The Pacific War was not won by a single battle or a single weapon, but by the grinding, relentless pressure applied across thousands of miles of ocean. In that vast chessboard of sea lanes and islands, submarines played an outsized role. Among them was USS Bluefish (SS-222), a Gato-class submarine commissioned in May of 1943. She was not one of the glamour boats that made headlines back home, but she was steady, aggressive, and efficient, a hunter that earned the respect of the men who served in her.

Operating out of Australian ports like Fremantle and Brisbane, she patrolled the South China Sea, Celebes Sea, and the long approaches to the Philippines. Each patrol carried the possibility of weeks of monotony interrupted by sudden, violent moments of combat.

By the summer of 1944, the American submarine campaign had reached a peak. Japan’s lifelines were stretched and bleeding. Every tanker, every transport, every freighter lost to the torpedo meant fuel not delivered, troops stranded, factories starved. Bluefish and her sisters were strangling the empire one keel at a time.

And then came August 19, 1944. On that night, Bluefish would slip into history. Alongside USS Rasher, she fell upon one of the last great Japanese convoys, a lumbering mass of ships carrying men, supplies, and hope for a faltering empire. Out in the blackness, under rain squalls and against the pulse of enemy escorts, Bluefish delivered one of the decisive strikes of the submarine war. That night became her defining moment, and it remains a sharp reminder of how much damage a single submarine could do when opportunity met skill.

When Bluefish first entered service in mid-1943, she was quickly sent into action. The submarine force was already deep into its war against Japanese shipping, and every new boat was needed. On her first patrols out of Brisbane, she proved her worth. In September 1943 she intercepted Akashi Maru, a Japanese merchantman, and sent her to the bottom. A few days later, while shadowing the damaged vessel, she tangled with and sank Kasasagi, a Japanese torpedo boat. For a young submarine on her first cruise, it was an auspicious start.

Bluefish’s baptism did not stop there. Later that fall, she sank the large tanker Kyokuei Maru and damaged another oiler, Ondo. She also sent the elderly destroyer Sanae to the bottom. Submariners knew the value of such kills. Tankers were the lifeblood of the Japanese Navy, and destroyers were the very predators tasked with hunting the submarines. To take both from the fight was no small accomplishment.

The year 1944 brought more successes. In December, Bluefish sank Ichiyu Maru in the Java Sea, another blow against Japan’s dwindling merchant fleet. Soon after, she joined forces with USS Rasher in January to attack a Japanese convoy off Indo-China. Bluefish’s contribution was the sinking of Hakko Maru, a tanker of over six thousand tons. Again, fuel denied to Japan’s war effort.

March 1944 saw Bluefish at work in the South China Sea, where she torpedoed and sank the oiler Ominesan Maru. Then in June she struck again, sinking two more vessels, Nanshin Maru and Kanan Maru. By the middle of that year, Bluefish’s record was impressive. She was no longer an untested boat. Her crew was seasoned, experienced, and accustomed to the risks and rhythm of convoy hunting. They had fought through depth charges, endured long patrols in the tropics, and sent thousands of tons of shipping to the bottom.

It was this seasoned hunter that set out on patrol in July 1944.

Bluefish left Fremantle in July 1944 for her sixth war patrol. The orders took her into dangerous waters off the Philippines, where Japanese convoys funneled southward with reinforcements and supplies. Every submarine commander knew these routes offered rich opportunities if they could locate the prey and avoid the escorts.

USS Rasher was also in the area. The two boats were not working in close company, but their operations overlapped, and information passed between them by coded radio. Submarines were like lone wolves, but on rare occasions they could act in tandem, and this would be one of those occasions.

The target was Convoy Hi-71, a large group of Japanese ships bound from Japan toward the Philippines. It was a critical run. The convoy carried not just supplies, but reinforcements and the fuel to keep the fleet moving. Japan’s hold on the Philippines was under pressure, and Hi-71 was an effort to bolster it before the inevitable American invasion.

Convoy Hi-71 was heavily escorted, but the Pacific in 1944 was no longer favorable ground for Japan. Submarines prowled the lanes, aircraft struck from bases and carriers, and the empire’s ability to move freely was steadily shrinking. Into this picture steamed Bluefish, her crew alert and her commander ready to strike.

The sea was black and unsettled. Rain squalls swept across the surface, hiding ships one moment and revealing them the next. Just after two in the morning, Bluefish’s radar picked up the outlines of a formation. Convoy Hi-71 was ahead, moving at fourteen knots, zigzagging but steady. The range closed, the escorts prowled, and Henderson made his decision.

At 2:25 a.m. the first attack began. Four torpedoes from the bow streaked away into the dark. The men waited, tense, listening through the hull. Seconds passed, then the thunder came. One, two, three explosions reverberated through the boat. Though rain and darkness denied clear visuals, there was no doubt the fish had found their mark. Somewhere out there, a Japanese ship was reeling, but the convoy pressed on. Bluefish pulled away, then turned back for another strike.

By 3:55 she was in position again. Henderson ordered three more torpedoes fired. This time the results were unmistakable. At 4:01 a.m. flames burst skyward. A ship had been struck aft and was burning fiercely. It was later confirmed to be Hayasui, one of the largest oilers in the Japanese fleet, a vessel that also served as a seaplane carrier. She carried thousands of tons of fuel, the very lifeblood of the navy, and she was dead in the water.

Bluefish was not content to leave her crippled. For the next two hours she shadowed Hayasui, stalking her like a predator circling wounded prey. As dawn crept over the horizon, Henderson brought Bluefish in close. At 7:15 three more torpedoes slammed into the stricken oiler. The explosions shattered what remained. Fires raged, the ship sagged, and men in lifeboats pulled away as their vessel succumbed. Hayasui was gone, and with her another piece of Japan’s already desperate logistical puzzle.

But that was not all. During the action, Bluefish also damaged the transport Awa Maru, another large vessel that carried troops and supplies. Though she did not sink, the damage further weakened the convoy. Meanwhile, Rasher was at work elsewhere in the formation, scoring one of the most dramatic submarine hauls of the war. She sent the escort carrier Taiyō, the tanker Teiyō Maru, and the transport Teia Maru to the bottom.

Together, Bluefish and Rasher had ripped the heart out of Convoy Hi-71.

By the morning of August 19, Convoy Hi-71 was shattered. Hayasui lay at the bottom, Taiyō and several other ships were gone, and survivors were scattered across the sea. What was meant to be a vital reinforcement effort had turned into disaster. The loss of Hayasui alone was a crippling blow. Japan had only a handful of large oilers left, and each one lost meant the fleet was further starved of mobility. Without fuel, carriers could not sortie, escorts could not protect, and troop convoys could not reach their destinations.

The damage to Awa Maru and the destruction of other transports meant fewer reinforcements for the Philippines. American submarines had achieved exactly what was intended: choking Japan’s ability to sustain the war effort. The August 19 attack became one of the most successful coordinated submarine strikes of the war.

For the men aboard Bluefish, the night was a vindication of training, patience, and nerve. In the confusion of rain and darkness, relying on radar bearings more than eyesight, they had pressed home the attack and destroyed a giant of the Japanese fleet.

Bluefish did not rest after August. She continued her patrols into 1945, though by then Japanese shipping had dwindled. The targets grew fewer, but her record still grew. In July 1945 she torpedoed and sank the submarine I-351 in the South China Sea. Four days later she sank a submarine chaser by gunfire near Sumatra. She also carried out lifeguard duty, rescuing American aviators who had ditched at sea. In one poignant case, she pulled two men from the water while their pilot, Jacob Matthew Reisert, died of wounds after bringing his crew to safety.

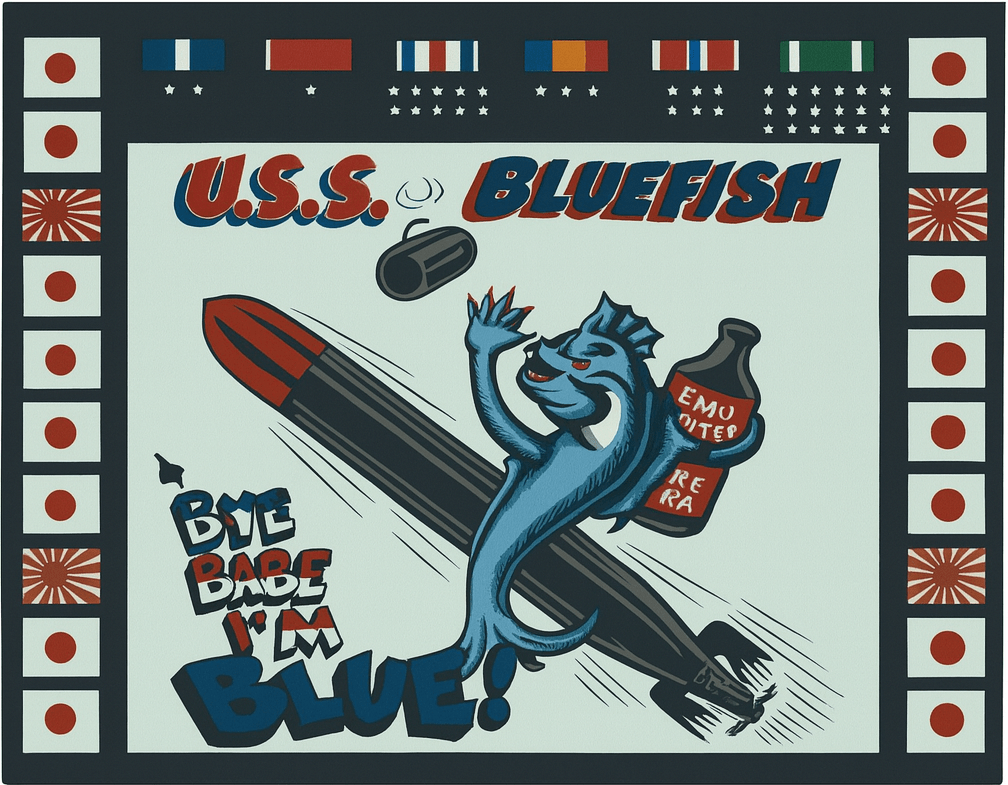

After the war Bluefish returned home. She was decommissioned in 1947, briefly brought back into service in 1952 for training duties, and finally struck from the Navy’s rolls in 1958. By 1960 she was scrapped. Over her wartime career she earned ten battle stars and a quiet but firm place in the annals of the submarine force.

Bluefish was never the most famous submarine of the war, but her record stands among the solid and the steady. She was a boat that did her job, time after time, across two years of hard fighting. On August 19, 1944, she stepped into history with the destruction of Hayasui, striking a blow that went far beyond the tonnage sunk. She deprived the Japanese fleet of fuel and mobility at a critical moment, helping to ensure that the empire’s last stand in the Philippines would come under-supplied and under-supported.

Her story reflects the reality of the submarine campaign. It was not glamorous. It was long stretches of patience, nerve-wracking attacks in the dark, and the knowledge that one mistake could mean a quick death under depth charge barrages. Yet the results speak for themselves. Japan’s sea lanes collapsed, her navy was immobilized, and her empire was strangled into defeat.

Bluefish’s defining night remains August 19. In the company of Rasher, she showed the devastating effectiveness of American submarines at their peak. She was not just a hunter in the dark. She was part of the slow crushing of an empire, one torpedo at a time.

USS Bluefish War Patrol Report – 6th Patrol, August 1944. National Archives Catalog ID 139738842.

USS Bluefish (SS-222) – War Record. Compiled operational summary, WWII submarine patrol files.

USS Bluefish (SS-222) – DANFS Entry. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Naval History and Heritage Command. http://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/bluefish-i.html.

Pigboats.com – Kill Record of USS Bluefish. Archived July 2022. http://pigboats.com/ww2/bluefish.html.

NavSource Naval History – USS Bluefish Photo Archive. http://www.navsource.net/archives/08/08222.htm.

Blair, Clay. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975.

Friedman, Norman. U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 1995.

Bauer, K. Jack, and Roberts, Stephen S. Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991.

USS Bluefish (SS-222) – Wikipedia Article. Includes construction, patrols, and postwar career. Retrieved August 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Bluefish_(SS-222)

Leave a comment