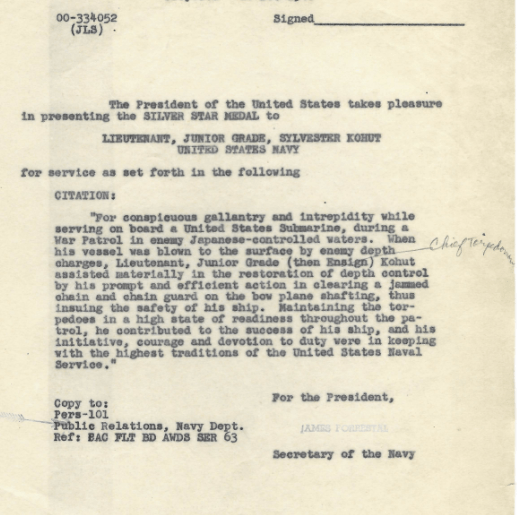

Back in early September, I stumbled on a small piece in the Standard Speaker (PA) from September 2, 1944. It was nothing more than a picture of Ensign Sylvester Kohut shaking hands with Admiral Nimitz and a line about him receiving the Silver Star. That was it. No details, no story.

It bothered me. Submarine Ensigns did not just pick up Silver Stars every day. What had he done? When? Where? And on which boat? A quick check of the USSVI WWII database had him listed not as an officer but as a Torpedoman’s Mate Chief. Something didn’t line up.

I set it aside at first, but I also sent a request to the National Personnel Records Center. Less than a month later, a copy of the citation landed in my hands. It described what Kohut had done, but still left out the crucial details. There was no mention of when or where.

That was enough to set me off digging. After working through patrol reports and ship histories, the pieces finally came together. What happened aboard USS Jack (SS-259) on June 26, 1943, during her very first patrol, was the event I had been chasing. Kohut was a plank owner on Jack, and it was his actions that day, when overconfidence nearly killed the boat, that had earned him recognition.

The official log reads cold and procedural, missing the real terror of the moment. But the hometown newspaper later captured the pride: Sylvester Kohut, now an Ensign, decorated by Nimitz himself for saving his boat in the heat of battle.

These are the stories that we must remember. TMC(SS) Kohut saved the USS Jack SS-259. He would later serve as the COB aboard USS Queenfish SS-393. His received a commission and went on to retire from the Navy. He departed on Eternal Patrol on May 22, 2001 in Las Vegas, NV., with the notation that he was a retired US Navy Sub Vet.

He was also a hero whose deeds and sacrifice must motivate us to greater accomplishments.

-ȸ

The night sea was black glass, the convoy just a set of dim silhouettes on the eastern horizon. Inside Jack, the crew carried themselves with a swagger. First patrol, first real taste of combat, and they were eager. The skipper lined them up for a clean shot. Five ships ahead, fat targets strung along like beads on a wire. Torpedoes hissed from their tubes, spread wide, and in minutes the sea erupted. Toyo Maru went down hard, then Shozán Maru. The men whispered it, they felt untouchable. Twelve torpedoes fired, two ships sunk.

The Captain stayed at periscope death to allow members of the crew to take liberty to view the ship they had hit. War, they thought, might be easy.

But that’s when the ocean turned. A straggler in the column veered toward them, setting up for a ramming run. Jack’s skipper wheeled for a desperate “down-the-throat” shot, but before they could fire, the heavens opened. A Japanese plane, unseen until it was too late, let loose an aerial depth charge. It detonated so close on Jack’s port quarter that the submarine’s stern was thrown clear out of the water. Inside the boat men were pitched against steel, gauges shattered, lights flickered. Both bow and stern planes were wrecked. Jack nosed over twenty-five degrees, sliding fast into the depths.

It was in that chaos that Chief Torpedoman Charles Kohut earned his Silver Star. With the boat headed down at a steep angle and balance gone, he threw himself into the jammed after-room, working in choking fumes and chaos. An obstructing chain guard had fouled the planes, leaving Jack unable to level. Kohut wrestled it free, restoring the ability to fight for depth control. At 380 feet, the boat finally steadied, just seconds before a steel coffin became their fate.

Jack limped clear, her radar ruined, her tubes scarred, but alive. In the silence that followed, the crew understood just how thin the line was between hunter and hunted. Overconfidence had nearly sunk them. It was not the convoy, nor the destroyers, but a single, unexpected bomb from above that almost ended Jack’s war.

It was a close call. And the lesson was burned into every man aboard: in submarines, it’s always the thing you don’t see coming that will kill you.

Leave a comment