In the cold gray dawn of July 5, 1942, the crew of USS Growler (SS-215) was deep in the fight. She was five miles northeast of Kiska Harbor, patrolling the rough waters of the Aleutians as part of the silent service’s early wartime thrust into the North Pacific. The island, then held by Japanese forces, was a linchpin in the enemy’s bold move to stretch their Empire’s grip eastward across the Aleutian chain.

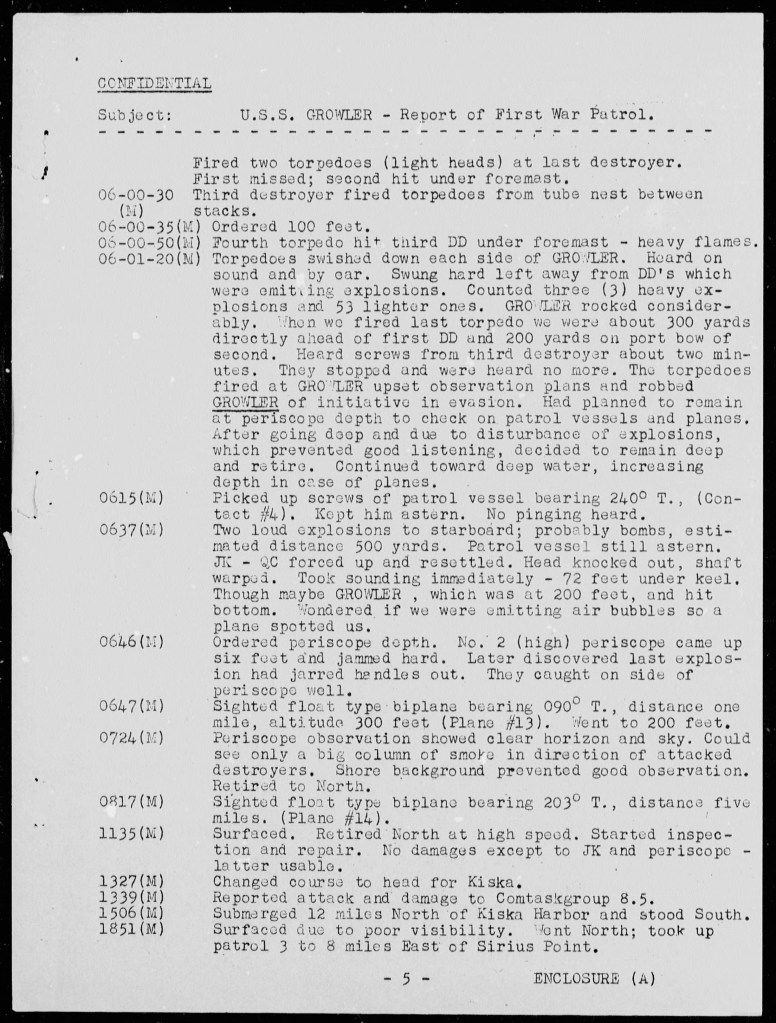

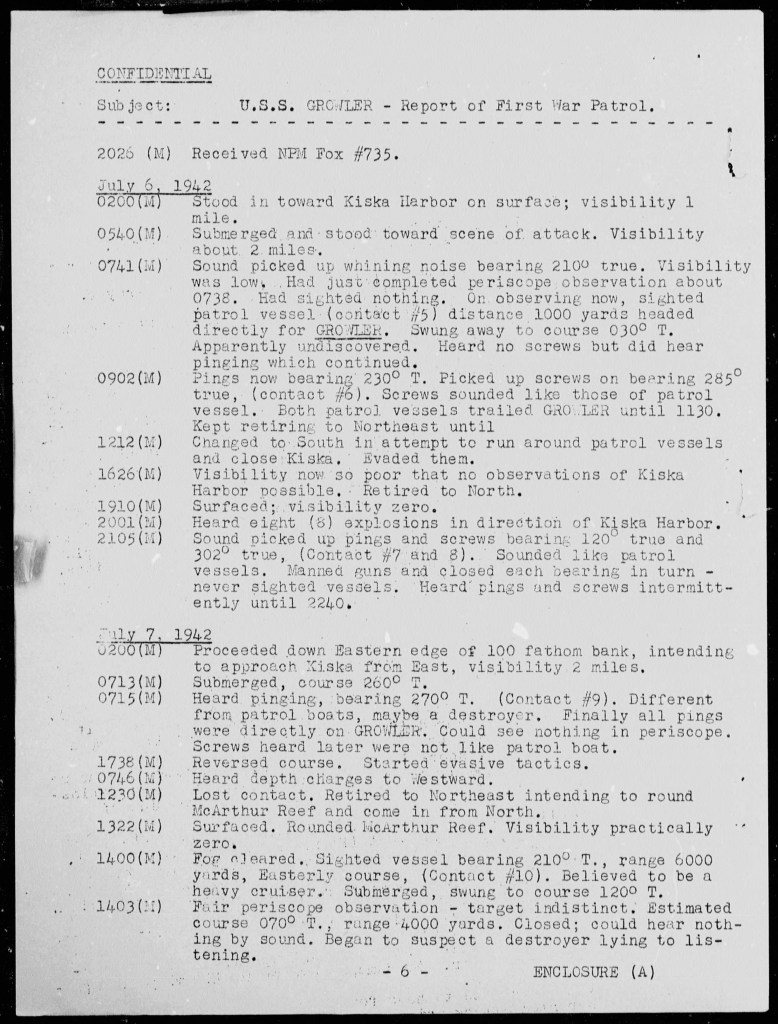

For the men aboard Growler, the day began as it often did on patrol. Visibility had improved since the previous night, and the morning hours were spent submerged, listening. At 0413 hours, at a quiet periscope depth, the boat’s sonar picked up a formation of enemy ships. The contact was sharp and clear—three vessels bearing 240 degrees true, estimated at 8000 yards and closing. The estimated course of the targets was 090 to 110 degrees true. Their size and profile suggested something more serious than patrol boats. It looked like cruisers leaving Kiska.

Commander Howard W. Gilmore, a seasoned and sharp-eyed leader who would become a legend in the silent service, had a decision to make. The enemy was moving fast, but so was the opportunity. He came to course 160 degrees true and brought the boat up to six knots. All torpedo tubes were readied. The attack plan was on.

But almost immediately, something went wrong. One of the boats in the enemy formation wasn’t cooperating with Gilmore’s plan. It made a wide turn to port, then came about heading back toward Kiska, her angle on the bow opening to more than 90 degrees. Haze swept in across the sea, swallowing visual confirmation and making observation difficult. The periscope lenses struggled against the distortion. Growler adjusted, swung into position to intercept.

Between 0439 and 0452 hours, bearings were locked in, and it was clear that the vessels, now believed to be destroyers, not cruisers, had stopped or anchored near the harbor entrance. Growler crept in closer.

At 0455, a routine check revealed that torpedo tubes 3 and 4 had been flooded for too long. Gilmore, not one to risk faulty equipment, ordered them blown dry and the fish pulled back for inspection. A quick check and reloading confirmed they were dry and ready. Time was ticking.

By 0522 hours, the sonar team called it, these were definitely destroyers. Three of them. Sharp, fast, and deadly. Gilmore’s approach was deliberate. At 0539, he maneuvered in at slow speed, silent running engaged, scanning for signs the enemy might detect them. They didn’t. The destroyers were sitting unaware in the water, likely thinking themselves safe inside their occupied harbor.

Growler moved into striking range. Two torpedoes, armed with heavy warheads, were fired at the first two targets between 0555 and 0600. Both found their mark amidships. The explosions rocked the morning calm and sent up pillars of water and fire.

The third destroyer wasn’t idle. At 0600, she fired a spread of torpedoes back, aiming between Growler’s masts. One missed. The second struck under the foremast of the destroyer herself, an accidental self-inflicted wound or perhaps a malfunction. Either way, it was chaos.

By 0600 and a half, Growler ordered depth 100 feet. Moments later, a fourth torpedo struck the third destroyer under the foremast. Flames erupted. The scene was a maelstrom.

The enemy response was swift but disorganized. Torpedoes swished past Growler, close enough to be heard by ear and on sonar. Gilmore swung the boat hard to port, trying to put distance between the submarine and the destroyers, now engulfed in smoke and flame. The pressure wave from the multiple detonations slammed into the hull. Three major explosions and over 50 secondary blasts sent Growler rolling in the depths. Instruments shook. Men braced against bulkheads. But the boat held.

Gilmore had planned to stay near periscope depth to assess the damage and gather intelligence. That plan went out the torpedo tube. The enemy, though heavily damaged, was now awake and angry. Screws from the third destroyer were heard for two minutes, then ceased. Silence returned to the sound room. No more propeller signatures. The enemy destroyer was likely sinking.

The torpedo counterattack had robbed Gilmore of the initiative. The boat dove deep to avoid further engagement. Explosions continued around them. The underwater disturbances made sonar nearly useless, and good listening was impossible. Gilmore chose to increase depth and retire, pushing Growler toward safer waters.

At 0615, sonar reported new screws astern, another patrol vessel, bearing 240 degrees true. The contact was maintained, but no pings were heard. It appeared the vessel was unaware. Suddenly, bombs dropped to starboard. Two heavy explosions rolled through the water, estimated at 500 yards distance. Likely a plane had spotted them or guessed their position. Growler had just been reminded how vulnerable a sub could be, even in a successful attack.

At 0646, Gilmore ordered a cautious return to periscope depth. The number two periscope jammed at 45 feet. The violent jolts from earlier detonations had rattled the handles out of position. They’d wedged against the well, locking the scope. A hard lesson in how every mechanical system aboard a sub had to be double-checked after action.

At 0647, a Japanese floatplane came into view, bearing 090 degrees, one mile off, altitude 300 feet. Gilmore took no chances. He ordered the boat back down to 200 feet.

Later that morning, at 0724, another periscope observation was attempted. A large column of smoke still billowed from the site of the attack, but poor visibility and shoreline background made clear identification impossible. No enemy ships were seen afloat. Gilmore chose to retire north.

By 0817, yet another floatplane circled overhead, bearing 203 degrees. The enemy was clearly hunting. Growler remained hidden below.

At 1135, the submarine surfaced. Gilmore ordered a fast run north to clear the area and assess the damage. Inspection revealed no serious harm, other than damage to the JK sound gear and the periscope mechanism. Both were still usable, though impaired.

That afternoon, Growler turned her course back toward Kiska. She had struck hard and gotten away, but the risk had been immense. Later reports would confirm the results, enemy destroyers heavily damaged or destroyed. The Aleutian campaign was still young, and the Japanese were not going to let go of Kiska easily. But Growler’s July 5 action proved that even in the cold waters off a distant island, the steel resolve of a U.S. submarine and her crew could strike fear and confusion deep into the heart of the Imperial Navy.

National Archives and Records Administration. Deck Logs of USS Growler (SS-215), July 1942. RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Entry P118. College Park, MD: National Archives.

USS Growler’s History:

Postlogue

We’ve been talking a bit about the May Incident and whether it actually happened, and how it has become an article of faith in the submarine fleet about “silence” about operations.

This article appeared in the Scranton, PA Herald on July 7, 1942…. just two days after the attack by Growler

Leave a comment