When the USS Cod (SS-224) first slipped into the Pacific war, she was one of dozens of Gato-class submarines sliding down the ways in 1943. The war was still young for the Silent Service, but it had already turned into a proving ground for men and machines. By the time Cod was commissioned on June 21, 1943, under Commander James C. Dempsey, the submarine force had become America’s sharpest spear against Japan’s supply lines. Cod herself was a sleek, steel predator, long, lean, and packed with 24 torpedoes, a 5-inch deck gun, and the engines and batteries to make her a silent prowler beneath the seas. She was part of the answer to Japan’s sprawling empire: cut the lifelines, sink the ships, starve the war machine. But ships are only steel and rivets until men step aboard to bring them to life.

Fri, Sep 03, 1943 ·Page 3

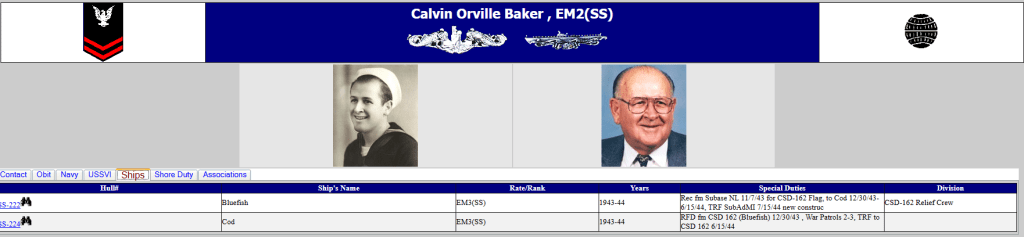

For Cod, one of those men was Calvin Baker. His story is not one of admiralty or decorations, but it is the story of countless young Americans, fresh out of school, handed a duffel bag, and told to fight a global war inside a steel tube. Calvin Baker graduated from Submarine School on September 3, 1943. For a young man, it was an accomplishment worth celebrating, but there was little time to savor it. The Navy needed men badly, and the war would not wait. Baker’s diploma was less a certificate than a set of orders. Within weeks, he was on his way to join the Cod (after a short month on the USS Bluefish).

The submarine he joined was already blooded. Cod’s first patrol had carried her into the Java Sea in late 1943. She came back to Fremantle, Australia, in December, still afloat and ready to fight again. It was during that refit that Baker reported aboard. He was stepping onto a combat veteran, a boat that already carried the smells of diesel fuel, sweat, and fear. The men aboard knew what the war sounded like, the rush of air diving, the explosion of torpedoes, the teeth-rattling concussions of depth charges. Baker would soon learn. On a submarine, there is no gentle welcome. There is no space for passengers. A new man is expected to pull his weight, to learn fast, and to make himself part of the crew. Baker’s teachers would not be instructors in classrooms but the unforgiving Pacific and a captain who expected nothing less than perfection.

On January 11, 1944, Cod sailed from Fremantle for her second war patrol, bound for the South China Sea and the waters around Java and Halmahera. Baker was aboard. It did not take long for the boat to find her stride. On February 16, Cod surfaced and destroyed a Japanese sampan by gunfire. It was small work, but every vessel sunk was one less carrying food, fuel, or troops to feed Japan’s war. Baker, perhaps manning a station topside or below, would have felt the strange thrill of firing a gun at sea, of watching wooden planks splinter under American shells.

Real prizes were ahead. On February 23, Cod caught a tanker, AO Zuiyo Maru, and delivered a death blow. Torpedoes slammed home, and the 7,360-ton vessel erupted in fire and smoke. For a young submariner, it must have been a sight that burned into memory, the sea itself swallowing a giant, the proof that their steel fish worked. Four days later, the Cod struck again, this time the cargo ship Taisoku Maru, 2,473 tons sent to the bottom. Baker, like every man aboard, knew this was why they were there. Every ship destroyed meant Japanese soldiers, factories, and civilians would go hungry or fight with less fuel and fewer bullets. The submarine war was brutal, but it was effective.

Then came February 29. Cod lined up on what was believed to be a Terutsuki-class destroyer, a hunter, not prey. The attack failed, and the tables turned. Japanese escorts thundered in with depth charges, forcing Cod deep. To live through a depth charge attack is to endure hell, the hull groaning under pressure, light bulbs rattling in sockets, dust and rust raining from overhead, men holding their breath as explosions rolled closer. For Baker, this was baptism by fire. Whatever innocence remained from submarine school, it was gone now. He was a submariner. When Cod returned to Fremantle on March 13, she was bloodied but victorious. Nearly 10,000 tons of shipping and a sampan destroyed, her battle flag growing crowded with symbols. The crew received the Submarine Combat Insignia. Baker had received something else, survival, experience, and the knowledge that he could endure what the war demanded.

After a short refit, Cod sailed again on April 6, 1944, this time bound for the Sulu Sea and waters off Luzon. Baker was aboard again, now a little more seasoned, a little less green, but no less vulnerable. The patrol climaxed on May 10, when Cod came upon a convoy that was the stuff of both dreams and nightmares, 32 ships, heavily escorted. For a submarine, it was the kind of opportunity that could make reputations or end lives. Cod crept in, silent and patient, then struck. Torpedoes tore into the destroyer Karukaya, 1,270 tons of Japanese steel sent to the bottom. More fish found their mark on the cargo ship Shohei Maru, a 7,256-ton merchantman. Flames and wreckage filled the sea, and Baker would have felt the surge of pride and fear mingled in every submariner, pride at the kill, fear at the inevitable retaliation.

The escorts did not disappoint. Depth charges hammered Cod, driving her deep and pounding her hull. Again, Baker lived through the soundscape of submarine survival, dull thuds, violent crashes, the creak of the boat under pressure. It is one thing to study such things in New London; it is another to live them 300 feet below the surface with death hammering at your door. Cod survived, and by June 1, 1944, she was back in Fremantle. The third patrol had proven the boat and her crew once more. For Baker, it meant a second set of battle scars etched into his memory.

Though Baker’s service aboard Cod is most clearly tied to her second and third patrols, the submarine’s war stretched on. On her fourth patrol in July 1944, she destroyed Seiko Maru and LSV-129. On her fifth, in the Philippines, she put Tatsushiro Maru down and pulled lifeguard duty for aviators shot down in combat. Her sixth patrol saw tragedy when a fire in the aft torpedo room claimed the life of S1c Andrew G. Johnson, the only Cod fatality of the war. The seventh patrol entered submarine lore. In July 1945, Cod rescued the stranded Dutch submarine O-19, taking off her entire crew, then scuttling the boat with explosives to prevent capture. The event was celebrated on Cod’s return with a cocktail glass symbol on her battle flag, a tongue-in-cheek nod to the drinks shared with their Dutch brothers-in-arms. By war’s end, Cod had become a veteran of the Pacific campaign, her name forever etched into the rolls of the Silent Service.

The Cod’s story did not end in 1945. Decommissioned, then recommissioned for NATO training, she was eventually retired to Cleveland, Ohio. Since 1976, she has served as a museum ship, unique among her peers for being preserved in original wartime condition. No tourist doors, no cut stairways, visitors climb aboard the way Baker once did. Her diesel engines still rumble, her 5-inch deck gun still looms, and her hull still bears the weight of history. In 2023, she celebrated 80 years since commissioning, a survivor not just of war but of time. For visitors, she is a living reminder of what it meant to serve beneath the sea. For men like Baker, she was a crucible, a home, and a battlefield rolled into one.

The historical record is silent about much of Calvin Baker’s life after the war. We know he was a member of the United States Submarine Veterans of World War II, one of the thousands who carried the memories of patrols and depth charges into the quiet years of peace. In many ways, his story is the story of the Silent Service itself. Not every man became famous. Not every patrol made headlines. But together, they carried the war across the Pacific, sinking ships, enduring attacks, and surviving odds that were grim from the start. Calvin Baker was one of them, a fresh graduate turned seasoned submariner, who lived to see the Cod return from war and endure into history. His name may not be on the battle flag, but his life was part of its legacy. And in remembering him, we remember all the young men who stepped aboard steel boats and vanished into the Pacific, prowlers in the silence, fighting a war that the world above rarely saw.

Sun, May 12, 2013 ·Page B6

Leave a comment