The story of the submarine USS Billfish begins quietly enough, like so many others of her time. She was a Balao-class boat, built at Portsmouth Navy Yard and commissioned in April of 1943, one of the many sleek steel predators that would come to define the silent war beneath the Pacific. Her skipper was Commander Frederick Colby Lucas Jr., a 1930 graduate of the Naval Academy, seasoned by years in the service but untested in the chaos of combat. On paper, Lucas was the model officer of his generation, steady, methodical, and dutiful. In reality, he was about to face the one test that reveals more about a man than any résumé ever could.

In the film, The Caine Mutiny, the narrator tells us that there has never been a mutiny aboard a United States Navy ship. Technically, that is true. But that does not mean there have not been incidents that tested the strength of men and the limits of command. These stories are hard to tell because they touch something we would rather not face. We like to believe that every man or woman who wears dolphins can be trusted completely, that the pressures of the deep never crack the surface of human courage. Yet history reminds us that even the best can falter. What happens when a submarine captain loses his nerve in combat, and what happens when the truth is uncovered sixty years later, are the questions at the heart of this story.

-ȸ

After a brief shakedown cruise and a routine first patrol, Billfish reached Fremantle, Australia, that bustling refuge of the Pacific submarine fleet. Fremantle was a strange place, full of laughter and exhaustion, where the young men who lived underwater for weeks at a time came up for air, whiskey, and the company of anyone who could remind them that the world still existed beyond the steel pressure hull. By the end of October 1943, Billfish was ready for her second war patrol. No one aboard suspected it would become one of the most quietly extraordinary voyages in submarine history.

The morning of November 1 found her sailing north with USS Bowfin and the destroyer Preston, conducting brief training exercises in voice radio coordination. There was little to distinguish that departure from a dozen others. They drilled, they tested equipment, and they crossed into the tropics under a hard blue sky. Their assigned hunting ground lay in the Makassar Strait, that narrow waterway between Borneo and Celebes where Japanese shipping moved in endless convoys. The route was treacherous even without the enemy, hemmed in by islands and shoals, patrolled by alert escorts. To survive there required instinct, composure, and a captain’s unshakable calm.

Lucas had experience, but none of it under fire. He had commanded training boats off New London, served on staff, and taught others how to fight wars he had never seen. By temperament he was careful, precise, and anxious to do things by the book. He believed in procedure, and procedure, he thought, would see them through. His engineering officer, Lieutenant Charles W. Rush, was of a different breed. Younger, more seasoned in battle, he had already completed several patrols aboard USS Thresher. Where Lucas relied on caution, Rush trusted intuition. Below decks, the crew respected him for his steadiness and quiet confidence.

Billfish slipped through the Lombok Strait under moonlight and entered the Makassar Strait. The sea was calm, the air heavy with tropical heat. Men stood their watches, checked the radar, and waited for something to happen. On the evening of November 10, the crew spotted a number of native fishing craft in the distance, sails bright against the fading sun. They seemed harmless enough, but some suspected they might be coastal spotters for the Japanese. No one could know for sure. In these waters, information was as deadly as torpedoes.

At dawn on November 11, 1943, the sea lay smooth and empty. Billfish was running on the surface at fourteen knots, her diesels steady. At 0920, the watch sighted a destroyer-type vessel about eight miles off, bearing directly toward the submarine’s periscope. The contact was reported immediately. Lucas was called to the bridge. He studied the distant speck through his binoculars, then shrugged. It was probably a coincidence, he said, a patrol craft on an unrelated course. Rush disagreed. The ship was closing fast, he warned, and her angle on the bow was zero. That was not a coincidence. It was an attack run.

Moments later the sonar began to sing. The telltale pings echoed through the hull. The enemy had found them. Lucas ordered a dive to two hundred feet. The boat slipped under, rigged for silent running. For a few tense minutes all was quiet except the hum of the motors. Then the first pattern of depth charges exploded overhead. The concussion slammed through the ship, lights flickering, instruments rattling loose from their mounts. Pipes burst, gauges shattered, and men were thrown from their stations. Water sprayed through leaky seals and fittings.

Rush steadied himself in the control room. Years of experience told him what to expect. He gave calm orders, balancing the planes, trimming ballast, and keeping the boat level as the attack intensified. Up in the conning tower, Lucas and his executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Gordon Matheson, tried to track the enemy’s movements. The next barrage was heavier, closer. The shock waves tore through the hull like hammer blows. Something in Lucas gave way. Witnesses later described him as pale, trembling, and muttering incoherently. Matheson fared little better.

Below, Rush waited for orders that never came. The minutes stretched on. The attacks did not stop. Realizing something was wrong, he climbed the ladder to the conning tower. What he found would haunt him for the rest of his life. The helm was unmanned. Lucas and Matheson stood by, dazed and silent. There was no leadership, no direction, nothing but the throb of the pumps and the slow leak of air. Without hesitation, Rush took command. He called men to their stations, took the diving controls, and began maneuvering the boat.

The Japanese had joined forces. Two escorts now worked in tandem, taking turns attacking. Each pass brought another string of charges. The noise was deafening, the air thick with the smell of oil and sweat. Depth gauges danced wildly. Billfish was taking on water through the stern tubes, flooding the after compartments. Chief Electrician’s Mate John Rendernick arrived in the control room, his face streaked with grease and exhaustion. He reported that the leak could not be stopped, only slowed. Rush told him to do what he could. Rendernick formed a bucket brigade of men bailing by hand. Chief Engineman Charley Odom pumped grease into the tubes, slowing the inflow just enough to buy them time.

For sixteen hours the battle raged. Rush used every trick he knew. Each time a depth charge detonated, he used the noise to mask the sound of blowing ballast from the safety tanks, carefully adjusting buoyancy to keep the boat from sinking too fast. He changed depth in small increments, twisted courses, and even retraced their path beneath their own oil slick, confusing the enemy sonar. The hull groaned as pressure built. At one point the depth gauge crept below six hundred feet, far beyond the design limit. Steel screamed but held. Men prayed in silence. The air grew foul, heavy with carbon dioxide. They had no way to test its concentration, and it hardly mattered. They could do nothing but endure.

Hours blurred together. Rush’s voice was the only steady sound, issuing calm orders while others fought fatigue and panic. Each decision carried the weight of lives. Every adjustment of trim, every choice to rise or sink, could mean survival or death. At last, sometime before dawn, the explosions ceased. The enemy, convinced their prey had perished, turned away. Rush ordered the boat to rise. Slowly, painfully, Billfish surfaced into the pale morning light.

The men emerged into the humid air, gasping. They had survived what should have been impossible. Their commander, however, had not recovered. Lucas appeared on the bridge, shaken and hollow. He gave few orders and spoke little. Control of the ship remained in Rush’s hands, though the official chain of command stayed intact. Discipline demanded silence. The Navy’s code left no room for open defiance, no matter the circumstances.

Days later, a convoy appeared on the radar, five merchantmen with two escorts. It was the kind of opportunity submariners dreamed of. Rush was officer of the deck that night. Lucas came to the bridge, apparently determined to redeem himself. They went to battle stations. The range closed to ten thousand yards. At that distance, no torpedo could possibly hit. Yet Lucas turned the boat away. Rush protested. The captain said they would make another approach. They swung around, closed again, and once more Lucas ordered a retreat at the same impossible distance. Rush confronted him directly. “Captain, you can’t do this. This is wrong.” Lucas hesitated, then confessed, “I can’t do it.” Rush replied, “I can.” Lucas refused to relinquish command formally, but agreed to let Rush take the conn. The attack proceeded no further. The convoy escaped. The unspoken arrangement was clear. Lucas would finish the patrol and write the report. Rush and the crew would keep their silence.

When Billfish returned to Fremantle, the submarine looked no different from dozens of others limping in from combat. She carried no victory pennant, claimed no sinkings, and bore no visible scars. The second patrol report, filed December 24, 1943, read like a thousand others. It noted heavy depth charging and minor damage, but no casualties, no crisis, no breakdown. There was no mention of the sixteen-hour ordeal, of the captain’s collapse, or of the young lieutenant who had saved the ship. The system did not ask questions. Commanders wrote their own reports, and unless something catastrophic occurred, those reports stood unchallenged. Lucas was quietly reassigned to shore duty, then returned to command another submarine the following year. The incident vanished into silence.

Charles Rush kept his word. He said nothing. In wartime, loyalty was measured not only by obedience but by discretion. To expose a superior could destroy a career and stain the reputation of the entire service. Rush finished the war aboard Queenfish, rose through the ranks, and later worked in submarine development and staff positions. He carried the memory of that day like a sealed compartment, untouched but never forgotten.

The years after the war were kind to Frederick Lucas. He commanded surface ships with distinction, including the stores ship Graffias, the tender Shenandoah, and finally the heavy cruiser Los Angeles. His crews respected him, his record was clean, and he retired with honor in 1960. To the world, he was a successful naval officer who had served his country well. Only a few men knew that his finest hour had belonged to someone else.

Decades passed. The Cold War came and went. Submarines changed from diesel to nuclear power, from hand-turned wheels to digital consoles. The old boats were scrapped or turned into museum pieces. Their stories faded with the men who sailed them. But the sea, like history, rarely forgets. Among veterans’ circles, rumors began to surface about a patrol in which the skipper had lost his nerve and been saved by his engineer. No names were attached, no confirmation offered. It sounded like a legend, a cautionary tale whispered in bars.

By the late 1990s, with most of the participants gone and the documents declassified, fragments of the truth began to align. Former crewmen spoke to researchers. Naval historians cross-checked patrol reports. What they found did not match the official story. The evidence pointed to Billfish, to November 11, 1943, and to one man who had never sought recognition.

Charles Rush was living quietly in Port St. Lucie, Florida, retired and in his eighties. When the Naval Institute approached him for an interview, he agreed, but only to set the record straight. In that conversation, later published in Proceedings, he described the attack, the breakdown of his commanding officer, and the desperate hours that followed. He spoke with restraint, never bitter, never accusatory. He gave credit to the chiefs and crewmen who had fought beside him, saying that the ship had survived because of them. When asked why he had kept silent so long, he answered simply that a promise was a promise.

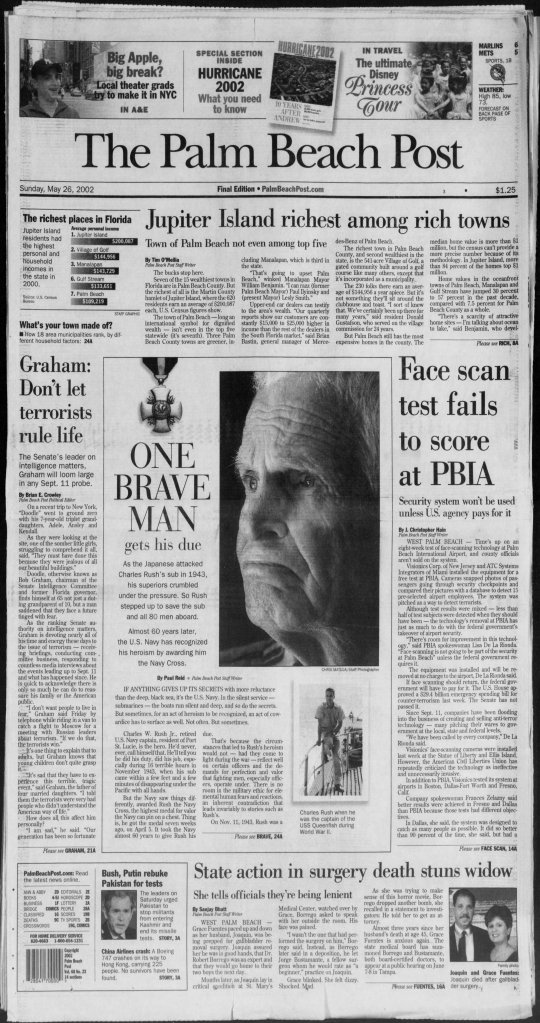

The revelations drew attention from the press and from the Navy itself. Investigators reviewed the original patrol report, crew statements, and Rush’s account. The truth was undeniable. Nearly sixty years after the attack, the Navy formally recognized his actions. On October 4, 2002, at a ceremony in Pearl Harbor’s historic Lockwood Hall, Captain Charles W. Rush Jr. was awarded the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism aboard USS Billfish.

The setting was symbolic. The Clean Sweep Bar and Skippers’ Lounge, once a sanctuary for submarine captains, held portraits of the greats: Dick O’Kane, Mush Morton, Slade Cutter, Edward Beach. Rush’s photograph joined theirs that day, unique among them as the only one not of a commanding officer. The citation read that he had taken charge when all others were incapacitated, directed damage control, and saved his ship under relentless attack. Rear Admiral John Padgett, Commander of Submarine Force Pacific Fleet, told the assembled officers that the courage Rush showed was the same spirit the service still sought to instill in its sailors. Rush, in turn, deflected the praise. “The crew of the Billfish made that submarine,” he said. “If it hadn’t been for them, there would have been no ship to save.”

The recognition came too late for most of those who had shared the ordeal. Commander Lucas had died two years earlier and lay in Arlington National Cemetery, his record unaltered. To his family and to history, he remained a respected officer who had overcome his own limitations and served honorably in later commands. The Navy did not seek to reopen questions about his conduct, nor did Rush encourage it. He had never wanted revenge, only truth.

In retrospect, the Billfish episode reveals as much about the nature of leadership as it does about war. Submarine duty in the Second World War demanded a rare combination of technical skill and emotional endurance. Officers were trained to command, but not all were built to bear the isolation and constant tension of the deep. When a captain failed, the consequences could be catastrophic. Yet the Navy’s rigid hierarchy left little room for acknowledging human limits. The system depended on the assumption that the man in charge would always rise to the occasion. When he did not, the only safeguard was the character of those below him.

That night in the Makassar Strait, the chain of command broke, but discipline did not. Rush and his crew did not mutiny. They did not abandon their captain or seek glory. They simply did what needed to be done. In that sense, their defiance was the purest form of loyalty, preserving not only their lives but the honor of the service itself. When the story finally came to light, it stood as a reminder that heroism is often quiet, anonymous, and born from necessity.

The pressure hull of a submarine is a fragile thing, designed to hold back the ocean by a thin margin of steel and nerve. When it fails, death is swift. When it holds, life continues in the narrow space between crushing depth and the will to survive. On November 11, 1943, the Billfish held because the men inside her did. They kept their heads while the world exploded around them, and in doing so, they demonstrated the essence of courage.

History often remembers the captains who led from the front, who charged into battle and returned victorious. It rarely records the moments when leadership faltered and others had to step into the void. The tale of the Billfish is one of those moments. It is not a story of triumph in the usual sense. The submarine sank no ships, claimed no kills, and earned no immediate medals. Yet it became, in time, a symbol of something deeper: the capacity of ordinary men to rise above fear and failure when everything else collapses.

When Charles Rush stood in Lockwood Hall that October day in 2002, surrounded by younger officers in crisp uniforms, he represented a generation that had seen the world at its darkest and refused to yield. His medal was not only for what he had done but for what he had endured in silence. The truth had taken six decades to surface, but it had surfaced nonetheless, like a submarine breaking through to light after too long below.

The sea keeps its secrets for a time, but not forever. The Billfish story reminds us that courage is not the absence of fear but the mastery of it, and that honor can survive even in the quiet places where no one is watching. It is a story of steel and conscience, of the weight of command and the greater weight of responsibility when command fails. The men of the Billfish proved that leadership is not conferred by rank but earned in the crucible of necessity.

The records now show that Billfish completed eight war patrols, earning seven battle stars. None of those statistics capture the meaning of her second. That patrol produced no sinkings, no glory, only survival against impossible odds. Yet it was that patrol, and the men who endured it, that gave the submarine service one of its most enduring lessons. A crew’s strength lies not only in its captain but in every man who chooses duty over despair.

In the end, that is the legacy of November 11, 1943. A captain broke, a crew endured, and a young officer named Charles Rush proved that integrity is stronger than fear. The sea closed over their wake, and for half a century the truth slept beneath it. When it finally rose again, it carried with it a quiet affirmation that even in the darkest depths, light endures.

Leave a comment