She was old by the standards of war, yet USS Pike (SS-173) had not lost her bite. By the summer of 1943, the Porpoise-class submarine had already patrolled the Pacific through some of its darkest days. She had been on the front lines when the war broke out, prowling the waters off the Philippines. She had weathered early operations out of Darwin, ducked depth charges near Wake Island, and fired torpedoes into the teeth of Japanese convoys off Truk. But nothing in Pike’s history to that point matched the success of her eighth war patrol.

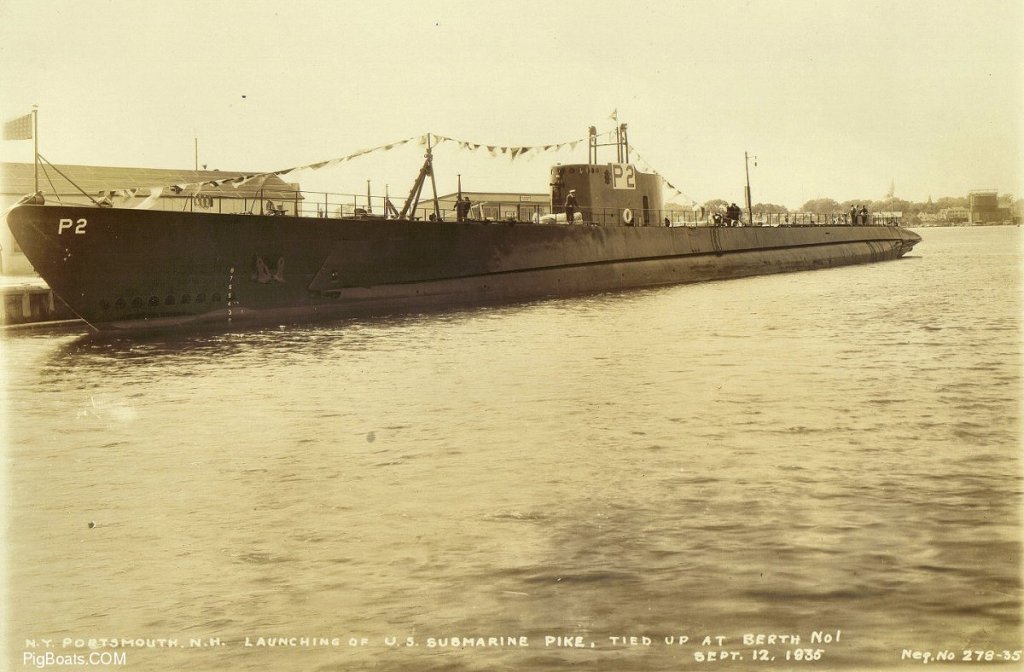

Pike had been launched in 1935 from the Portsmouth Navy Yard in New Hampshire. She was a pioneer in her own right, the first all-welded submarine in the U.S. Navy, which gave her a deeper dive capability than her riveted sisters. That extra depth would come in handy, but not right away. Before the war, Pike was shuffled around from Atlantic to Pacific, then on to the Philippines. When the war started, she was already close to the action. Her early war patrols were mostly quiet. Sightings were frequent. Opportunities were not. By the end of her seventh patrol, Pike had only two damaged enemy ships to her credit.

Then came July and August of 1943.

The eighth war patrol of USS Pike (SS-173), began on July 22 and lasted until September 9, 1943, was her most successful and perhaps her most dramatic.

On July 22, Pike cast off from the Submarine Base at Pearl Harbor under escort, making her way toward Midway. Routine training dives were performed during transit, but all was not well. On July 27, Pike turned back to Midway after her SD radar failed to detect the air escort. The fault was critical enough to warrant return and repair. By the next morning, the radar was functioning again, and Pike finally slipped out into the open Pacific, bound for the waters near Marcus Island and the Marianas.

She crossed the International Date Line on July 30. The crew trained with the 20mm gun, practiced trim dives, and engaged in battle surface drills. Life on patrol was a mixture of monotony and nerves. On August 3, the submarine dove to avoid a single-wing aircraft, another reminder that even before the shooting started, war was always close.

The first action came in the early hours of August 5. For nearly twelve hours on the 4th, Pike tracked a medium-sized tanker moored at Marcus Island. That evening, she noted the increased smoke from the target, then watched as the ship and its escort cleared the pier. It was too dark for a submerged attack. Pike waited, surfaced, and followed. Just before 0300 hours, the crew went to battle stations. They maneuvered to the tanker’s starboard beam and fired three torpedoes at a range of 1,500 yards. All three struck home. The tanker, later identified as the Shoju Maru, exploded. She tried to fight back with a flare and some sporadic shellfire, but within minutes, she was gone. Pike reversed course and slipped into the dark, unscathed.

Two days later, Pike sighted a different kind of prize: an auxiliary aircraft carrier of the Kasuga Maru class, steaming with a Fubuki-class destroyer at high speed. This was no merchantman. The carrier zig-zagged sharply. Pike submerged and began her approach. She intended to fire from both bow and deck tubes. A miscommunication sent one fish off early, but McGregor quickly adjusted. Four torpedoes followed from the bow, then one more from the deck. At least two explosions were heard. The carrier’s gunners responded immediately, firing at the periscope. The destroyer charged. Pike dove to 240 feet, encountering a thermocline that helped her evade. Three depth charge attacks followed. The last was dangerously close. But Pike endured and later surfaced in a rain squall that offered some protection.

In the days that followed, Pike reconnoitered Asuncion and Maug Islands and examined Pareco Vola (Douglas Reef). She found no worthwhile enemy targets there, only rocks, waves, and evidence of habitation in the form of huts. On August 16, she spotted a ship which turned out to be the Japanese hospital ship Takasago Maru, brightly lit and steaming at high speed. Rules of war were followed. Pike let her go.

CO of Pike on her final War Patrol

August 22 brought the third major contact. Smoke on the horizon led to the sighting of a Japanese convoy—six cargo vessels under Chidori-class escort. Pike made a submerged approach, but confusion and positioning issues led to a missed opportunity. The ships were zig-zagging heavily. With daylight slipping away, her CO, LCDR Sandy McGregor, who would receive the Silver Star for this patrol, decided to circle and try again at night.

Just before midnight, Pike struck. She fired two torpedoes from the bow tubes at a Gosei-class freighter, followed by two more at a larger freighter with a well deck. One torpedo hit. Smoke rose. Then came the escort, furious and fast. Gunfire opened up. Shells splashed within range of the bridge. Pike dove again. Depth charges rained down. They rocked the hull, but the boat held. By early morning, she was surfaced and shadowing the convoy again.

On August 24, Pike closed again, determined to land another blow. She had only one forward torpedo remaining, so McGregor opted for a stern-tube attack. Two torpedoes were launched at a Gosei-class freighter. A water column rose beside the bridge of the target. Explosions followed. The ship slowed. Though still afloat, she was clearly damaged. The escort responded with depth charges but failed to find their mark. Pike slid away.

As the patrol continued, Pike encountered little of strategic interest. On August 29, she scouted Pajaros Island, hoping to find a Japanese airstrip. The island had been recently scorched by a volcanic eruption, and no base was found. The following day, Maug Island was surveyed. Some huts and structures were visible, but no worthwhile installations. Radar checks showed the equipment was fully operational.

The final days of the patrol were spent cruising eastward, avoiding aircraft, checking radar, and preparing for return. On September 9, Pike arrived back at Pearl Harbor, her mission complete.

She had been at sea for 49 days, 31 of them in hostile waters. She had sunk a tanker and damaged three other ships, including an aircraft carrier. For a boat that had spent most of its war quietly watching the horizon, this patrol changed everything. The old Pike had found her moment. And her crew had proven that even in a war of giants, skill and aggression still mattered.

After the patrol, Pike was reassigned to the Atlantic. She left Pearl Harbor for New London in late September. Her days as a combat boat were done. For the rest of the war, Pike trained new crews. Fresh-faced sailors who would go to sea aboard newer, sleeker, and faster boats cut their teeth on her controls.

She was decommissioned in 1945. For a time, she served the Naval Reserve in Baltimore. By 1956, she was stricken from the register. A year later, she was sold for scrap.

Yet for one hot stretch in the summer of 1943, the old Pike showed the kind of steel that welded her together. She found her prey. She delivered her blows. She came home. And she earned her place in the proud history of the Silent Service.

National Archives Catalog

“U.S.S. Pike – Eighth War Patrol Report.” National Archives Catalog, Record Group 38. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/74831234. Narrative version by David Ray Bowman FTB1(SS) 08.05.2025

Blair, Clay, Jr.

Blair, Clay Jr. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. New York: Chilton Book Company, 1975. Second printing.

ISBN (Deluxe Edition): 0-397-01089-3, Page 435

Roscoe, Theodore. United States Submarine Operations in World War II. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1949. pgs 280-281

Friedman, Norman

U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1995.

ISBN: 1-55750-263-3

PigBoats.com (archive23)

“USS Pike (SS-173).” PigBoats.com. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://archive23.pigboats.com/subs/173.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command (DANFS)

“Pike II (SS-173).” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/p/pike-ii.html.

Wikipedia

“USS Pike (SS-173).” Wikipedia. Last modified July 2025. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Pike_(SS-173).

NavSource Naval History

“USS Pike (SS-173).” NavSource Online: Submarine Photo Archive. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://www.navsource.net/archives/08/08173.htm.

Leave a comment