The sun had barely set on June 30, 1942, as USS Sturgeon continued her patrol northwest of Cape Bojeador, slipping beneath the waves at dawn and surfacing at dusk as she had done for days. The ocean was quiet, routine. But just after 10 PM, the monotony broke. The watch spotted a darkened ship to the south, cutting through the sea under the cover of night.

At first, the angle of the sighting made it seem like the vessel was heading north, but careful observation quickly corrected that. She was moving west at high speed, clearly having just exited Babuyan Channel and making for Hainan. This was no dawdling freighter. She was moving fast, at least 17 knots, and zigzagging to avoid detection. A valuable target.

Sturgeon came alive. Her engines roared to full power. Every man on board understood the urgency. The boat turned west in an all-out attempt to get ahead of the target. For over an hour and a half they chased, but the ship held its lead. The range hovered around 13,000 yards, just out of reach. It looked hopeless. But then, around midnight, their luck turned. The target slowed. Speed dropped to about 12 knots. That was the opening Sturgeon needed.

By 1:46 AM on July 1, Sturgeon had maneuvered into position and dove to prepare for an attack. Through the periscope, the target loomed even larger than they had anticipated. She wasn’t just a freighter. She was big, too big to risk with anything less than certainty.

Sturgeon was still about 5,000 yards off the ship’s track, but managed to close 1,000 of those yards. Given the target’s size and the limited number of forward tubes available, the decision was made to use the stern tubes. They loaded four torpedoes with full 700-pound warheads. The order was given.

At 2:25 AM, four torpedoes slipped silently into the black water. Four minutes later, one struck home, just abaft the stack. The impact was unmistakable. Within six minutes, the ship was nearly vertical, bow up. By 2:40 AM, she was gone, swallowed by the sea stern first. A few lights flickered on deck just after the blast, but there was no sign of power, no call for help, only silence and the sound of rushing water.

Sturgeon surfaced at 2:50 to recharge her batteries and scan the area. They believed the vessel might have been the Rio de Janeiro Maru or something very much like it. She had been a large one. Massive. Still, there was no nameplate in the dark. No cries, no wreckage, no clue. Just another kill in the book, or so they thought.

In retrospect, the confidence was striking. Even at 4,000 yards, a long shot under any standard, the torpedo data computer operator, Lieutenant Nimitz, had called it before the torpedoes even struck. “We won’t have to use any more,” he said. “One of those will get him.”

And he was right.

Not all the torpedoes hit. As had happened during a previous attack on June 25, the crew noted that at least two of the missed torpedoes detonated as they sank. Likely, the pressure at depth crushed the warheads. The sound operator picked them up clearly. But by then, the mission was complete.

USS Sturgeon had sent the Montevideo Maru to the bottom of the sea, There was no way for the crew of Sturgeon to know what or who had been aboard. The ship had been unmarked. There had been no indication she was anything but a legitimate enemy transport. For the men aboard Sturgeon, it was a textbook engagement. A successful attack. A well-earned strike against the enemy.

History, however, would come to remember it differently.

They were packed below like forgotten cargo, hundreds of men and boys who’d survived the fall of Rabaul only to be herded aboard a Japanese freighter. No one told them where they were going. There was no Red Cross marking on the ship. No escort. Just steel bulkheads, stifling heat, and the ever-present scent of oil, sweat, and fear. It was June 22, 1942, and the Montevideo Maru was preparing to sail.

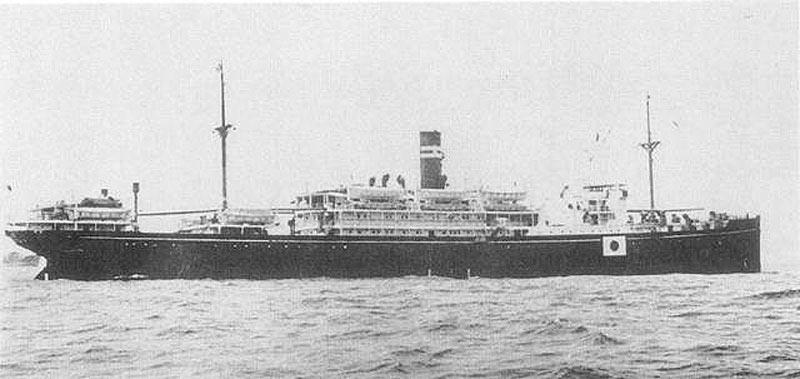

She wasn’t a warship. Originally built in 1926 in Nagasaki, the Montevideo Maru had once ferried passengers and mail between Japan and South America. But when war erupted, she was drafted into military service. By that June, she was assigned a grim task: transporting captured Australian military personnel and civilians, prisoners of war taken after the swift and brutal Japanese capture of Rabaul in January. It was a victory that cost Australia dearly, and the price was still climbing.

The men loaded onto the Montevideo Maru came from Lark Force, a small Australian garrison stationed in New Britain, along with civilian administrators, missionaries, and tradesmen. The Japanese had made no attempt to separate combatants from civilians. To their captors, they were all the same, spoils of conquest. Most were locked deep in the holds. There was little ventilation. Water was scarce. There was no expectation of comfort, let alone survival. In typical fashion for what became known as “hell ships,” these men were simply human cargo, nameless, faceless, and dispensable.

But there were names. Fathers. Brothers. Sons. Over 1,000 of them.

On the night of June 30 to July 1, the Montevideo Maru was quietly steaming northwest, off the coast of the Philippines, heading for Hainan Island in China. She traveled alone, without protection. The Japanese command didn’t think she needed any. After all, who would know what she carried?

Below the waves, USS Sturgeon (SS-187), an American submarine on patrol, was hunting for enemy ships. She spotted the Montevideo Maru and tracked her through the night. The silhouette was unmistakably Japanese. There were no Red Cross markings. There was no indication that the ship carried prisoners. To Sturgeon, this was a legitimate military target.

At 2:29 in the morning, torpedoes were fired. At least one struck home. The Montevideo Maru was fatally wounded. Within minutes, she slipped beneath the waves.

There were no cries for help from the Australians. They never had a chance. Locked below decks, they drowned in darkness. Those who made it to the surface were left to the sea. Of more than a thousand prisoners aboard, none survived. Only seventeen members of the Japanese crew were rescued. It was over in eleven minutes.

No one knew at the time. The Japanese did not report the incident to the Allies. For three years, families in Australia held out hope that their sons, their husbands, their brothers might still be alive in some distant camp. It wasn’t until October 1945 that confirmation arrived. By then, the war was over. The grief had calcified.

This was, and still is, Australia’s greatest maritime tragedy. More Australians died in the sinking of the Montevideo Maru than in any other single incident at sea. Yet for decades, the story remained shrouded in silence. There were no commemorative parades. No newspaper retrospectives. No Hollywood scripts.

Just silence. And memory.

In a bitter twist, it was friendly fire that claimed these lives. Not a Japanese execution squad or a forced death march. It was the fog of war. An American submarine captain did his duty, made the logical call based on the facts available, and unknowingly condemned over a thousand innocent men to a watery grave. It’s a reminder that war rarely gives us clean hands. Even our victories come laced with sorrow.

It would take 81 years before the ship was found. In April 2023, after decades of searching, a team led by the Silentworld Foundation located the wreck of the Montevideo Maru more than 13,000 feet below the surface of the South China Sea. She rests now in darkness, her holds still sealed, her passengers never returned. But at least now we know where they are. And we can say they are not forgotten.

There are memorials in Rabaul. In Ballarat. In Canberra. And there should be in Bremerton too. Because this isn’t just Australia’s tragedy. It is the story of every sailor who ever climbed into a submersible hull and sailed off not knowing what waited beyond the horizon. It is the story of what happens when war’s machinery consumes the innocent along with the guilty. And it is a reminder to all of us, particularly in the submarine service, that our silent duty has never been without cost.

They say the prisoners were singing as the ship sank. “Auld Lang Syne,” some reported. A final hymn to each other. To the lives they left behind. To the memory that we’re now left to carry.

Let us never forget them. Not because they were martyrs. Not because they were saints. But because they were men, our kind of men. And they deserve to be remembered.

Leave a comment