In Ava, Missouri, Mrs. Hutchinson walked into the office of the Douglas County Herald with a request that surprised the editor. She asked them to stop sending her the papers. It wasn’t that she didn’t want to read the news, she read every line about the war as closely as any mother with a son in uniform. Her worries were different. She had been faithfully forwarding the paper to her boy, Fireman Second Class E.E. Hutchinson, serving on a submarine somewhere in the South Pacific. But letters had been few, and she had no way of knowing if the papers ever reached him. More than once, she wondered if stacks of unread issues were piling up in some forgotten postal bag while her son remained cut off from the world back home. In the end, she decided there was no sense in continuing the subscription if she couldn’t be sure he was receiving them.

It was a small gesture in a small town, but it spoke volumes about the home front reality of submarine families. Life under the sea meant silence, no word of where the boats went, no certainty of when they would return, and no way of knowing whether a package or a newspaper ever found its way aboard. Mothers and fathers, wives and sweethearts all shared the same burden: the long wait for a letter or a cable that might or might not arrive. While Mrs. Hutchinson wrestled with her decision in Missouri, her son was already underway aboard USS Sargo (SS-188).

At her helm was Lieutenant Commander Richard V. Gregory, a seasoned officer who had inherited a difficult burden. His orders were straightforward: patrol the Celebes Sea and South China Sea, watch for Japanese shipping, and attack whenever possible. The assignment was part of the Navy’s broader strategy—strangling Japan’s supply lines, cutting into the flow of oil, ore, rice, and rubber that fed the enemy’s war machine.

Fremantle, meanwhile, had become one of the submarine force’s busiest bases. The city offered a warm welcome, but for the men of Sargo, liberty was already fading into memory. They knew the long weeks ahead would be filled with the monotony of patrols, the anxiety of equipment failures, and the constant threat of enemy patrol craft. For the crew, Fremantle was just another dot to mark in the log before the real work began.

And that work was made harder by the unreliable weapons they carried. The Mark 14 torpedo was still plagued with flaws—premature explosions, duds, and the dreaded circular runs that could turn a submarine’s own shot back against her. Gregory and his officers could not trust the torpedoes they fired, but they had no alternative. Every patrol was a wager against bad luck, with the crew’s lives staked on whether the Navy’s ordnance would work as designed.

As Sargo pushed north, the men settled into the rhythm of a patrol. Each dawn meant a dive to check trim and clear the horizon. Each dusk brought a return to the surface for air and speed. Lookouts stood their lonely vigils topside, scanning for smoke or masts. Below decks, sailors drilled, repaired balky valves, and tried to keep the engines humming. Even so, by the first week out of Fremantle, Sargo’s patrol report was already recording trouble: No. 3 main engine exhaust valve leaking so badly the drain pump could hardly keep up. Problems like that could cripple a boat if they happened at the wrong time.

From Ava, Mrs. Hutchinson could not know the particulars. She only knew that her son was “out there.” She didn’t know about Lombok Strait, about trim dives or leaky valves. She didn’t know that submariners often spent more time waiting than fighting. She only knew she wanted her boy to keep up with the news of home, to feel connected to the town and family he had left behind. Whether those papers ever made it into his hands is uncertain. What is certain is that her concern was not about bad news in the headlines, but about the silence that stretched between a mother and her son beneath the sea.

For the crew of Sargo, the silence was their constant companion. No news from home, no certainty from headquarters, only the vast Pacific and the enemy convoys that might or might not appear. As the calendar turned from August to September, the submarine pressed on into dangerous waters, one of many boats trying to choke Japan’s lifeline. And in Missouri, Mrs. Hutchinson rose each morning to a house without the Herald on her porch, clinging to faith that her son was safe and perhaps, somewhere under the sea, reading a letter or a newspaper she had sent weeks before…

On the night of 27 August 1942, Sargo slipped her moorings in Fremantle and began her long run north. The patrol report doesn’t waste words: “Underway from alongside USS Trinity, Fremantle harbor… six officers, sixty-seven men, twenty torpedoes, fuel, water, lubricating oil, and stores to capacity on board.” It was the kind of entry that captured nothing of the emotions of departure. For the crew, though, the moment carried weight. Ahead lay weeks of tension, danger, and silence. Behind them, the fading lights of Fremantle, the last safe harbor they would see for nearly two months.

At the periscope shears, Lieutenant Commander Gregory knew exactly what was expected of him. Commander Submarine Squadron 21 had issued Operation Order 80-42: proceed through Lombok Strait into the Celebes Sea, then push into the South China Sea. The goal was the same as it had been for every boat since the war began—find and sink Japanese shipping. Oil tankers from Borneo, rice from Indochina, ore and rubber from the Indies: the lifeblood of the Japanese war machine flowed along those sea lanes. Submarines like Sargo were ordered to cut them.

Orders were clean on paper, but messy in practice. The routes were guesses based on scattered intelligence, submarine sightings, and the reports of coastwatchers. Convoys could shift routes at a whim. Weather could scatter them or conceal them. Gregory’s job was to gamble his boat into the right position, to sit patiently and wait, and then to strike with a weapon he couldn’t entirely trust.

That weapon was the Mark 14 torpedo. The Bureau of Ordnance insisted it was flawless, but every skipper in the Pacific knew better. Duds, premature explosions, and the nightmare of circular runs were fresh in memory. Gregory had already seen enough on earlier patrols to know that the biggest enemy he faced might be the steel tubes stored in his own forward room. Yet he had no choice but to carry them. The 20 torpedoes aboard represented his only real striking power. The deck gun was a fallback, not a primary weapon.

The crew settled into the rhythms of patrol almost immediately. At dawn on the 28th they made a trim dive, checking valves and hatches. At 1406 they sighted a PBY patrol plane, friendly, and at 2000 that night the boat’s position was logged at 29°31’S, 113°35’E. The war diary notes “fuel used 4205 gallons” as if that mattered more than the nerves of sixty-seven men locked in steel.

Exhaust valves continued to be a problem. No. 3 engine exhaust valve leaked badly, faster than the drain pump could keep up. On September 1, both No. 3 and No. 4 exhaust valves leaked faster than the pumps could handle, forcing an early surface. Such problems dogged every submarine, but in narrow waters like Lombok Strait, a forced surface could mean death. Men worked around the clock to keep the engines in fighting trim, knowing they might fail at the worst possible moment.

On September 3, Sargo entered Lombok Strait, one of the narrow gateways into the northern seas. At 0300, the boat sighted the tips of masts and began an approach before realizing the target was nothing more than a sailing vessel. Later, they sighted the submarine USS Salmon also moving through the strait, a brief reminder that while each boat patrolled alone, they were part of a larger fleet effort spread thin across thousands of miles of ocean.

By early September, Sargo had reached the Celebes Sea. Gregory’s plan was to work eastward choke points and shipping lanes, probing around Balikpapan and the Makassar Strait, where Japanese tankers and freighters were expected. The patrol report is filled with terse observations: “sighted tips of two masts and commenced approach… identified as small sailing vessel.” “Sighted Sekana Island.” “Dove at dawn, surfaced at dusk.” Long days of nothing but soundings, course changes, and the hum of machinery.

This was the life of a submarine patrol. Days and weeks of monotony, punctuated by a few minutes of sheer terror or triumph when an enemy ship finally appeared on the horizon. For Gregory and his crew, those minutes had not yet come. But they were drawing closer to the waters off French Indochina, where shipping traffic was heavy and the odds of contact increased.

When Sargo cleared Lombok Strait and headed north into deeper waters, the men knew they were leaving the relative safety of familiar waters behind. Now they were in the enemy’s backyard, in lanes patrolled by aircraft and destroyers, close to the shipping that kept Japan fighting. Gregory’s orders were clear: close with the enemy, attack, and sink ships. The rest was up to the skill of his officers, the endurance of his crew, and the luck of the sea.

And so, the boat pressed northward, her daily log recording bearings and gallons of fuel while her men carried the weight of silence. In Missouri, a mother folded her hands at night, unsure if her son was even receiving the hometown news she sent. In the South Pacific, her son bent over gauges in a cramped engine room, sweat dripping, every dive and every surfacing bringing them one step closer to contact…

The first weeks of September passed slowly for Sargo. The patrol report makes the days look routine: trim dives at dawn, surfacing at dusk, soundings, bearings, and fuel logs. Yet behind the sterile entries was the tension of a crew waiting for the war to break into their lives. They knew what the orders said. They were to patrol the Celebes Sea, move into the Makassar Strait, and cut across Japanese shipping lanes. Somewhere out there, merchantmen were moving oil and ore, escorted by destroyers ready to kill any submarine that showed itself. Every dawn dive was a prayer that this would not be the morning an aircraft caught them on the surface.

On 3 September, a small excitement came in Lombok Strait. At 0300, lookouts spotted the tips of two masts. The crew rushed to stations and began an approach. The night was tense, the men hoping for a target worthy of their torpedoes. Through the periscope the outlines grew clearer, and with a sinking feeling the skipper realized the truth. It was no freighter, no oiler. Just a small sailing vessel, hardly worth a 21-inch torpedo. The men stood down. A short while later, Sargo sighted the masts of another submarine, identified as USS Salmon, moving through the strait. A reminder that they were not entirely alone, though they operated as if they were.

The next days followed in monotony. From 5 to 9 September, the boat cruised the Celebes Sea, diving each morning, surfacing each night. No enemy ships appeared. The log records “trim dive at 0610,” “surfaced at 1830,” and little more. Men read dog-eared magazines, played cribbage, and sweated at their posts. The air inside the boat grew heavy and stale. Each time the boat surfaced, the rush of fresh air felt like a gift.

From 10 to 15 September, the patrol reached the approaches to Makassar Strait. Here the tension grew. These were choke points, narrow waters where shipping had to funnel. Escorts were thick, and the men expected contact at any moment. On the 11th, Gregory noted sighting smoke on the horizon, likely a convoy. An approach was begun, but the angle closed poorly, and the chance slipped away. On the 12th, another sighting led to an attempted intercept, but escorts forced Sargo down before she could fire. By the 14th, Gregory admitted in his report that these approaches had been “badly handled.” It was a rare candid note from a commanding officer. It meant missed opportunities, wasted days, and the gnawing frustration that they were out here risking everything and had nothing to show for it.

The crew felt that frustration too. For a submarine sailor, the hardest part of a patrol was not the attacks but the long stretches of nothing. Men trained to fight sat in silence, waiting for something to break the monotony. They were ready to strike, yet day after day the horizon remained empty. Some wondered if the shipping lanes had shifted. Others muttered about bad luck. The truth was more complicated. Convoys were unpredictable, and intelligence was thin. A submarine could be in the right place but at the wrong time, missing the enemy by hours.

From 16 to 22 September, Sargo pressed on into the South China Sea. Heavy weather rolled across the waters, hampering visibility. The patrol report speaks of “few sightings” and “no valid contacts.” Gregory kept to the pattern: dive at dawn, surface at dusk, search the horizon. Fuel figures and course headings filled the pages, but not the drama the men longed for. Below decks, engineers continued to wrestle with balky exhaust valves. Number 3 and Number 4 engines still leaked badly, forcing constant attention. Men in the engine room stripped to the waist, drenched in sweat, trying to keep the machinery alive.

Even without enemy contact, the strain wore on the crew. Every submerged day drained the batteries. Every surfacing risked discovery. The men knew that if they blundered into a destroyer, it could all be over in minutes. That knowledge rode with them into their bunks at night, into the wardroom where officers studied charts, into the control room where men hunched over gauges. A patrol was as much endurance as combat.

By the third week of September, frustration had begun to edge into worry. They had patrolled the Celebes Sea, tested the Makassar Strait, and slipped into the South China Sea. Yet they had not fired a single torpedo. Each day burned fuel and food. Each day carried them deeper into enemy waters. Gregory needed a contact, something to justify the patrol, something to strike back at the enemy who seemed to slip from their grasp.

That silence would not last. On the morning of 25 September 1942, off the coast of French Indochina, smoke on the horizon would finally resolve into the shape of a Japanese freighter. The long monotony of the patrol would snap into sudden violence, and Sargo’s crew would learn firsthand what it meant when a torpedo betrayed the very boat that fired it…

The morning began like any other. Sargo had slipped beneath the surface at dawn, her crew resigned to another day of routine watch standing, stale air, and silence. The South China Sea stretched empty in all directions. At 1025 hours, the monotony ended. Lookouts peering through the periscope sighted smoke on the horizon. Slowly, the gray outline of a freighter grew into view. This was the moment they had been waiting for since Fremantle.

Through the lens, the target resolved into a Japanese merchantman, later identified as TEIBO MARU, a 5,400-ton freighter once known in peacetime as the Nordbo. She steamed along the shipping route off French Indochina, near Cap St. Jacques, oblivious to the steel predator sliding into position below the waves. For Gregory and his men, the hunt was on.

Battle stations were sounded. Men rushed to their posts, hands steady but hearts racing. The torpedo data computer clattered as bearings were fed in. Gregory maneuvered the boat into firing position, periscope rising briefly above the waves to check angle on the bow and range. At 1122 hours, satisfied with his solution, he gave the order to fire. Tubes hissed and the deadly “fish” sped toward the freighter.

Seconds ticked by. Men strained to hear the rumble of an explosion through the hull. Nothing came. Instead, a terrifying cry rang out from the torpedo room: “Circular runner!” One of the torpedoes had failed in the most dangerous way possible. Instead of running straight for the target, it curved back toward the submarine that had launched it.

Every man aboard knew what that meant. A Mark 14 coming back could sink them as surely as an enemy destroyer. The control room exploded into action. Orders barked, planes shifted, rudder thrown hard over. Sargo heeled as she clawed away from her own weapon. The seconds dragged into eternity. Somewhere out in the sea, the faulty torpedo ran its doomed circle until it sank or detonated harmlessly. Below, men held their breath, waiting for the shudder of their own destruction. It never came. They had escaped, but just barely.

The other torpedoes had done their work. Through the periscope, Gregory saw the freighter stagger. She had been hit, but she was not sinking. TEIBO MARU settled in the water, wounded but afloat. Smoke drifted from her decks, and her crew began to scramble in confusion. The sea around her churned, but she remained stubbornly alive.

Gregory faced a decision. He could break off and leave her crippled, but in enemy waters a damaged ship could be towed and saved. His orders were clear: sink the target. And so he chose the risky path. At 1210 hours, Sargo surfaced to finish the job with her deck gun.

The submarine broke the surface, hatches opening, men scrambling to stations. The 3-inch gun crew swung their weapon into place. Shells were manhandled up, breech slammed shut, and the first round roared out. The freighter’s hull rang with impact. More shots followed. Men cheered as they saw splashes tear into the superstructure. Smoke thickened, flames spread, and TEIBO MARU’s back finally broke under the pounding. Within minutes she was sinking, her crew abandoning ship into the sea.

The patrol report records it with grim understatement: “Enemy vessel sunk by gunfire, estimated 5,400 tons.” For the men who had endured weeks of nothing, it was vindication. Their patrol now had a victory. One less freighter would carry supplies to Japan. One more name would appear on the long list of Japanese merchant losses.

But celebration was short-lived. The gun action had been noisy, the smoke visible for miles. Within hours, Japanese escorts were hunting the waters around Cap St. Jacques. What had begun as a triumph turned into one of the most grueling ordeals of Sargo’s career.

For the crew, the attack was a rollercoaster of emotions. The thrill of sighting the target, the terror of a circular torpedo nearly killing them, the satisfaction of sinking a freighter, and then the dread of being hunted. It was the submarine war in microcosm, all in a single day.

TEIBO MARU’s loss mattered. Japanese records later confirmed that she went down that day, exactly where Gregory reported the attack. The circular runner highlighted again the chronic failure of the Mark 14 torpedo, a weapon as dangerous to its own crews as to the enemy. Gregory had shown both aggression and caution, pressing his attack despite the danger, then improvising with gunfire when torpedoes failed to finish the job. It was the kind of leadership that kept the submarine force in the fight during the lean years of 1942.

The freighter had gone down, but in the submarine war a sinking was often just the beginning of trouble. When Sargo finished off TEIBO MARU with gunfire on the afternoon of 25 September, the smoke of the burning ship drifted for miles. The thunder of the deck gun echoed across the water. Japanese eyes and ears were not far away.

By evening the sound of screws reached the hydrophones. Gregory ordered Sargo deep. Within the hour the first charges rolled into the sea. The calm of victory was shattered by the violence of explosions hammering through the hull. Metal groaned. Light bulbs flickered. Paint chips rained down from the overhead. The boat lurched as water forced against her hull.

The next twenty-two hours were some of the most punishing of the patrol. The Japanese escorts circled and attacked with grim persistence. The submarine was forced to stay down well beyond the safe endurance of her batteries. Air grew hot and stale. Sweat dripped down faces and soaked into clothes. Men worked in silence, listening to the destroyers above. Each time the sound of screws grew louder, men braced themselves for another barrage.

Depth charges fell in patterns, some close, some farther off. The ones that landed nearby were unforgettable. The entire boat jumped as if struck by a giant’s fist. Dials wavered. The sound of metal shrieking filled the control room. A near hit could buckle a plate or rupture a joint. Every man aboard knew the boat could be their coffin if luck failed.

Gregory kept his crew steady. He ordered the boat down to safe limits of depth, nursing her along as quietly as possible. Maneuvers were minimal. The fewer noises they made, the better the chance the Japanese would lose contact. Each change of depth risked giving away their position, yet staying still invited another guess from the escorts. It was a deadly chess game played in three dimensions, blind to everything but the sonar pings above.

The patrol report captures the ordeal with a few sparse lines: “Remained submerged twenty-two hours under prolonged depth charge attack. Batteries dangerously low.” What it does not record is the strain on the men. In the torpedo room sailors lay on the deck with their heads against the steel, trying to gauge the distance of explosions. In the control room eyes flicked between gauges, watching the battery meter creep downward. In the engine room, men prayed the seals would hold against the mounting pressure.

As the hours dragged into the night, the air inside the boat turned foul. Carbon dioxide scrubbers strained to keep up. Cigarettes were unlit, meals uneaten. Every man’s stomach tightened with the expectation that the next charge could be the last. The submarine force had a saying: there were no atheists at test depth. That night aboard Sargo, prayers mixed with sweat in the stale air.

Some charges were so close the hull rang like a struck bell. After each series, the men waited for flooding to begin. But the compartments stayed dry. Rivets held. The hull kept its shape. Sargo had been lucky, and well-built.

By dawn of the 26th the Japanese escorts were still hunting. Men were exhausted, their nerves stretched thin. Battery readings dipped dangerously. The boat could not remain submerged much longer without suffocating or losing all power. Gregory had to gamble that the destroyers had lost contact. Slowly he eased the boat shallower, listening for screws. Finally, when the hydrophones reported only distant sounds, Sargo surfaced under cover of darkness to recharge batteries. Fresh air rushed into the boat. Men staggered to the deck to breathe it in, their faces pale from the ordeal.

They had survived twenty-two hours beneath the sea, hunted and hammered but not broken. The boat bore scars, but none that crippled her. The crew had been tested, and though tired and shaken, they had held together. Gregory noted only the facts in his report. For the men, the memory of those hours would stay long after the patrol was over.

When the last depth charges faded and the sea grew quiet again, Gregory turned Sargo back to her patrol. There were still weeks left before they could return to Fremantle. There were still torpedoes in the tubes and fuel in the tanks. The Japanese had tried to kill them and failed. Now it was time to slip back into the shadows and hunt again.

The ordeal off Cap St. Jacques had taken its toll, but Sargo still had a patrol to finish. After twenty-two hours beneath the sea, hammered by depth charges and running on exhausted batteries, Gregory surfaced under cover of night and put his boat back on station. The air was sweet, the stars brilliant, but the men were worn thin. There was no time to linger. Headquarters had ordered them to cover shipping lanes in the South China Sea, and Gregory intended to finish his assignment.

Through the end of September, the patrol continued in the same pattern: dive at dawn, surface at dusk, hunt by periscope and sonar. The men moved with the weight of fatigue on their shoulders. Food was running low, the bread stale, the coffee bitter. Each day was a test of patience. The freighter they had sunk was a victory, but it was a long patrol to bring home for a single kill.

On several occasions the crew caught glimpses of smoke on the horizon. Each time hopes rose that another target had wandered into their sights. But, more often than not, it was a neutral or a small craft not worth the risk of a torpedo. On one day the boat closed for an approach, only to discover the “merchantman” was a coastal sail boat. On another, the periscope revealed a convoy guarded by destroyers too alert to allow an attack. Gregory weighed his options and declined to press, unwilling to waste torpedoes or expose his crew to another chase without a clear chance of success.

Mechanical troubles never seemed far away. Exhaust valves continued to leak, just as they had since leaving Fremantle. On more than one dive, the engine room reported water pouring in faster than the drain pumps could handle. Each time the crew scrambled to keep the problem under control. Worse still, one of the main engine clutches slipped under load, threatening to cripple their ability to maneuver on the surface. These issues would haunt the boat until her return, reminders that the submarines of 1942 were fighting as much against their own machinery as the enemy.

The sea itself added to the trial. In October heavy weather rolled across the South China Sea. Rain lashed the bridge, waves pounded the hull, and men on lookout clung to lifelines while green water broke over the deck. Below, the boat lurched and rolled, dishes clattering, men bruised by sudden shifts. It was a miserable existence, one that wore at morale as much as the lack of action.

Gregory’s patrol report during these days grows sparse, a reflection of the emptiness of the hunt. “Surfaced at 1830. Dove at 0610.” “Sighted unidentified mast. Lost contact.” “No enemy ships sighted.” The kind of lines that filled page after page, giving no sense of the weeks slipping by. For the men, those lines meant endless drills, endless waiting, and endless wondering if their luck would hold until they were ordered home.

Finally, in the third week of October, Gregory received orders to head back to Fremantle. Fuel and provisions were running thin, and the patrol had yielded all it was likely to. The crew welcomed the turn south, though they knew it meant another thousand miles of danger before they saw port. Japanese aircraft prowled the seas, destroyers guarded choke points, and mines waited in straits. Every mile home had to be earned.

The return voyage brought no more combat, only the steady grind of navigation and endurance. Lombok Strait loomed again, the same narrow passage that had carried them north. On the night run through, lookouts strained their eyes against the blackness. The boat slipped through without incident, though the tension was high until they were clear.

On 25 October 1942, after fifty-nine days at sea, Sargo slid back into Fremantle harbor. The war patrol was over. The patrol report closed its final entry with a simple notation: “Patrol terminated.” The results were modest on paper. One freighter sunk, 5,400 tons destroyed. Yet the story behind those figures was much greater.

The men had endured two months of silence and monotony; of mechanical failures and stale air. They had survived a circular running torpedo that nearly killed them, and twenty-two hours under relentless depth charge attack. They had fought their enemy with weapons that betrayed them and still found a way to win. They had come back alive, which in the submarine service of 1942 was a victory all its own.

For Gregory and his officers, the fifth patrol was not the most successful in tonnage, but it proved the resilience of their crew and the sturdiness of their boat. Every submarine commander knew the war was a long campaign, and sometimes survival was achievement enough. The sinking of TEIBO MARU stood as proof that even with faulty weapons and relentless opposition, the submarines of the Pacific Fleet could still strike.

The war patrol was complete, and Sargo would sail again. For the families waiting back home, the silence would continue. For the men aboard, the next set of orders was already being drawn up. The fifth patrol of USS Sargo was just one chapter in a long war, but for the men who lived it, and for the families who waited, it was everything.

Epilogue – The Papers Did Arrive

The silence that weighed on Mrs. Hutchinson eventually lifted. The Douglas County Herald printed a short notice in November 1942 that Fireman Second Class E. E. Hutchinson was indeed receiving the newspapers his mother sent. Far from being lost in some forgotten mailbag, they had reached him aboard his submarine, and he was “very happy about it.”

That small line in a small-town paper carried a meaning greater than tonnage figures or patrol reports. It was proof that across thousands of miles, through Navy mail clerks, transport ships, and the hazards of war, a mother’s determination to keep her son connected to home had succeeded. While he stood watch in the heat of the engine room or listened to the roar of depth charges in the control room, he could still unfold a copy of the Herald and glimpse the world he had left behind.

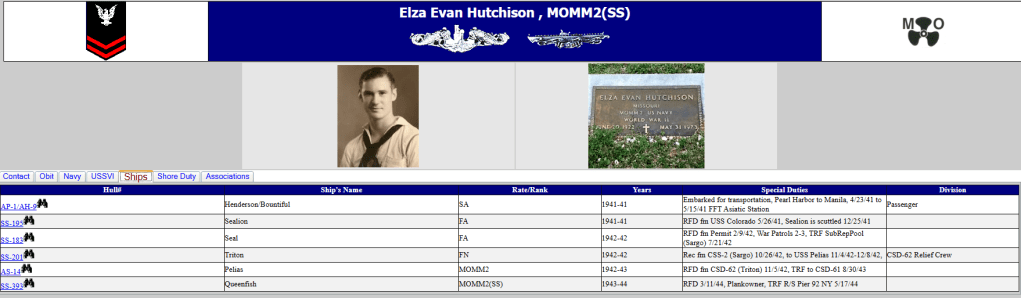

E. E. Hutchinson survived the war. He came home to Missouri, carried on with life, and bore the same quiet dignity that defined so many of his generation. Three decades later, on 31 May 1973, he departed on eternal patrol.

For the men of Sargo’s Fifth War Patrol, the record shows one freighter sunk and 5,400 tons destroyed. For a mother in Missouri, the record shows something far more important: her son got the papers, he read them, and he was glad to know his family had not forgotten him.

Leave a comment