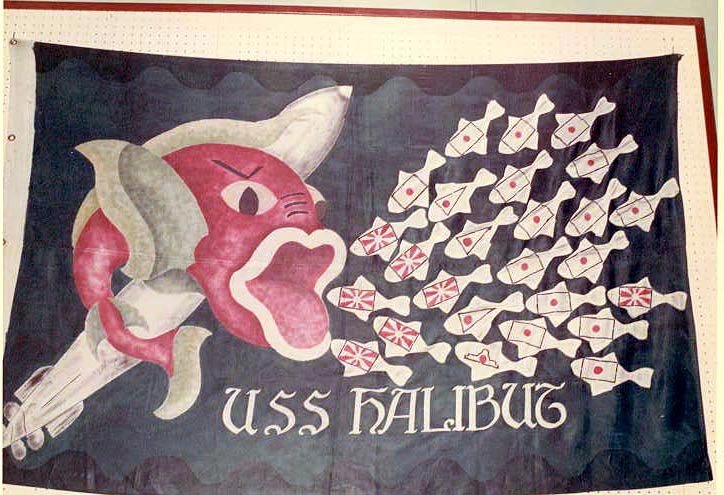

The base commander’s voice carried over the assembled crew on the warm August day. “Torpedoman’s Mate First Class James H. Howard.” He stepped forward, eyes straight ahead, as the medal was pinned to his dress blues. The citation spoke of meritorious service on war patrols. The words were official, clipped, and neat, but they could never match the reality of the months spent in the torpedo room of a fighting boat. He had already been to sea before the war, qualifying on USS Pollack in 1938, but the first three patrols aboard USS Halibut had been his real test.

The first patrol began in August 1942. Halibut sailed from Pearl Harbor into the long gray swells of the Aleutians. Howard remembered the cold seeping into the steel, the dampness that never left his clothes, and the constant smell of oil and machinery. Their orders were to search Chichagof Harbor and the waters around Kiska. Much of the time was spent submerged in silence, the crew listening for a hint of screws on the sonar. When they surfaced, the deck watch faced a wind that cut straight through their gear. Days stretched with no contact, just the routine of drills, equipment checks, and constant maintenance on the Mark 14 torpedoes. On August 23 they finally met a freighter and opened fire with the deck gun. Howard heard the boom and felt the shudder through the hull, but the exchange ended without a sinking. They put into Dutch Harbor in late September without having sent an enemy ship to the bottom, but with a sharper edge to their crew.

The second patrol began in October, again in the Aleutians. It was colder now, and the seas rougher. On October 11, the excitement in the forward room built quickly when the periscope brought in the silhouette of what looked like a large freighter. Orders came to prepare tubes, outer doors ready. The shot was never fired. As they surfaced for the attack, the target’s hidden guns opened up. The “freighter” was a Q-ship, bristling with concealed weapons and even torpedo tubes. Shells landed close, their sharp clang carrying into the torpedo room. Howard braced himself as the boat went deep, hearing the rush of water past the hull as they turned away. The encounter left a bitter taste. They returned to Dutch Harbor late in the month, then on to Pearl Harbor, having seen firsthand how the enemy could lure a submarine into a trap.

The third patrol took them far from the fog and cold. They left Pearl on November 22, 1942, bound for the waters off northern Japan. Howard spent much of the transit in the narrow confines of the forward torpedo room, checking depth settings, inspecting firing mechanisms, and drilling the crew on loading procedures. On the night of December 9, Halibut began shadowing a convoy. The next morning, Howard stood at his station as the captain called down the orders. Tube one fired, then tube two, then the rest of the spread. The jolts came one after another. A hit amidships on one ship. Two torpedoes into another sent her under quickly. Two days later they found Gyukozan Maru and sank her as well. Each attack was followed by the hammering of depth charges, the air in the torpedo room turning thick and tense, dust shaking from overhead piping. On December 16, they struck again, damaging one ship so badly she was run aground and abandoned. By the time they returned to Pearl Harbor on January 15, 1943, the crew had four ships to their credit and the knowledge they had struck directly at the enemy’s lifeline.

Howard’s memories of those patrols were more than the tally of ships sunk. He recalled the rhythm of life aboard: four hours on watch, four hours off, the smell of coffee drifting in the mess, the way a mug would rattle in its holder when the diesels roared. He remembered surfacing at night to charge batteries, the sudden relief of fresh air, and the quiet conversations with shipmates under the stars.

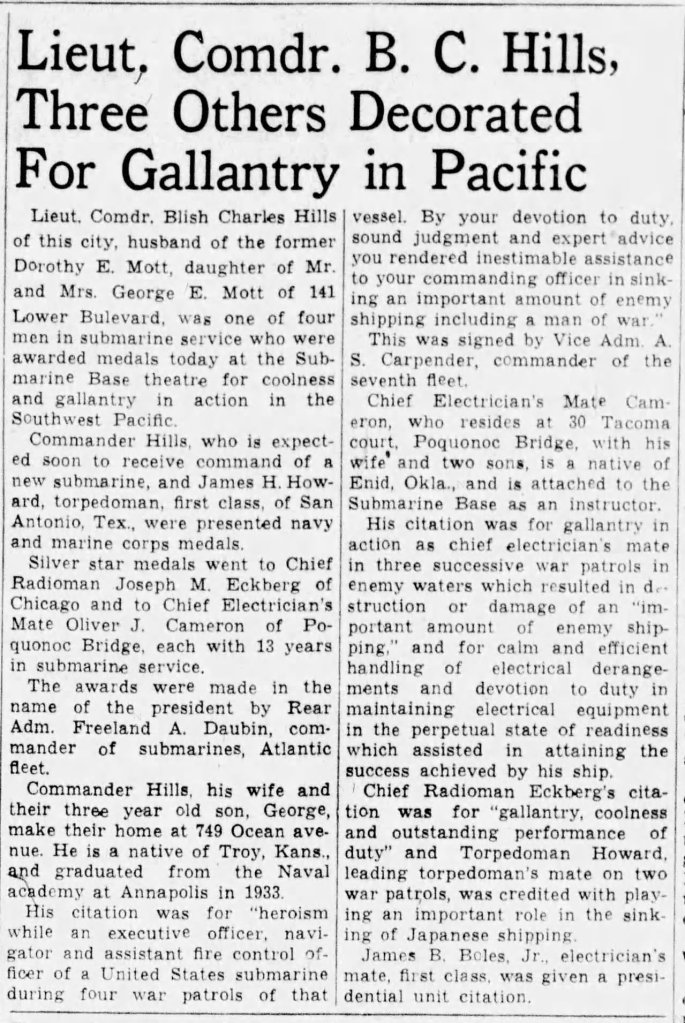

Standing at the award ceremony in 1943, he knew the medal was as much for the men who had stood beside him in that cramped torpedo room as it was for him.

Years later, in 1991, the obituary in his hometown paper told the bare facts: James H. Howard, 73, U.S. Navy veteran of World War II submarine service, decorated for actions aboard USS Halibut, qualified in submarines on USS Pollack, passed away quietly after a long life. Survived by family, remembered by shipmates. It didn’t speak of the cold Aleutian swells, the metallic tang of the torpedo room, or the sound of a hit reverberating through steel. The printed words did not carry the feel of the boat settling into the depths to escape the enemy. Those belonged to the men who were there, and to the sea itself.

National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). [Record description for National Archives Identifier 74822544]. In National Archives Catalog. Retrieved August 13, 2025, from https://catalog.archives.gov/id/74822544

United States Navy. The Fleet Type Submarine. Originally published as NAVPERS 16160, June 1946. Reprint edition. Periscope Film LLC, www.periscopefilm.com.

“Torpedoman’s Mate Honored.” The Day (New London, Connecticut), August 14, 1943, p. 11. https://www.newspapers.com/image/969118866/

Navy Department, Bureau of Ordnance. Torpedoes Mark 14 and 23 Types: Ordnance Pamphlet 635 (1st Revision). 1945. Scanned version hosted on maritime.org (accessed August 13, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.maritime.org/doc/torpedo/index.php

Galantin, L. J., Admiral, U.S.N. (Ret.) Take Her Deep!: A Submarine Against Japan in World War II. Introduction by Edward L. Beach. New York: Pocket Books, 1988. ISBN 0-671-66126-4.

Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975. ISBN 0-397-00753-1 (Standard Edition), ISBN 0-397-01089-3 (Deluxe Edition).

Roscoe, Theodore. United States Submarine Operations in World War II. Written for the Bureau of Naval Personnel from material prepared by R. G. Voge, W. J. Holmes, W. H. Hazzard, D. S. Graham, and H. J. Kuehn. Designed and illustrated by Fred Freeman. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1949. ISBN 0-87021-731-3.

Library of Congress. John W. Close Collection (Veterans History Project). Interview transcript and video. Accessed August 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.42041/

Contribution: Provided baseline details on torpedo gang duties, submarine school pipeline (Great Lakes, Newport, San Diego), and transition to operational patrols out of Pearl Harbor in 1942. Helped set the “forward torpedo room as my world” perspective in the opening.

The National WWII Museum, Digital Collections. Raymond Birdsall Oral History. WW2Online.org. Accessed August 2025. https://www.ww2online.org/view/raymond-birdsall

Contribution: Described the four-on, four-off watch routine, the red-lit torpedo room, and the tension when manning the firing button during action. Informed the sequence where the fictional narrator hears “Contact bearing zero-nine-zero” and preps the tubes.

Library of Congress. Billy Arthur Grieves Collection (Veterans History Project). Interview transcript and summary. Accessed August 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.74760/

Contribution: Discussed faulty torpedo exploders and the frustration of firing duds, influencing the narrator’s muttered curses about the Mark 14s and the memory of past patrol failures.

The National WWII Museum, Digital Collections. Billy Arthur Grieves Oral History. WW2Online.org. Accessed August 2025. https://www.ww2online.org/view/billy-grieves

Contribution: Expanded on the “hit and miss” nature of early-war torpedoes, and switching to the deck gun after failed runs. This fed into the “one hit echoed back… the other fish never came back” section.

Library of Congress. George Worley Collection (Veterans History Project). Audio interview. Accessed August 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.54077/

Contribution: Provided broad 1938–45 submarine service context and descriptions of Pacific patrols, including the shift between routine and sudden action. Helped with the “routine always returned” closing section.

Library of Congress. Stanley G. Coates Collection (Veterans History Project). Interview and summary. Accessed August 2025. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.75185/

Contribution: Added the electrical side of torpedoman duties, influencing the tube control and green-light readiness descriptions.

The National WWII Museum, Digital Collections. Robert Lents Oral History. WW2Online.org. Accessed August 2025. https://www.ww2online.org/view/robert-lents

Contribution: Gave prewar and early-war torpedo room atmosphere, crew camaraderie, and the feeling of being cut off from the outside world during long patrols. Informed the narrator’s “the boat felt smaller every day” line.

The National WWII Museum, Digital Collections. James Allen Oral History. WW2Online.org. Accessed August 2025. https://www.ww2online.org/view/james-allen

Contribution: Illustrated motivations for seeking submarine duty in 1942, which subtly informed the narrator’s focus on the work, the pride in the tubes, and the mindset of being ready for the next firing order.

Leave a comment