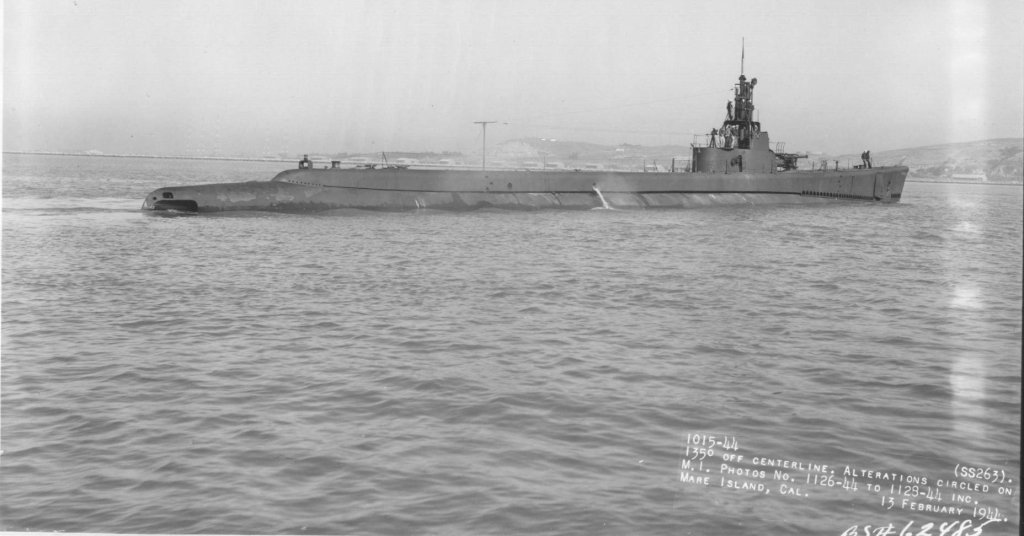

The first days of September 1944 found the USS Paddle deep in enemy waters, sliding along the edge of the Sulu Sea and the Celebes, that broad, restless stretch of ocean where islands rise like jagged teeth out of the water. She was a Gato-class submarine, crewed by men who had already seen enough of the war to know its rhythms. They knew the false alarms, the sudden bursts of action, and the endless stretches of waiting. For them, the days blended into a pattern of diving before dawn, running silent through the daylight hours, then surfacing at night to breathe, to charge the batteries, and to prowl.

The crew had no illusions about where they were. These seas were patrolled heavily by Japanese planes and prowling escorts. By this point in the war the enemy knew that American submarines were everywhere, and the Japanese were better at hunting them than they had been two years earlier. Every periscope raised, every radar sweep was a gamble. It could reveal a fat freighter on the horizon, or it could reveal a plane banking down to drop depth charges or a destroyer with its guns already pointed.

The men aboard Paddle were young, most in their early twenties, hardened by the cramped life of a submarine. They slept in shifts, hot-bunking in the narrow confines, air always tinged with the smell of oil and sweat. Conversations were quick, sharp, filled with that gallows humor sailors lean on when the next day might be your last. They thought about the mechanics of war: the radar contacts, the range and bearing, the reliability of the torpedoes. That was their world.

What they did not know, what they could not know, was that somewhere ahead of them sailed a Japanese freighter with a name they had never heard, Shinyo Maru. To their eyes it would be just another target in a war that demanded more and more tonnage sent to the bottom. To the men locked in her holds, it was hell itself. They were Americans too, prisoners who had been through Bataan, Corregidor, the Death March, the camps, men who had endured starvation and abuse for more than two years. Seven hundred and fifty of them crammed below decks, beaten, denied air, and left to swelter in the heat.

But Paddle’s crew did not know that. On September 1, 1944, all they knew was that they were beginning another week of patrol in waters where danger might appear at any moment, and where the line between success and tragedy was thinner than the skin of their boat.

The log for September 1 was as uneventful as a submarine patrol could be. The crew ran on the surface through the night, scanning the dark horizon, waiting for a radar return that never came. The message board in the control room carried word of a change in patrol orders, pushing Paddle south toward the Sulus, where the Navy believed Japanese traffic was still moving supplies and fuel between the islands. Orders were orders. The crew grumbled about it over coffee and tinned fruit, but they turned their bow as told. The ocean didn’t much care what their assignment was.

The next day, September 2, the tension ratcheted up. At dawn a periscope watch caught a flash of gray in the rain squalls—a small Japanese torpedo boat. For a moment hearts jumped. Was it part of an escort screen? Was there a convoy behind it? But the little boat was alone, ranging back and forth, sonar pings echoing across the water. Not worth a torpedo, too dangerous to gun. They let it go, sliding beneath the waves and biding their time. Later, a blip on the radar told of an aircraft closing in. The boat went deep again, silent, men lying still in their bunks, listening to the faint hum of propellers far above. Nothing fell from the sky that time, but it was a reminder of how closely they were being watched.

September 3 began with the transit of Balabac Passage, narrow water, the kind of place every submariner hates. Too close to land, too easy to trap. Again, Japanese planes forced them down, once at ten miles, then again when another came in at eight. The VHF antenna had cracked, leaving the men to jury-rig a fix. Every system mattered, every wire and insulator, and nothing could be replaced until they limped back to Fremantle. They made do. They always did.

By September 4 they were lining up for Sibutu Passage. Too much moonlight, too many chances to be seen. The boat hugged the shadows, and even so a fast craft came tearing across the bow like a phantom. For an instant it seemed collision was certain, then the Japanese boat vanished into the night. Nobody slept well after that. The tension sat in every man’s stomach like a stone.

The 5th was stranger still. Floating debris drifted by the periscope, the kind of sight that might mean a wreck, or might mean nothing more than storm-flung trees. For a few minutes they thought they saw a mast—perhaps a small escort. They hunted for it, searched at periscope depth, then surfaced and looked again. Nothing. A floating coconut tree, maybe. Or maybe something else. You could never know for sure in those waters. That night they made what they thought was an approach on a large freighter with an escort, moonlight glinting on the horizon, the silhouette unmistakable. Only when they crept close did they realize it wasn’t a ship at all, but Sangboy Island itself. Out here, even islands could play tricks on your eyes.

On September 6 the monotony was broken again by aircraft, this time circling along the Mindanao coast. By now the crew knew it was routine, a standing patrol meant to keep American subs from hugging too close to the land. Every time Paddle’s gray hull slipped beneath that clear tropical water, there was a chance it would be spotted. The paint was flaking, the camouflage imperfect, and the Japanese patrols were sharp. At one point a fishing boat appeared on the horizon. Even that had to be treated as a threat. They turned away, watching, waiting until it was gone.

That night, just when the men thought the day was done, the number one main engine quit again. The same problem as before—a sheared shaft on the oil pump drive. It was the third time that had happened on this patrol. For forty hours, one quarter of their main power was dead, leaving them slower to dive, slower to maneuver. Submariners knew how thin their edge of survival was, and losing power made it thinner still.

So the first week of September dragged on, a mixture of false alarms, mechanical headaches, and the constant feeling of being hunted. The crew of Paddle had no victories to show for it, no tonnage sunk, only more gray hairs and frayed nerves. Yet they stayed at it, because somewhere ahead there had to be real targets. Somewhere, there had to be Japanese ships to sink. What they could not imagine was that the week of waiting was leading them directly toward one of the cruelest intersections of fate in the entire Pacific War.

On the morning of September 7, 1944, the ocean finally delivered. Off the tip of Sindangan Point, smoke rose on the horizon. Then the sharp eyes on periscope watch picked out masts and stacks, and soon enough the outlines of ships took shape against the green hills of Mindanao. At last, a convoy.

The formation was textbook Japanese: a medium tanker in the lead, close to the coastline, followed by two medium freighters and a pair of smaller ones, with at least two escorts prowling back and forth on station. Overhead circled floatplanes, buzzing like hornets. To the side lumbered a squat coastal tanker, odd-looking, with its ungainly masts sticking high. Off on the flank, almost too far to make out, lurked another vessel that looked suspiciously like a Q-ship, one of those disguised freighters rigged with hidden guns. To the men of Paddle, this was the kind of target group they had been sent halfway around the world to find.

The tension in the control room spiked. Orders came fast, precise, clipped. Helm adjusted course, diving planes tilted, the torpedo data computer hummed as bearings and ranges were fed in. Each man at his station knew the drill, knew that the next few minutes would decide whether the patrol was a success or a failure.

What no one aboard knew—what no one could know—was that in the center of that convoy steamed a vessel named Shinyo Maru. To Paddle it looked like any other Japanese cargo ship, another Maru hauling fuel or materiel. In truth, below her decks were seven hundred and fifty American prisoners of war. They were men who had survived the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, the Death March, the prison camps of Luzon, the starvation and beatings and disease. They had endured for more than two years, only to be herded now into the black iron belly of a freighter with no markings to show the world who they were.

The firing solution locked in. At 1637 hours, four torpedoes roared out toward the leading tanker. Two struck, throwing columns of water and fire into the air. The Japanese convoy erupted in confusion, escorts breaking formation, planes swooping lower. In the chaos, Paddle shifted aim and fired again, this time at the cargo ship following behind. Two more torpedoes ran straight and true. The submarine went deep immediately, the hull groaning as she descended, every man aboard waiting for the counterattack.

It came hard and fast. Depth charges rolled into the sea, forty-five of them, hammering the water above, shaking the boat like a toy. Lights flickered, gauges rattled, men held their breath and stared at one another in the dim red glow. They heard the sound every submariner longed for: the hollow, wrenching boom of a ship breaking apart, bulkheads giving way, steel tearing in two. To them it meant another Japanese freighter gone, another enemy cargo lost to the depths.

They could not see what was happening on the surface. They did not hear the panic as hatches were thrown open on Shinyo Maru, or the screams of the prisoners as Japanese guards turned their rifles and machine guns on men scrambling for freedom. They did not see the few who managed to dive into the sea, or the many who never even made it out of the hold. All the crew of Paddle knew was that their torpedoes had struck home, and that the enemy had paid.

The boat rode out the barrage, silent and steady, listening to the echoes of destruction above. When the last charges fell and the waters calmed, the crew slowly exhaled, trading weary grins, convinced they had done their part in strangling Japan’s supply lines. None of them could guess the truth—that in sinking one enemy freighter, they had also taken down hundreds of their own countrymen.

While Paddle slid into attack position, unseen in the green waters off Mindanao, the men in the dark belly of Shinyo Maru lived a very different kind of waiting. Seven hundred and fifty prisoners of war were crammed into the ship’s hold, a space meant for cargo, not men. They had been shoved below decks days earlier, packed shoulder to shoulder with almost no room to move. The air was foul, a mix of sweat, urine, and rust, and men fainted in the heat. Buckets served as latrines, and there was never enough water. The Japanese guards kept the hatches closed, leaving only a trickle of light and air.

These were men who had already endured too much. They had marched through Bataan in the blazing sun, watched comrades bayoneted or shot for falling behind, wasted away in prison camps where rice gruel was a luxury and disease stalked every corner. By 1944, they were skeletons wrapped in skin, still clinging to the hope that somehow they would live long enough to be freed. When word spread that they were being shipped north, many thought it might mean the end of captivity, maybe a transfer to Japan itself. They could not know the Japanese had no intention of treating them as anything more than disposable cargo.

Survivors later described how time blurred in the hold. They counted breaths, listened to one another cough, whispered prayers. The heat was suffocating. At night men would pass out, and in the morning they would not wake. The guards above sometimes tossed down a ladle of water, sometimes not. They laughed, smoked, and played cards while the prisoners lay in the dark.

On September 7, when Paddle’s torpedoes slammed into the convoy, the prisoners knew it instantly. The ship lurched, iron screamed, men were thrown against one another. For a brief moment, hope flared—American submarines were out there, fighting, striking back. Some shouted that rescue had come. But then the hatches above were flung open, and Japanese guards began firing into the hold. Machine-gun bursts tore into the packed prisoners, and panic turned to horror. Those who could ran for the ladders, some leaping into the sea through blasted holes in the hull, others cut down before they reached the deck.

In the chaos, a few managed to escape into the water. Most never had the chance. Guards fired into the waves at struggling figures. Survivors remembered clinging to wreckage, trying to stay under until the patrol boats passed. Out of 750 men, only 82 would survive. The rest, after years of suffering, died in minutes—either trapped in the sinking ship, shot by their captors, or drowned.

None of this was known to the men aboard Paddle. In the control room, they were listening to depth charges and the faint echoes of a ship breaking apart. To them, it was victory. To the men below decks of Shinyo Maru, it was massacre.

The next day dawned like any other patrol day. Paddle surfaced, the sun rising over the Mindanao coast, and the crew shook off the previous day’s tension. They had survived the depth charging, they had heard the sounds of ships breaking up, and to them that meant success. The war patrol report would record it in the clean, spare language of the Navy: a convoy attacked, a tanker damaged, a freighter sunk. For the men aboard, it was another notch in the tally of victories that would help strangle Japan’s supply lines.

On September 8, no new targets appeared. Patrol continued, the men keeping their usual routines—some playing cards in the cramped mess, others catching what little sleep they could in the hot bunks. Mechanical issues with the engines continued to dog them, and every surfacing meant a lookout for enemy planes. On the 9th, another ship was engaged and sunk, this time without the confusion of escorts or aircraft. It was a cleaner attack, and one they could watch go down. By then the Shinyo Maru was already resting on the bottom, her story hidden beneath the waves.

When Paddle completed her patrol later that month and returned to port, she carried no sense of tragedy. The crew believed they had struck a blow at Japanese shipping, nothing more, nothing less. The war ground on, and there was no time for reflection. It would be months before the United States learned the truth, and years before survivors’ accounts painted the full picture of what had happened that day off Sindangan Point.

Only after the war did the men of Paddle hear the bitter irony of their success. The ship they had torpedoed was not only an enemy freighter, but also a hell ship packed with Allied prisoners. They had been forced to endure captivity, starvation, and beatings, only to be drowned or gunned down by their captors when rescue seemed near. Out of 750 aboard, just 82 men lived to tell the tale.

Historians later called it one of the darkest tragedies of the submarine campaign, though they were careful to point out that the crew of Paddle could not possibly have known. The Shinyo Maru carried no markings, no Red Cross, nothing to distinguish her from any other Japanese cargo vessel. American intelligence had intercepted radio traffic that hinted at the presence of prisoners, but by the time that information was filtered down to submarine commanders, those details had been stripped away. Commanders were told ship names, tonnage, escorts—not what cargo they carried. The men who pulled the triggers in Paddle’s torpedo room did exactly what they were trained and ordered to do.

For the crew, the news years later must have been a gut punch. What had seemed like triumph had carried a shadow they never could have guessed. The Navy did not blame them, but history did not let the irony go. Victory and tragedy had been wrapped together in a single salvo of torpedoes, and no one aboard Paddle knew it until long after the war was won.

Looking back across the years, the events of early September 1944 are hard to place neatly into the ledger of war. The men of Paddle were doing their jobs, carrying out orders with precision and courage, hunting enemy shipping in dangerous waters. Their attack was by every measure a success. A tanker crippled, a freighter destroyed, the convoy scattered. They had risked their lives under depth charge and air patrol, and they had come through it. By the cold arithmetic of naval warfare, it was a win.

But history never stays inside neat columns of tonnage sunk and convoys attacked. Beneath the waves at Sindangan Point lay a story that could not be squared with victory alone. Hundreds of Americans, worn thin by years of captivity, had perished not because their rescuers failed them, but because the machinery of war made them invisible. They were trapped in a ship that bore no marks of mercy, under guards who answered explosions not with surrender but with slaughter.

The tragedy of the Shinyo Maru is not a tale of blame, but of the cruel collision of necessity and ignorance. The crew of Paddle had no way to know. They fought the enemy as it appeared to them, through a periscope, as tonnage to be destroyed. The men below decks of Shinyo Maru could only cling to hope that the explosions they heard meant salvation, not death. Both groups were Americans, bound by the same war, separated by the iron walls of a Japanese freighter.

When the war ended and the survivors came home, their testimony filled in the missing pieces. The numbers told the story starkly: seven hundred and fifty prisoners aboard, eighty-two who lived to tell of it. And yet even in that grim count, there was meaning. Those survivors carried the memory of their shipmates, and through them the world learned what had happened in that dark hold.

For Paddle’s crew, the war went on. More patrols, more risks, more victories. But the shadow of September 7 lingered, part of the record forever. It reminds us that in war the line between triumph and tragedy is paper thin, and often invisible in the moment.

Today, when we recall the story of USS Paddle and the sinking of Shinyo Maru, we do so with a double measure of remembrance. We honor the submariners who fought with skill and bravery, and we honor the prisoners whose suffering ended in one final act of horror. Both groups were part of the same story, a story of men caught in the vast machinery of a world at war, where even victories could break the heart.

November 2018, by Mike Fitzpatrick

Leave a comment