In the summer of 1945, USS Spikefish (SS-404) was a young boat in a veteran’s war. A Balao-class submarine commissioned only months earlier, she was part of the U.S. Navy’s relentless undersea campaign that had, by then, strangled Japan’s maritime lifelines. Built for endurance and stealth, the Balao class represented the peak of American submarine design in World War II, long-ranged, heavily armed, and capable of diving deeper than their predecessors. Spikefish was on her second war patrol in August 1945, operating in the waters south of Japan, where danger still lingered in every sonar ping and radar contact.

By this point, the war was teetering toward its end. Allied bombers had reduced Japanese cities to rubble, the Imperial Navy was shattered, and the atomic bombs had just been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet in the far-flung reaches of the Pacific, submarine crews could not assume the fight was over. Orders still sent them hunting, and enemy ships still sailed. For the men aboard Spikefish, there was no crystal-clear moment when peace replaced war, only the knowledge that at any instant, the next contact could be the last engagement of their lives. That moment would come soon enough, in the form of a final, fateful target.

In the closing weeks of the Pacific War, the Imperial Japanese Navy was a shadow of its once formidable self. Its major surface combatants lay at the bottom of the ocean or rusting away in harbor, fuel supplies were critically short, and merchant shipping losses had crippled the empire’s ability to sustain its forces. Yet even in these desperate final days, Japan still maintained a small number of operational submarines. Among them was I-373, a vessel of the Type D1 transport submarine design. Unlike the large fleet submarines that had once been dispatched on offensive patrols, the D1 boats were essentially underwater cargo carriers. Their primary purpose in 1945 was to run supplies to isolated garrisons, particularly those bypassed by the Allied island-hopping campaign.

I-373 had been commissioned only in January of 1945, and her role was strictly logistical. She was tasked with transporting rice, ammunition, and other essentials to Japanese outposts now cut off by Allied naval and air power. By August 1945, she had been ordered on a supply run to Takao, in Formosa (now Kaohsiung, Taiwan). Her mission was one of survival for both the crew aboard and the garrisons awaiting her cargo, but it was also a gamble. Allied patrol lines still lay thick across the approaches to Japan, and U.S. submarines had been briefed that even non-offensive Japanese vessels were legitimate wartime targets.

USS Spikefish was among those submarines on watch. She had been assigned patrol duties in the East China Sea, south of Japan and within striking range of the vital lanes that still carried what little traffic remained between the Home Islands and Formosa. Spikefish’s orders were clear: continue aggressive operations against enemy shipping until further notice. With the war’s end rumored but not yet confirmed, there was no room for hesitation.

On the morning of August 13, 1945, Spikefish’s radar picked up a contact at a range of approximately 14,000 yards. The contact appeared small, moving at a steady pace, and unescorted. The initial reaction aboard was one of curiosity mixed with caution. The Japanese were known to operate both decoy vessels and lone submarines in these waters, and this target’s profile matched that of a possible undersea opponent running on the surface. The man in command, Lieutenant Commander Robert Raymond Managhan, a career officer with a reputation for precision and calm under pressure, ordered the submarine to shadow the contact while plotting its course and speed.

Conditions were favorable for a surface approach. The morning light offered enough visibility to track the target without revealing Spikefish’s position, and the sea state allowed the crew to keep steady radar and optical bearings. Over the next two hours, the American submarine closed the distance, confirming that the contact was indeed a Japanese submarine. This was a rare sight in the final days of the war, as few enemy subs dared operate in contested waters without air cover.

Managhan made the decision to attack. Spikefish maneuvered into firing position, choosing a setup that would allow her to launch a spread of torpedoes across the target’s projected path. At 4,000 yards, the crew readied six forward tubes. Torpedo data computer settings were checked and double-checked, and the boat’s firing party stood by for the order. At the appropriate moment, Managhan gave the command, and the first warshot leapt from the tube, followed in rapid succession by the others in the spread.

Moments later, the crew heard and felt the unmistakable rumble of a torpedo detonation. Through the periscope, they saw I-373 shudder under the impact. Water and debris erupted into the air, and within minutes the Japanese submarine began to settle by the bow. Observers noted no sign of counterattack or return fire. The damage had been swift and overwhelming.

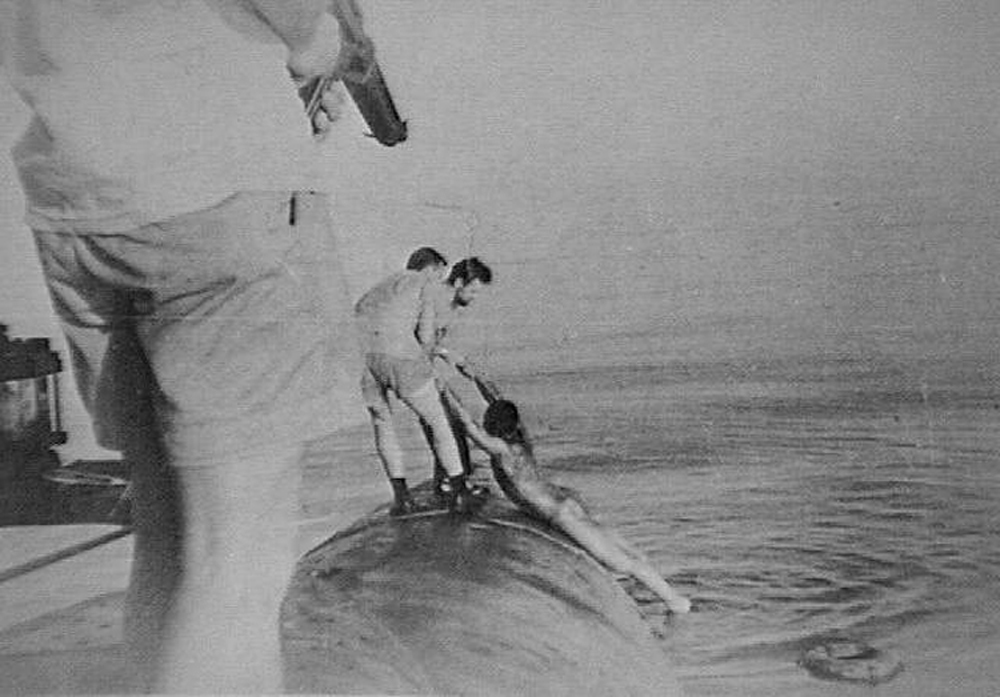

Within a short time, I-373 slipped beneath the surface, taking most of her crew with her. Spikefish remained in the area, scanning for survivors. Records indicate that only a handful of men were seen in the water, and none were recovered by the American submarine. The action was logged and reported to headquarters, but there was no time for celebration. Even in these final days, submariners knew that lingering too long at a kill site could invite unwanted attention from aircraft or other patrols.

The sinking of I-373 would later be recognized as historically significant. Unbeknownst to those aboard Spikefish at the time, this attack marked the last sinking of an enemy submarine in World War II. It was a final lethal exchange in a long and brutal undersea conflict that had begun for the United States with the loss of USS Sealion at Cavite in December 1941. For Spikefish’s crew, the moment was another successful patrol action in a war that seemed to have no clear ending. Only later would they understand that their torpedoes had closed the final chapter in submarine-versus-submarine combat of the conflict.

The engagement also underscored the relentless nature of submarine warfare in the Pacific. Even as diplomats worked to bring about Japan’s surrender, men at sea continued to fight with full commitment to their orders. The timing of Spikefish’s warshot was a reminder that history rarely unfolds in clean, tidy sequences. The war was not officially over, and as long as it remained so, every encounter could mean life or death.

In the official patrol report, the tone was professional and matter-of-fact, as if recording just another day’s work. Yet the crew must have felt a complex mix of emotions. Pride in their skill and success was tempered by the knowledge that the men aboard I-373 had perished just days before peace would have spared them. For veterans of the Silent Service, this moral weight was a familiar burden, carried in the quiet moments long after the guns had fallen silent.

Spikefish’s final warshot was not only the last act of its kind in the Pacific War, it was a symbol of the endurance, precision, and professionalism of the U.S. submarine force to the very end. It was the work of a well-trained crew executing their mission without hesitation, in a war where hesitation could be fatal. And while the world would soon turn to celebrations of peace, the memory of that morning in August 1945 would remain etched into the ship’s history and the minds of her crew.

When word finally reached USS Spikefish that hostilities had ceased, the news seemed almost unreal. It came through in clipped, official Navy language, the sort of phrasing that stripped away any sense of drama. Yet behind those words lay the unthinkable: the war that had defined every waking moment for years was over. For the crew, who had fired their last torpedoes only days before, the shift from combat alertness to peacetime orders felt abrupt, almost jarring.

Contemporary accounts, preserved in fragments from the patrol report and later interviews, reveal a range of reactions. Some men greeted the announcement with quiet nods and a few murmured comments, as if acknowledging the end of a long, grueling shift rather than a global conflict. Others allowed themselves small celebrations, a cup of coffee poured with a smile, a handshake shared between watchstanders. There was no spontaneous cheering on deck, no victory dance in the control room. The transition from war to peace, at least aboard Spikefish, was marked by a subdued dignity.

Part of the restraint came from disbelief. Just days earlier, they had hunted and destroyed I-373, knowing full well that hesitation could have cost them their own lives. That fight had been real, deadly, and absolute. Now they were being told that the enemy they had been trained to find and sink was no longer to be engaged. The contrast was sharp, even disorienting. In the minds of many, the war could not simply end with a message over the radio; it had to be confirmed by time and the absence of danger.

For the veterans aboard, some of whom had served through multiple patrols, the end of the war carried a quiet weight. It was relief, yes, but also reflection on the friends lost and the battles fought. The knowledge that they had survived when so many others had not lent a solemn undertone to the moment. Several crew members later recalled that the mood was not one of triumph but of gratitude, mixed with an awareness of how close they had come to sharing the fate of other submarines that never returned.

In the pages of the official log, the event is recorded without flourish: the time, the source of the message, the change in orders. But between those lines lies the story of a crew who had fought to the very last days of the Pacific War, only to lay down their arms at the edge of victory. The ocean around them was the same, the hum of the engines unchanged, but the mission that had carried them halfway around the world was suddenly complete. Peace had come, and with it, the long journey home.

With the war’s end confirmed, USS Spikefish received new orders directing her to proceed to Saipan. The tone of the message was routine, but the shift in mission was unmistakable. No longer were they to patrol for enemy contacts or maintain a firing solution on every suspicious radar return. The focus now was on transiting safely, conserving fuel, and preparing the boat for the long voyage ahead.

The days underway to Saipan carried a different rhythm. Watches were still stood, maintenance still performed, but there was a lighter air among the crew. Some men began packing away personal gear, while others took the time to clean spaces that had been neglected during combat patrols. The galley turned out the occasional special meal, and the talk in the mess decks often turned to home — wives and sweethearts, plans for civilian life, and the hope of seeing familiar streets again. Yet even in these more relaxed moments, the professionalism of the Silent Service remained. The sea was unpredictable, and the crew treated the trip as another mission to be completed without incident.

Upon arrival at Saipan, Spikefish joined a port crowded with ships in various stages of war’s aftermath — transports loading men for the trip home, damaged vessels awaiting repair, and other submarines coming in from their last patrols. Here the crew received their formal postwar orders, confirming that their combat role was finished. There was a sense of shared understanding between the crews in port. Everyone knew the war was over, but the business of bringing men and ships home would take time and careful coordination.

From Saipan, Spikefish began her homeward voyage to the United States. The route took her across the vast Pacific to Pearl Harbor, a stop that allowed for refueling, minor maintenance, and perhaps a moment to reflect on the fact that she had departed those waters a warship and would return a peacetime vessel. From Hawaii, she steamed on to the mainland, arriving at her assigned port with the war behind her and an uncertain peacetime future ahead.

For the men who stepped ashore, the moment was more than just the end of a patrol. It was the conclusion of their part in the largest naval war in history, a transition from the tense days of combat to the quieter, though no less meaningful, duties of life after war. Spikefish had brought them home, and that alone was cause for pride.

Following her return from the Pacific, USS Spikefish transitioned into the peacetime Navy, adapting to new missions in a rapidly changing world. No longer needed for wartime patrols, she became a vital platform for training, readiness exercises, and fleet support. Over the next two decades, Spikefish participated in anti-submarine warfare drills, sonar development programs, and joint operations designed to hone the skills of both submarine crews and surface ship hunters. She frequently operated along the U.S. East Coast and in the Caribbean, serving as a reliable training partner for destroyers, patrol aircraft, and NATO allies.

One of the most notable milestones in her career came in 1962, when Spikefish recorded her 10,000th dive. In the submarine service, such a number speaks to the endurance of both vessel and crew. Every dive represents not only the execution of a maneuver but also the trust placed in the submarine’s systems and the skill of those who operate them. Achieving this figure marked her as a veteran of thousands of hours spent beneath the waves, a testament to her durability and the professionalism of the men who sailed her.

As technology advanced, Spikefish’s role evolved further. By the late 1960s, she was primarily employed as a target submarine for anti-submarine warfare training and weapons testing. This work, though lacking the drama of wartime patrols, was critical to ensuring that the next generation of naval forces could meet the challenges of the Cold War. She provided realistic submarine contacts for surface ships and aircraft, helping refine detection methods and tactics that would be essential in any potential conflict with the Soviet Union.

Ultimately, age and technological obsolescence caught up with Spikefish. She was decommissioned and struck from the Naval Vessel Register in 1973, bringing to a close nearly three decades of service. Her final years had been spent not in combat but in preparing others for it — a fitting legacy for a boat that had already proven herself in war.

USS Spikefish occupies a distinct place in submarine history. In August 1945, her torpedoes sank I-373, the last Japanese submarine lost in World War II, effectively closing the book on undersea combat in that conflict. She had proven her combat readiness in the crucible of war, carrying out her orders with precision even in the war’s final hours.

In peacetime, Spikefish transformed into a workhorse of the Cold War Navy. She trained countless sailors, tested new tactics, and maintained the operational edge of the fleet. Her 10,000+ dives were not just a statistic but a symbol of her long-standing value to the service.

For submarine veterans, Spikefish represents both the sharp end of the spear and the quiet dedication that follows victory. She reminds us that history is shaped not only by the battles fought but also by the long years of preparation, training, and vigilance that keep a fleet ready. For the U.S. Navy, her story is a reminder of the adaptability and resilience of its submarines and the men who serve aboard them. Spikefish’s journey from wartime hunter to peacetime trainer stands as a proud chapter in the heritage of the Silent Service.

NavSource Naval History – USS Spikefish (SS-404) Photographic Archive. Available at: http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08404.htm

Warship Wednesday, August 18 2021: The Last Sub Killer.” Last Stand on Zombie Island. August 18 2021. Accessed 08/14/2025. https://laststandonzombieisland.com/2021/08/18/warship-wednesday-august-18-2021-the-last-sub-killer/

uboat.net – USS Spikefish (SS-404). Available at: https://uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/3137.html

On Eternal Patrol – Japanese Submarine I-373. Available at: https://www.oneternalpatrol.com/Japan-I-373.htm

CombinedFleet.com – Tabular Record of Movement: I-373. Available at: http://www.combinedfleet.com/I-373.htm

Leave a comment