In the final week of February 1944, the USS Grayback was still hunting, and that fact alone tells you something about the boat and the men aboard her. She had already spent nearly a month stalking the shipping lanes of the East China Sea, slipping between patrol routes and aircraft arcs, rising at night to recharge batteries and diving by day into that dim, red-lit world every submariner understands. The air would have been thick with diesel and machinery oil, the rhythm of the engines as familiar as breathing, the routine of watch rotations steady and practiced. Her tenth war patrol had begun on January 28, when she departed Pearl Harbor under Commander John Anderson Moore, and by mid-February she had once again proven herself to be what the Navy built her to be: a long-range predator operating far inside hostile waters.

The men aboard knew that rhythm. They had done this before. Submarine warfare is patience more than fury, geometry more than chaos. You calculate angles, study target motion, wait for the right moment, and trust that the steel tube you have fired will run straight and true. By the third week of February, however, something had subtly shifted. Grayback was winning decisively. And in submarine warfare, decisive victories carry their own quiet consequence.

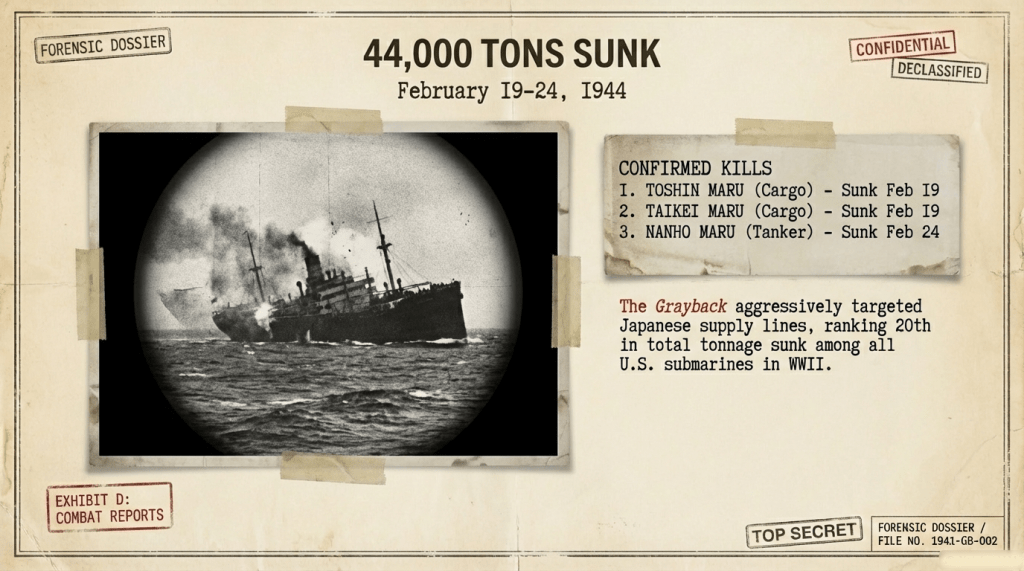

On February 19, she found her first targets of that final week. Two Japanese cargo ships, Toshin Maru and Taikei Maru, crossed her path. In the confined mathematics of torpedo solutions, positioning is everything, and Grayback maneuvered carefully, fired her spreads, and watched through the periscope as both ships were sent to the bottom. There would have been no cheering in the control room, no dramatic celebration. If you have ever stood watch in tight quarters while waiting for the sound of impact, you know that success is acknowledged quietly. Damage estimates are recorded. Gauges are checked. The boat remains alert. Submariners measure their victories in tonnage and silence, and once the sea had closed over the wreckage, Grayback slipped away as she always did.

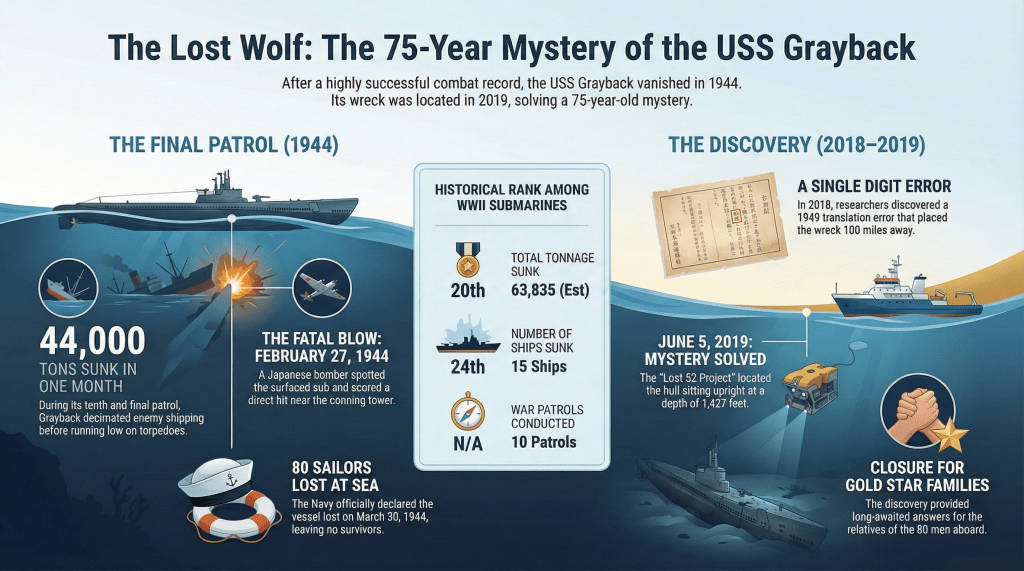

Five days later, on February 24, she struck again. This time the target was the tanker Nanho Maru, and strategically that mattered even more. Oil was the bloodstream of Japan’s war effort, and every tanker sunk tightened a supply chain already under strain. Grayback attacked and succeeded, damaging additional shipping in the process. By that point, her patrol report would soon claim approximately 44,000 tons of enemy shipping destroyed during the cruise. That was not an inflated boast. It was a remarkable total for a single patrol and cemented Grayback’s standing among the most effective submarines in the Pacific theater.

But torpedoes are not limitless. Every successful attack reduces the inventory. The arithmetic of destruction always works in both directions. By February 25, Grayback transmitted what would become one of her final messages. The report was triumphant in tone, confirming the sinking of tens of thousands of tons of enemy shipping, yet it also included the detail that mattered most to those plotting the patrol’s next phase: only two torpedoes remained aboard. Two torpedoes in the vastness of the Pacific represent a slender margin, and submarine headquarters made the logical decision. Grayback was ordered home to Midway Atoll with an expected arrival date of March 7. From a distance, it seemed routine. A successful patrol had concluded, ammunition was nearly exhausted, and it was time to return for refit and resupply.

The geography, however, was anything but routine. To reach Midway, Grayback would have to pass near Okinawa, and by early 1944 those waters were among the most heavily patrolled in the region. Japanese land-based aircraft operated from nearby airfields, and anti-submarine tactics had grown steadily more effective since the early years of the war. Aircraft hunted more confidently. Surface escorts were more vigilant. Submarine captains understood that proximity to enemy-held territory significantly increased the likelihood of contact. Grayback’s path home was not an open highway across empty ocean but rather a thread drawn through a tightening web of patrol routes and air coverage. Anyone who has ever plotted a return transit through contested waters understands how narrow that thread can feel.

On February 26, the web tightened further. Japanese records later indicated that land-based naval aircraft attacked a submarine in the area that day. The submarine survived the encounter, but the details remain sparse. We do not know precisely what Grayback endured in that engagement, whether she sustained structural damage or whether equipment was jarred loose in ways that were not immediately visible. Submarines of that era were tough, but they were not invulnerable. A near miss could deform hull plating. A shockwave could knock out instrumentation or introduce stresses that would only later reveal themselves. Even if Grayback escaped outright destruction that day, she was operating in increasingly dangerous waters and under increasing pressure.

The following day, February 27, she encountered yet another target. The freighter Ceylon Maru came within reach, and Commander Moore faced a decision that has quietly echoed ever since. He could conserve his last two torpedoes and focus entirely on bringing his crew safely back to Midway, or he could strike one more blow while the opportunity presented itself. Moore was not a reckless officer. He was a decorated leader who had earned three Navy Crosses and had pioneered coordinated submarine attack tactics. He believed in aggressive action when it served the mission. He chose to attack.

Grayback fired her final two torpedoes, and Ceylon Maru was sent to the bottom. With that act, Grayback achieved one more success and simultaneously stripped herself of offensive capability. She was now a submarine without torpedoes navigating heavily patrolled waters under enemy air power. In terms of warfighting effectiveness, she had extracted maximum value from her patrol. In terms of survivability, her margin had narrowed to almost nothing.

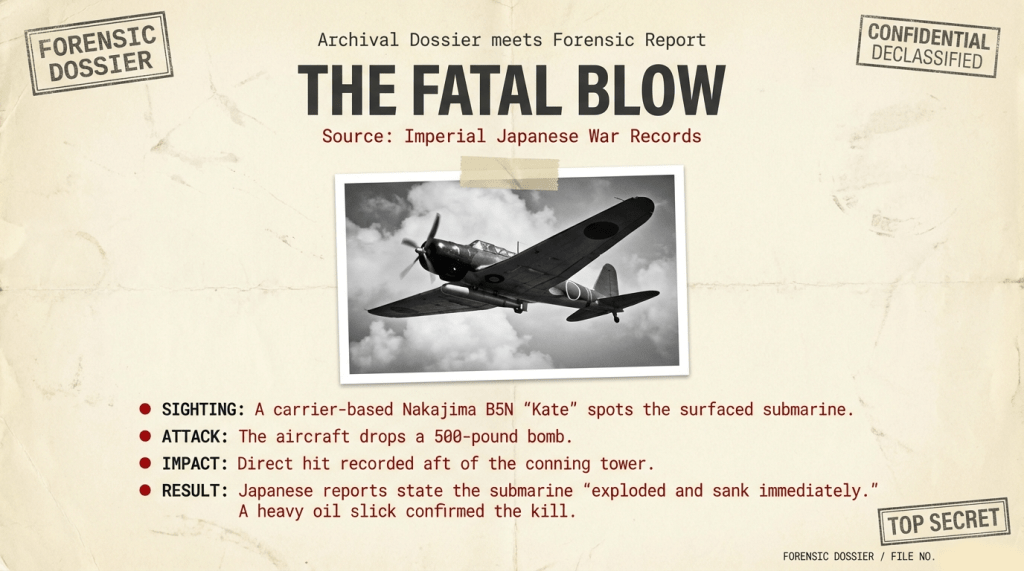

Japanese wartime records provide the clearest account of what followed. A carrier-based Nakajima B5N bomber, known to Allied forces as the “Kate,” sighted a surfaced submarine near Okinawa on February 27. Submarines of the Tambor class were designed primarily as surface vessels that could submerge temporarily, and they were faster and more comfortable on the surface. Grayback may have been recharging batteries, making speed, or dealing with the aftermath of the previous day’s attack. Whatever the reason, she was visible.

The aircraft attacked, releasing a 500-pound bomb that struck aft of the conning tower. Japanese reports state that the submarine exploded and sank immediately. Surface craft in the vicinity followed with depth charges where air bubbles were observed rising to the surface. Eventually, a heavy oil slick spread across the water, grim confirmation in the language of naval warfare. To the Japanese, the engagement was recorded and closed. To the United States Navy, Grayback simply failed to arrive.

March 7 passed without her appearance at Midway. At first there would have been watchful waiting. Submarines occasionally arrived late, and radio silence was standard practice. As days passed and no word came, concern hardened into realism. On March 30, 1944, USS Grayback was officially declared lost, and eighty officers and men were listed as missing, presumed dead. Families received telegrams that conveyed certainty and uncertainty in the same breath. There was no grave to visit, no coordinates to mark on a chart. The sea had taken her, and the exact location of that loss remained unknown.

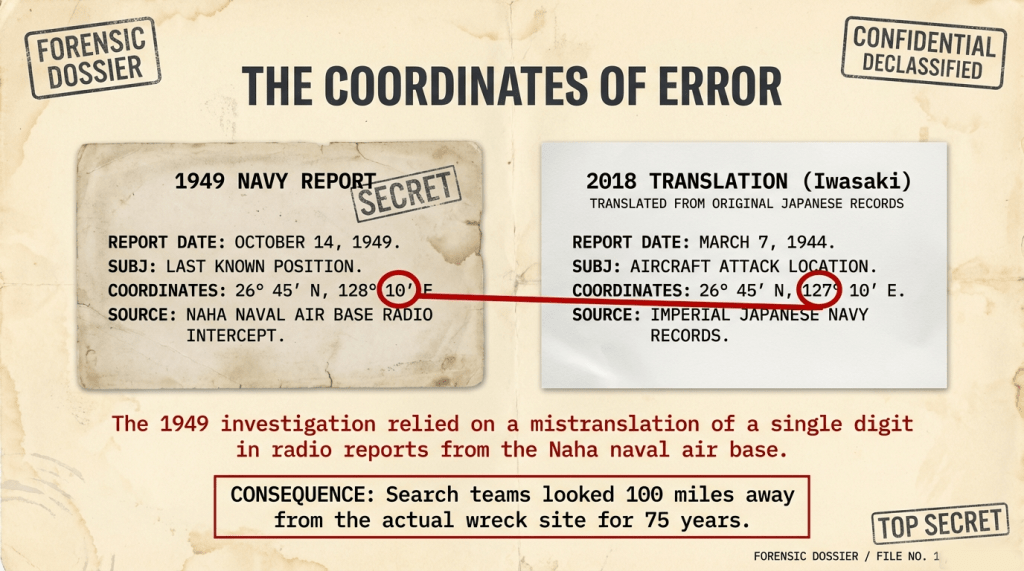

In 1949, the Navy reviewed lost submarines using translated Japanese records captured after the war. Coordinates from the Okinawa attack were plotted, and Grayback’s presumed loss location was recorded. Yet a single digit in the longitude had been mistranscribed during translation. That one error shifted the search area roughly one hundred miles from the actual wreck site. For decades, the mistake went unnoticed, and search efforts focused on empty water while Grayback rested elsewhere on the seabed. History often turns on dramatic events, but sometimes it turns on something as simple as a misplaced number.

It was not until 2018 that researcher Yutaka Iwasaki revisited the original Japanese documents and identified the discrepancy. The corrected coordinates placed the likely wreck site closer to Okinawa than previously believed. In 2019, explorer Tim Taylor and the Lost 52 Project launched an expedition using autonomous underwater vehicles to survey the revised area. On June 5, 2019, at a depth of 1,427 feet, the search team located a submarine sitting upright on the ocean floor. The damage aft of the conning tower matched the historical account of a bomb strike, and the deck gun lay some distance from the hull. On the bridge, a plaque confirmed beyond doubt what lay before them: SS-208.

The final week of Grayback’s life emerges not as a sudden collapse but as a steady continuation of the mission she had been given. From February 19 to February 27, she struck repeatedly, sinking four confirmed targets and reporting massive tonnage destroyed. She continued hunting even after being attacked from the air and chose to make one final offensive move with her last two torpedoes rather than withdraw quietly. That decision, viewed in context, reflected the aggressive doctrine that had made the U.S. Submarine Force so devastating to Japanese logistics during the war.

Today, Grayback rests as a protected war grave off Okinawa. The eighty men aboard remain on eternal patrol beneath 1,427 feet of water. Success and catastrophe occupied the same narrow stretch of sea, separated by hours and a single bomb. For seventy-five years, the ocean concealed the precise coordinates of that convergence. Now we know where she lies, and for those who understand what it means when a submarine does not return, knowing matters. It closes the chart, even if it cannot soften the loss.

Leave a comment