He did not set out to be a hero. Most submariners did not. They signed on for steady work, for a trade, for the promise of learning a machine well enough that it would not kill them. Frank Nelson Horton belonged to that quiet fraternity of men who understood engines the way farmers understand soil. He knew how things were supposed to sound, how they smelled when they were healthy, and how to tell when trouble was coming before it arrived at full speed.

The irony is that history remembers men like Horton precisely because they never sought remembrance.

Frank Horton entered the United States Navy before the war had revealed its full appetite. By December 1941, he was already in Manila when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, a detail that matters because it places him not on the margins of the Pacific war but squarely inside its opening shock. From that moment on, Horton would spend nearly two years in submarines operating in enemy waters, a stretch of service that newspapers at home would later describe with understatement that bordered on awe .

He was a motor machinist’s mate, a rating that did not lend itself to glamour. The engines did not care about rank or medals. They demanded attention, precision, and patience. In a fleet submarine, the engines were life itself. They charged the batteries, powered the surface runs, and decided whether a boat could outrun danger or would be forced to dive and pray. Horton’s job was to make sure the engines answered the bell every time.

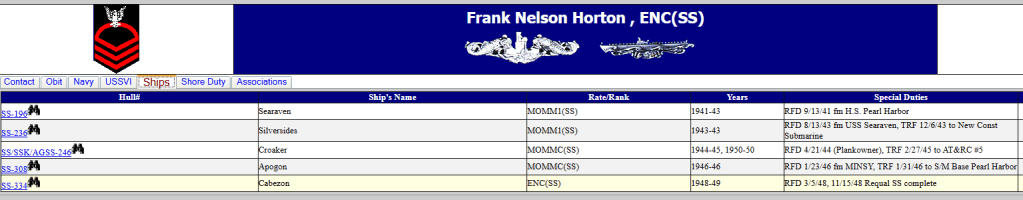

That responsibility followed him from boat to boat. He served aboard multiple submarines during and after the war, including Sea Raven, Silversides, Croaker, Apogon, and Cabezon, moving steadily from wartime duty into the long, quieter vigilance of the early Cold War years. But during the war itself, it was Sea Raven and Croaker that shaped him.

By January 1944, Horton was home on leave in Wichita, Kansas, visiting his mother and relatives. The local Evening Eagle ran his photograph on the front page under a headline that now reads like something from a pulp novel: “Visits Japan in Sub.” It was not exaggeration. Horton had completed successful patrols off the Japanese coast, missions that placed him among the comparatively small number of submariners who took the war directly to the enemy’s doorstep .

The article noted, almost casually, that he had been in submarine duty for the past two years and had participated in successful patrol runs for the Allies. It mentioned that his wife, a member of the Women’s Army Corps, was stationed at Fort McClellan in Alabama. It spoke of upcoming schooling in Cleveland before another return to submarine duty. The rhythm of the piece mirrored the rhythm of his life. Duty, brief leave, training, back to sea.

What that front page article in 1944 could not capture was what submarine duty actually meant.

Horton himself explained it plainly. Life on a submarine had its good points and its bad, he said. One of the bad points was not being in a safe place when there was a crash dive. He recalled being on a ladder during such a maneuver, falling, along with others, and breaking his wrist. It was a moment that likely lasted seconds but imprinted itself permanently. In a steel cylinder dropping rapidly into the depths, gravity and momentum were unforgiving companions. The fact that Horton spoke of it without bravado suggests a man who accepted danger as a condition, not a badge .

There was another episode, more dramatic, that followed him home in print. Horton had been part of a submarine crew that rescued a group of Australian fliers stranded on a Japanese-infested island in the South Pacific. The operation required multiple trips, carrying injured men suffering from malaria and wounds, hauling them aboard under conditions that left no margin for error. Submarines were not designed for humanitarian missions, but war does not respect design intentions. The rescue succeeded, and Horton was there for it .

These were not isolated adventures. They were the texture of the Pacific submarine war, a campaign fought in silence, patience, and long stretches of fear punctuated by moments of decisive violence or unexpected mercy. Horton did not write memoirs or seek speaking tours. His record survives because newspapers noticed him when he came home, and because later in life someone noticed his garden.

That garden is where the story turns, and it turns gently.

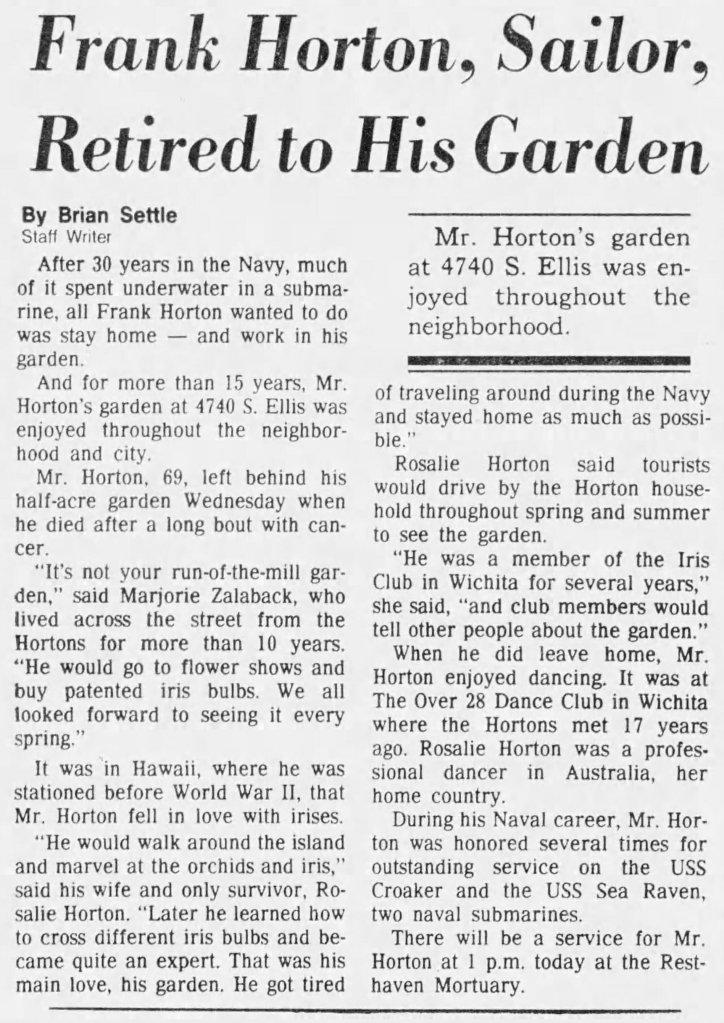

After more than thirty years in the Navy, much of it spent underwater, Frank Horton retired. He did not seek the ocean in his leisure. He sought soil. At 4740 South Ellis in Wichita, he built a garden that became quietly famous in the neighborhood and beyond. Tourists would drive by in spring and summer to see it. Club members would talk about it. Neighbors would wait for the irises to bloom.

The Wichita Eagle, writing in May 1983, described a man who had left behind a half-acre of flowers when he died after a long bout with cancer. He was sixty-nine. The article carried a simple headline that said everything the Navy never could. “Frank Horton, Sailor, Retired to His Garden”.

The details matter. Horton had fallen in love with irises and orchids while stationed in Hawaii before World War II. He walked around the island marveling at them, according to his wife, Rosalie. Later he learned how to cross different iris bulbs and became quite an expert. He joined the Iris Club in Wichita. He attended flower shows. He bought patented bulbs. He talked plants with the same seriousness he once applied to engines.

This was not a hobby. It was a vocation of peace.

There is something deeply human in the symmetry of it. A man who spent his youth coaxing life from diesel engines in steel hulls spent his later years coaxing life from the ground. The patience required was the same. The attention to detail was the same. The acceptance that some things flourish and some fail no matter how carefully you plan was the same.

Even his marriage carries the imprint of a life shaped by travel and chance. He met Rosalie at the Over 28 Dance Club in Wichita, long after the war. She was a professional dancer from Australia, the country whose fliers Horton had once helped rescue in the Pacific. History does not insist on such connections, but it occasionally allows them. They stayed home as much as possible during his later Navy years, preferring roots to ports.

The Navy did not forget him either. During his service, Horton was honored several times for outstanding performance aboard Croaker and Sea Raven. These were not ceremonial posts. Croaker and Sea Raven were working boats, their crews defined by competence rather than celebrity. To be recognized aboard them meant something real .

It is tempting to read symbolism into everything, to imagine that the quiet care of a gardener somehow redeems the violence of war. History resists such neat resolutions. What can be said, plainly, is that Horton carried his discipline forward without carrying his bitterness. He did not retreat into nostalgia or grievance. He built something living and let others enjoy it.

Submariners are often remembered for what they sank. Frank Horton deserves to be remembered for what he sustained.

He sustained engines that kept men alive under crushing pressure. He sustained crewmates through monotony and fear. He sustained a marriage that bridged continents. He sustained a garden that outlived him, at least in memory, and gave pleasure without asking anything in return.

The Pacific war consumed young men at an industrial scale. Those who survived often carried the war home with them in ways that never made headlines. Horton’s way of carrying it was to cultivate beauty. Not as an escape, but as a continuation of care.

In that sense, his life fits squarely within the best traditions of the submarine service. Submariners have always understood that survival depends on stewardship. You take care of your boat, your machinery, your shipmates, because neglect is fatal. Horton simply applied that lesson to the land when the sea no longer required him.

He served his country well. He loved his flowers fiercely. And in the end, those two facts sit side by side without contradiction.

That is not poetry. It is history, at its most honest.

Leave a comment