them. The escort ship kept close to the lead freighter, almost shielding it. The Hammerhead’s skipper noted the pattern and made the call. Go in astern of the escort and launch three torpedoes at each freighter. No room for error.

By 0400, the enemy escort dropped back, sliding into position off the second freighter’s beam. The targets were identified as two Sugar Charlie Sugars, likely displacing between 660 to 880 tons. These were coastal freighters, hauling supplies to a crumbling empire. The escort was a patrol boat or subchaser, probably no more than 250 tons, but with just enough punch to ruin your whole day if it got lucky.

At 4:08, Hammerhead unleashed her first spread. Three Mark 18 torpedoes aimed square at the lead ship. Range: 2,100 yards. Track: 78 degrees port. Depth: two and a half feet. Every man aboard held his breath.

Moments later, the second target got its turn. Three more torpedoes, this time Mark 18s, fired at a slightly closer range of 1,800 yards. Hammerhead’s attack pattern was tight and disciplined. The escort, just 1,200 yards off the starboard bow, swung toward the submarine and back again. The crew braced for retaliation. Then came the silence.

No hits.

Frustration hung in the air like diesel smoke. Whether the torpedoes ran too deep, veered off course, or simply malfunctioned as they so often did in those days, the result was the same. The enemy convoy steamed on, completely unaware that death had brushed past them.

By 4:15, the torpedo rooms were a hive of activity as crews reloaded, sweating in the cramped spaces and shifting torpedoes aft. The captain ordered an end-around maneuver, another attempt to get ahead of the convoy and try again.

At 0700, Hammerhead submerged again, 10,000 yards ahead of the convoy’s projected path. They waited in silence, listening for screw beats, praying for another chance.

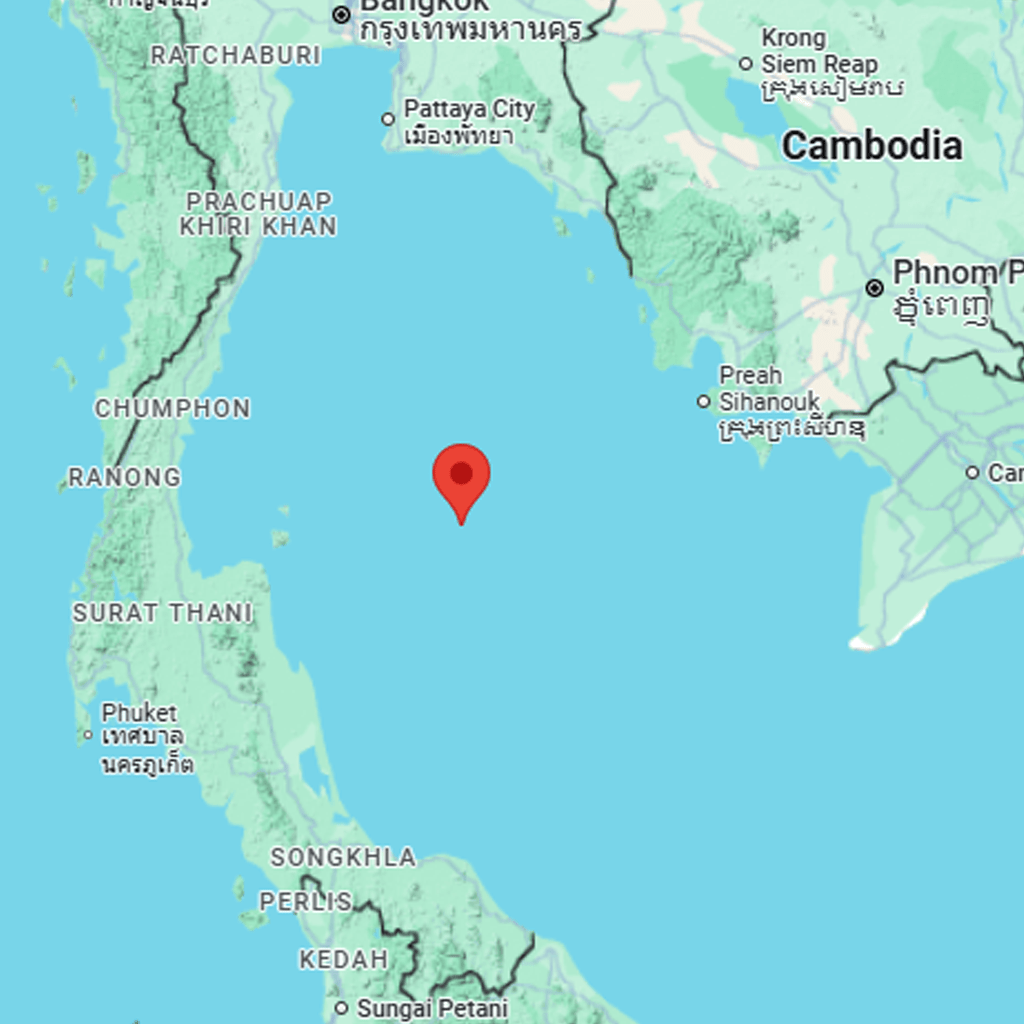

At 1200 hours, they came up again. Latitude 9 degrees 26 minutes North, Longitude 101 degrees 42 minutes East. Still no enemy in sight. They pushed on, hoping to catch the tail of the convoy.

By 1449, the sub surfaced again. Still hunting.

At 1600, Hammerhead was back on the scent, pursuing what remained of the convoy. Then, at 5:15 PM, danger appeared not from the sea, but from above. Lookouts spotted two floatplanes, low and deliberate in their pattern. Air cover. The worst kind of company. The planes were only 12 miles off. There was no time to wonder if they’d been seen. By 5:57 PM, Hammerhead slipped back below the waves.

They surfaced again at 7:21 PM, cautiously checking the skies. The air was clear, but the sense of being hunted lingered.

Later that night, the captain reported the day’s events to CHARR, BRILLFISH, and SEA SCOUT. But even that communication turned uncertain. At 9:57 PM, radar picked up interference. SEA SCOUT and BRILLFISH vanished from the screen, swallowed by electronic distortion. The last traces of contact faded away. For the rest of the night, Hammerhead was on her own.

She had fired six torpedoes and scored no hits. She had tracked a convoy for hours, danced with death in the form of enemy air cover, and still walked away in one piece. That was submarine warfare in 1944. Sometimes you hit. Sometimes you missed. But you never stopped hunting.

And the next morning, July 11, Hammerhead found something that stirred questions and speculation. Surfacing under the rising tropical sun, the crew investigated two separate patches of wreckage from the previous day’s engagement. It was silent evidence that perhaps not all their torpedoes had missed after all. They found and sank four empty lifeboats, bobbing on the current like forgotten memories. There were no bodies, no cargo, no flags. Just silence and debris. No items of interest were recovered, but the implication lingered. Maybe one of those six torpedoes had found its mark in the darkness after all.

And so, Hammerhead pressed on, hunting in the shadowy margins of war.

War is rarely as clean or certain as the reports make it sound. Bullets miss. Orders get misheard. Bombs fall short. And beneath the waves, where steel sharks hunted in silence, even truth itself could drown.

During World War II, the United States Navy’s submarine force was feared for its aggression and effectiveness, but also notorious for one odd pattern: submarine captains routinely overestimated their kills. In the heat of a torpedo run, watching explosions through a fogged periscope, many skippers were convinced they had sunk enemy ships that later turned out to have sailed on unscathed. It wasn’t dishonesty so much as chaos. Torpedoes that missed looked like hits. Ships that burned didn’t always go down. Depths played tricks. And sometimes, a good skipper saw what he needed to see to justify the risk his crew had just taken.

After the war, as Allied analysts scoured captured Japanese records, they found that some celebrated sinkings had never happened at all. Dozens of enemy vessels listed in war patrol reports as sunk were, in reality, still very much afloat when the guns fell silent. It was an uncomfortable truth, but a necessary one.

And yet, just to keep things interesting, there were also stories that ran in the opposite direction.

Such is the case of USS Hammerhead (SS-364) on the night of July 10, 1944. Operating in the Gulf of Thailand, where targets were already scarce and far between, she encountered a small convoy, two cargo ships with a subchaser escort. Her crew executed a textbook attack, launching two spreads of three torpedoes. One aimed at each freighter. They tracked the shots. Waited for the telltale flashes. Heard nothing. Saw nothing. The convoy never wavered. No explosions, no fire, no chaos. Just ships carrying on, as if they hadn’t been attacked at all.

In the official log, the result was clear: no hits.

Frustrated, the captain ordered reloading and attempted another end-around maneuver. It came to nothing. Air cover arrived, and Hammerhead had to dive deep and let the targets slip away. On the surface, it looked like a wasted opportunity, six torpedoes gone and no damage done.

But the next morning, the sea offered a whisper of something else. Surfacing under the tropical sun, Hammerhead encountered wreckage. Debris. Four empty lifeboats. No bodies. No flags. Just silence. The crew wasn’t sure what to make of it. They logged the discovery, noted it without fanfare, and moved on.

Only after the war did the full picture come into focus.

Japanese shipping records, matched against Hammerhead’s patrol location and the timing of the attack, revealed that the torpedoes hadn’t missed after all. Quite the opposite. That night, Hammerhead had sunk two enemy vessels: the Sakura Maru, a 900-ton cargo ship, and the Nanmei Maru No. 5, a small tanker displacing 834 tons. Both went down shortly after the attack. The convoy must have absorbed the loss in silence, with the escort maintaining course and formation to give the impression of safety.

What the crew believed to be a failure was, in fact, a deadly success.

It’s a perfect example of how the fog of war cuts both ways. For every overstated kill claimed in the heat of battle, there was a Hammerhead, a quiet, bruised patrol that accomplished far more than its captain ever realized. It’s also a reminder that even in a world of logbooks and torpedo data computers, some truths only surface after the shooting stops.

History, like the ocean, holds its secrets tightly. And sometimes, the only way to find them is to dive deeper.

Deck Logs, 1941–1978, USS Hammerhead (SS-364), July 10–11, 1944. Textual Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group 24. National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/74823190

Narrative by David Ray Bowman FTB1(SS) 07.08.2025

Leave a comment