On June 24, 1948, readers of The North Adams Transcript opened their paper to find a quiet notice tucked amid the day’s dispatches: the old submarine Sailfish had been sold for scrap. No fanfare, no ceremony. Just a line confirming that one of the most storied submarines in American naval history had reached her end. To most readers, it might have meant little. But to those who knew her story—those who had followed her transformation from the sunken Squalus to the battle-hardened Sailfish—it marked the closing chapter of a saga that began with tragedy, rose through heroism, and sailed deep into the waters of legend.

Some stories in naval history read like fiction. The saga of USS Squalus and her second life as USS Sailfish is one of those rare tales. It begins with a catastrophe, moves through one of the greatest submarine rescues in American history, and ends with a battle-hardened boat that took the fight to the enemy and earned her place among the legends of the Silent Service.

Squalus was launched in 1938 from the Portsmouth Navy Yard. She was a Sargo-class submarine, among the most modern and capable in the fleet. She looked sleek, reliable, and full of promise. But that promise nearly ended before it began. On May 23, 1939, during a routine test dive off the New Hampshire coast, a catastrophic valve failure sent seawater flooding into her engine rooms. The boat plunged to the bottom and settled 240 feet below the surface.

Twenty-six men died almost instantly in the aft compartments. Thirty-three more survived in the forward section, clinging to life with what little oxygen remained. It was the nightmare every submariner feared.

What followed was a miracle of American ingenuity and courage. Commander Charles “Swede” Momsen, who had long championed submarine rescue methods, led the effort to save the survivors. The McCann Rescue Chamber, a diving bell that had never been used in a real emergency, was lowered into the deep and brought up the men in small groups. Against all odds, every one of the survivors was saved. It was the first successful rescue of men from a sunken submarine in history.

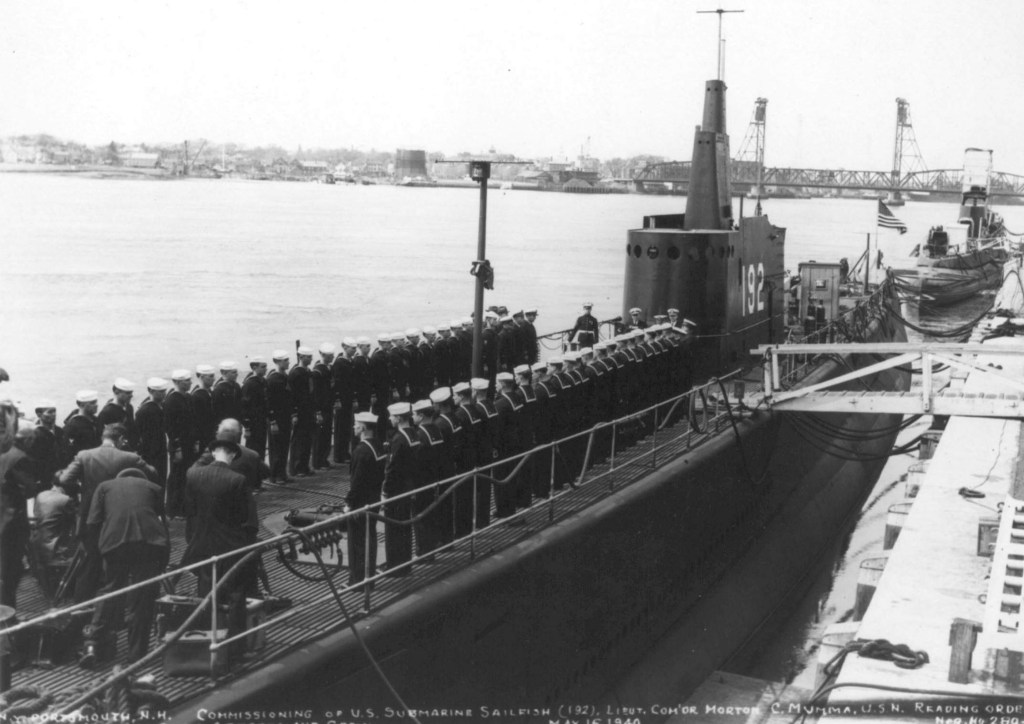

Squalus herself was not left to rust on the seafloor. Over the summer and fall of 1939, Navy salvage crews raised her and brought her back to Portsmouth. After a complete overhaul, she was recommissioned in May 1940 under a new name. Now she would be known as USS Sailfish. The name change was meant to cast off the shadow of the disaster, but the steel and soul of the boat remained the same.

Sailfish joined the Pacific Fleet in early 1941 and was operating out of Manila when the Japanese launched their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. In the chaotic opening weeks of the war, Sailfish set out on her first war patrol, tasked with harassing Japanese shipping near Luzon. The waters were filled with enemy ships, and American subs had to learn on the fly how to fight a new kind of war.

In her second patrol, Sailfish attacked a Myoko-class Japanese cruiser. She managed to get her torpedoes off and then endured a prolonged and brutal depth charge attack. The boat was shaken badly but survived and slipped away. By the time she reached Fremantle, the crew was exhausted but battle-tested. They had stared death in the face and were ready for more.

Over the course of twelve war patrols, Sailfish made her mark across the Pacific. She worked the shipping lanes of the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the Luzon Strait, and around Formosa. She disrupted enemy convoys and attacked everything from transports to cargo ships. Her kill record grew steadily. In February 1942, she torpedoed and sank the Kamogawa Maru, a Japanese army transport. The loss of that ship and its 300-plus passengers dealt a blow to Japanese logistics.

But Sailfish’s most famous moment came in December 1943. While patrolling in the Philippine Sea, she made radar contact with a convoy that included the escort carrier Chūyō. Sailfish stalked the group through bad weather, dodged patrols, and managed to fire a full spread of torpedoes into the carrier. The Chūyō went down with heavy loss of life. It was one of only a handful of enemy carriers sunk by American submarines during the war.

The victory was bittersweet. Unknown to the crew at the time, the carrier had been transporting American prisoners of war, including survivors from USS Sculpin. Sailfish had once tried to rendezvous with Sculpin before it was lost. Now, through a cruel twist of fate, she had sunk the ship carrying her fellow submariners. The news hit the crew hard when it was revealed later, but it did not tarnish their accomplishment. Sailfish had done her duty and carried out her orders. In war, the enemy does not carry flags declaring who is aboard.

Sailfish kept patrolling into 1944 and 1945. Her later missions included reconnaissance, lifeguard duties for downed airmen, and special operations work. Though enemy shipping had decreased due to earlier American submarine success, Sailfish continued to be an active and aggressive hunter. Her crews remained sharp. They knew they were riding a boat that had been to the bottom once already, and they didn’t take anything for granted.

In total, Sailfish was credited with sinking over 21,000 tons of enemy shipping. She received nine battle stars for her wartime service and a Presidential Unit Citation for extraordinary heroism. She was more than just a survivor. She was a fighter.

When the war ended, Sailfish returned home. She was decommissioned in October 1945 and removed from the Naval Vessel Register shortly after. Unlike many of her sister boats, she was not scrapped entirely. Her conning tower was saved and now stands on display at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. Visitors can see the spot where her lookouts once scanned the sea and reflect on the long journey of the boat that refused to die.

The story of Squalus and Sailfish is about more than machinery. It is about the resilience of the men who serve under conditions most people can’t even imagine. It is about overcoming disaster, learning from mistakes, and returning stronger than before. It is about what happens when courage is backed by skill and when belief in the mission is stronger than fear of the unknown.

Sailfish was born in tragedy but forged in fire. Her story belongs not just to the Navy, but to the country. She reminded us that what sinks can rise again, and that the will to fight is sometimes strongest in those who’ve already been to the bottom.

Leave a comment