She slipped beneath the waves with purpose and silence — a steel hunter in a sea of shadows. The USS Pickerel (SS-177) was no ordinary predator. She was a Porpoise-class submarine, forged in peacetime but baptized by war. And in the spring of 1943, she became the first U.S. submarine lost in the Central Pacific — vanishing without a trace in the cold, contested waters off Japan’s northern coast.

Submarines, by their very nature, dwell in mystery — machines built for stealth, crewed by men whose courage was matched only by their invisibility. The Pickerel was one such vessel. Designed in the mid-1930s as the United States grappled with the shifting tides of global politics, she was a product of the interwar Navy’s evolution — faster, longer-ranged, and more deadly than her predecessors.

She was built in Groton, Connecticut, slid into the water in 1936, and by 1937 she was prowling the Pacific. When war erupted following Pearl Harbor, Pickerel was ready. From the waters of Indochina to the cold lanes of the Kuriles, she engaged enemy shipping with silent fury. Before her final patrol, she had sunk multiple enemy vessels and earned three battle stars.

And then, silence.

Some say she was sunk by a barrage of Japanese depth charges. Others believe she struck a mine, or limped on past April 3 only to strike again before being lost. Japanese records offer ambiguity. American records offer hope, then heartbreak.

The USS Pickerel (SS-177) bore a name as sharp and swift as the predator for which she was christened. A pickerel is a small, freshwater pike — nimble, aggressive, and an apex hunter in its quiet domain. It was a fitting name for a vessel designed to strike unseen beneath the waves. She was the first U.S. Navy vessel to carry the name Pickerel, and she would carry it with pride into hostile waters.

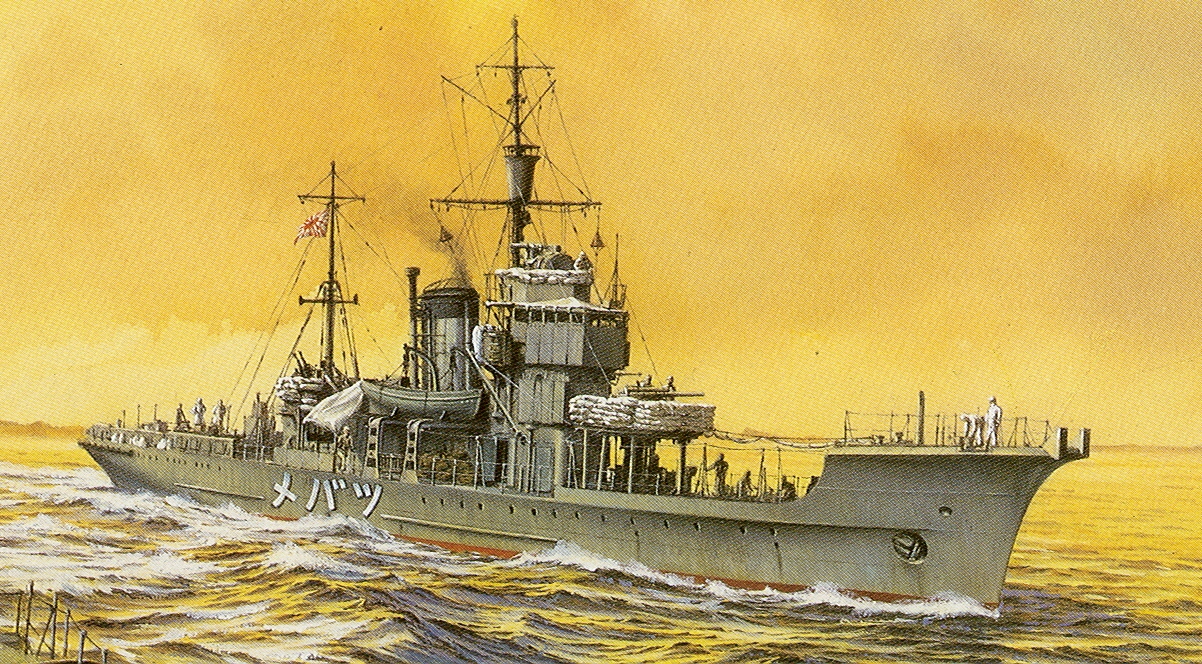

Naval naming conventions in the interwar years often favored fish and sea creatures for submarines, and the Pickerel joined a growing fleet of Porpoise-class boats that marked the Navy’s transition from experimental diving machines into serious instruments of war.

The Pickerel belonged to the Porpoise-class — a revolutionary leap forward in American submarine design. At 300 feet long with a beam of just over 25 feet, she displaced 1,350 tons on the surface and nearly 2,000 submerged. She drew about 15 feet of water, a sleek profile suited for slipping through coastal shallows or the deep Pacific.

She carried the teeth of her namesake: six 21-inch torpedo tubes (four forward, two aft) with 16 torpedoes in total, plus a 4-inch deck gun for surface action. Later, two external bow tubes were added during her 1942 updates, and she bristled with .30 caliber machine guns for anti-aircraft defense — modest by surface ship standards, but formidable for a submarine operating in stealth.

Beneath the hull, Pickerel was a marvel of diesel-electric engineering. She was powered on the surface by four Winton Model 16-201A 16-cylinder diesel engines, each generating 1,300 horsepower. Submerged, she ran silent on electric motors charged by 120-cell Gould batteries. This system allowed her to cruise for 11,000 nautical miles at 10 knots on the surface. Submerged endurance was roughly 10 hours at 5 knots — enough to evade, strike, and vanish.

Her test depth was 250 feet — shallow by today’s standards, but standard for the era. Within the tight confines of her steel skin, 5 officers and 45 enlisted men lived, fought, and operated as one.

The 1937 Booklet of General Plans reveals her inner structure in exacting detail — from the platform deck and outboard profile to the arrangement of torpedo rooms, crew quarters, and vital machinery spaces. Every inch of her hull was accounted for, designed with discipline, and built with care for a war that, at the time of her construction, had not yet begun.

Pickerel was built by the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut — the cradle of American undersea warfare. Her keel was laid down on March 25, 1935, a time when the world was still uneasily navigating the aftermath of World War I. She was launched on July 7, 1936, and sponsored by Miss Evelyn Standley, daughter of Rear Admiral William Standley, then acting Secretary of the Navy. Commissioning followed on January 26, 1937, under the command of Lieutenant Leon J. Huffman.

From Groton, the Pickerel joined a quiet fleet that would soon become legendary — and from her first rivet to her last patrol, she was destined for the depths.

After her commissioning in January 1937, USS Pickerel emerged from Groton as a lean, capable predator-in-training. The Navy wasted no time preparing her for future conflict, even if no one could quite predict when or where that conflict might come. Her first months were spent conducting shakedown operations out of New London, Connecticut — trial runs, training exercises, and readiness evaluations that honed her crew’s proficiency with every valve, periscope, and torpedo tube onboard.

In October 1937, she transited the Panama Canal en route to join the Pacific Fleet. Her voyage southward through Guantánamo Bay, then westward through the canal’s massive locks, symbolized a quiet shift in American naval focus — from the Atlantic’s memory of the last war to the growing tension brewing across the Pacific.

Operating out of San Diego and later Pearl Harbor, the Pickerel began refining the tactics of underwater warfare. She dove and surfaced across Hawaiian waters, practiced simulated attacks against surface ships, and tested the limits of her endurance. She was a schoolhouse and a proving ground all at once — for both the boat and the men who would serve aboard her.

Eventually, Pickerel was transferred to the Asiatic Fleet and stationed in the Philippines — a critical outpost of American naval power in the western Pacific. Here, war was no longer a distant speculation. By the late 1930s, Japan’s expansion across Asia had grown more aggressive, and every American boat in the region understood that drills could become real engagements at any moment.

The training intensified. The stakes rose. And on December 7, 1941, the waiting ended.

When news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reached the Pickerel, she was already poised for action. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Barton E. Bacon, Jr., she departed immediately for her first wartime patrol off the coast of French Indochina. From that moment on, she was at war — and she would never again know peacetime waters.

When the USS Pickerel began her wartime service in December 1941, the United States Navy was scrambling to regroup in the wake of Pearl Harbor. The submarine force, long considered a sideshow in naval strategy, now found itself at the forefront of America’s response. With the surface fleet wounded and Japanese forces advancing, undersea warfare became the spearpoint of resistance — and Pickerel was among the first to strike.

First Patrol – December 1941 to January 1942

Under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Barton E. Bacon, Jr., Pickerel’s first war patrol took her to the waters off Cam Ranh Bay and Tourane Harbor in French Indochina. It was a hunt that yielded frustration — a Japanese submarine and destroyer were tracked, but lost in haze and squalls. On December 19, she loosed five torpedoes at a patrol craft and missed. The patrol ended without confirmed hits but sharpened the crew’s resolve and gave them their first taste of live wartime engagement.

Second Patrol – January 1942

On her second patrol, operating between Manila and Surabaya, Pickerel made her first kill: the 2,929-ton Kanko Maru, a former gunboat converted for transport. The sinking was a breakthrough moment — proof that the Pickerel could strike hard and vanish into the blue.

Third and Fourth Patrols – Early 1942

Assigned to the Malay Barrier and then back to the Philippines, Pickerel patrolled contested waters thick with enemy traffic. Yet despite multiple attacks, she failed to score confirmed kills. Whether it was faulty torpedoes — a widespread plague among early-war submarines — or evasive Japanese seamanship, the result was the same: empty torpedo tubes and missed opportunities.

Fifth Patrol – Mid 1942

In July 1942, Pickerel sailed from Brisbane, Australia to Pearl Harbor for refit, making a short patrol in the Marianas en route. She damaged a freighter during this leg, adding to her growing résumé. Though it was a partial success, this patrol was more about getting the boat and her crew ready for the next phase of the war. During this refit, Lt. Cmdr. Bacon was reassigned, and Pickerel’s executive officer, Augustus H. Alston Jr., took command — a change that would place him in the captain’s chair for her final journey.

Sixth Patrol – January to March 1943

By now, Pickerel was seasoned — and so was the enemy. Her sixth patrol took her north to the Kurile Islands, where she hunted Japanese traffic along the Tokyo-Kiska corridor. In sixteen separate attacks, she sank the Tateyama Maru, a 1,990-ton cargo ship, and two 35-ton sampans. She also damaged another freighter and several smaller craft, harassing the enemy’s logistical lines and forcing escorts to spread thin.

These successes were hard-won. The Kuriles were cold, isolated, and well-defended. Yet Pickerel‘s crew pressed on — methodical, silent, and ruthless. For these actions, she earned her third battle star.

Each patrol left the crew leaner, more precise, more bonded. Six war patrols, five confirmed kills, ten damaged ships — Pickerel had become a ghost in the enemy’s shipping lanes. Her seventh patrol would push deeper, closer to the Japanese home islands. It would also be her last.

On March 18, 1943, USS Pickerel departed Pearl Harbor for what would be her seventh war patrol. After refueling at Midway on March 22, she set course for the northeastern coast of Honshū, Japan. This was deep into hostile territory — a region dotted with naval bases, shipping routes, air patrols, and undersea mines. It was also where Pickerel, like the fish for which she was named, intended to strike from the shadows.

The orders were straightforward: conduct offensive operations until May 1, then return to Midway. As with all patrols, Pickerel was required to send a radio transmission once she came within 500 miles of the atoll. That message never came. By May 6, her silence had stretched too long. The Navy launched a series of urgent communications, then dispatched search planes along her expected return route. Nothing was found. On May 12, 1943, USS Pickerel was officially declared lost with all 74 hands.

In the postwar years, captured Japanese records hinted at Pickerel’s possible fate. On April 3, 1943 — just days after she would have arrived on station — Japanese aircraft bombed a submerged contact off Shiramuka Lighthouse on the northern tip of Honshū. Surface vessels Shiragami and Bunzan Maru then moved in and dropped 26 depth charges. An oil slick rose to the surface. There were no survivors, no wreckage — only silence and swirling oil.

While this location was slightly north of Pickerel’s assigned patrol area, no other U.S. submarines were known to be operating there at the time. It is probable, some say, that Pickerel may have ventured north in search of better hunting grounds before her doom descended.

But the story grows murkier. That same April, Japanese records credit Pickerel with sinking two enemy vessels: Submarine Chaser No. 13 on April 3, and the Fukuei Maru, a 1,113-ton cargo ship, on April 7.

If she was sunk on April 3, who then sank the Fukuei Maru four days later?

Some historians speculate that Pickerel may have survived the April 3 attack — leaking fuel, perhaps damaged — and managed to limp southward to launch one last, desperate strike. Others suggest the April 7 kill might be misattributed, or that Pickerel was indeed destroyed on April 3, and her reported posthumous kill is an error born of the fog of war and confused Japanese recordkeeping. (A special notation on the Japanese war diaries admits that records for April 1943 may be incomplete or inaccurate.)

Another possibility — albeit a less likely one — is that Pickerel struck a mine, a danger that loomed across much of Japan’s coastal defenses. However, U.S. records of her previous patrol in the same region show she generally avoided shallow water and stayed outside the 60-fathom curve — a prudent move, since mines were typically laid in shallower areas.

In the absence of wreckage or survivors, the Navy settled on the most probable cause: Pickerel was sunk by enemy depth charges. But even this conclusion comes with an asterisk. Her loss remains one of the more haunting uncertainties in the Silent Service’s long roll call of sacrifice. She vanished without a final signal, without a final report, without a known grave — a hunter lost in her own element.

Personal Story: The Loss of MoMM2 Paul T. Cynewski

Beneath the statistics of war and the steel of a submarine’s hull lies the human cost — a truth that echoed through the generations of one American family when USS Pickerel vanished. Among her crew was MoMM2 Paul T. Cynewski, a machinist’s mate and the only known war casualty in his extended family. His story, tenderly recounted by Jane Elkin in Bay Weekly, transforms a naval tragedy into a deeply personal loss.

It was Memorial Day, 1997, when Elkin’s young daughter Julia caught a pickerel from the dock behind their new Annapolis home. The fish was small, silvery, and swift — and it stirred a memory long buried in the family’s history. Paul Cynewski had been aboard the submarine that bore that fish’s name. It was the first time young Julia heard the story — the war, the disappearance, the boy who went to sea and never came home.

Paul had been 22 years old. The last anyone in the family saw of him was a brief wave from a bus station in a neighboring town, his Navy “Cracker Jack” uniform neatly pressed, his duffel slung over one shoulder. He was headed west — to his boat, to war, and ultimately into legend. His younger cousin Bill, then still in school, never forgot the moment he heard the news of Paul’s death. He was reprimanded for daydreaming in class, staring out the window, trying to make sense of something bigger than any childhood could comprehend.

On Paul’s last visit home, he was building a kayak in the basement — wood frame nearly done, canvas still to be stretched. The kayak was never finished. His brothers couldn’t bring themselves to complete it. It stood as a quiet monument in the basement, a project interrupted by war.

Years later, Julia would catch that same pickerel a second time, just five minutes after releasing it — a coincidence too strange to ignore. To the family, it felt like a sign. Maybe Paul was still watching. Maybe, in some small way, he had come home.

Paul T. Cynewski is remembered on a war memorial erected by the Polish Club in Amesbury, Massachusetts, his hometown. His name, along with those of 73 others, is etched into the collective memory of USS Pickerel’s final voyage — sailors now “Still on Patrol.”

In war, ships are often remembered for the battles they win, the enemy they sink, or the ports they take. But in the Silent Service — the brotherhood of submariners — it is often the missing that speak the loudest. USS Pickerel (SS-177), though lost in the murk of unconfirmed reports and enemy records, lives on in stone, steel, and solemn tradition.

Her name is etched among 52 others on the Submarine Memorial at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis — a torpedo-shaped monument overlooking the Severn River. There, Pickerel and her 74-man crew are listed as “Still on Patrol,” a haunting phrase used to mark those submariners who left and never returned. The phrase speaks not just of death but of eternal vigilance, of men who slipped beneath the sea and remain forever part of its currents.

The Navy did not forget them. Nor did the families.

Across the United States, in hometowns like Amesbury, Massachusetts — where Paul T. Cynewski is honored by a local Polish-American war memorial — names like Pickerel live on in quiet remembrance. In Groton, Connecticut, where she was born, her story is preserved in archives, shipbuilding records, and the memories of Electric Boat craftsmen who watched her slide into the Thames River, sleek and full of promise.

Though Pickerel’s final patrol ended in silence, her war record spoke with clarity. She earned three battle stars, sank or damaged fifteen enemy vessels, and pushed into some of the most dangerous waters of the war. Her legacy is not diminished by the lack of a wreck or an official cause of death. On the contrary — it is amplified by the mystery. Her loss reminds us of the fog of war, the bravery of her crew, and the cost of patrolling where few dared to go.

In recent years, renewed interest in lost submarines has led to efforts to locate missing boats — Pickerel among them. As technology improves, the possibility of finding her final resting place grows. But even if she remains lost to the sea, her story is not.

The USS Pickerel (SS-177) was more than steel and ordinance — she was a promise of silent resistance in the darkest moments of the Pacific War. From her careful construction in Groton to her shakedown off New London, from the warm waters of the Philippines to the icy currents of northern Japan, she sailed with purpose and peril. Her crew, seventy-four men strong, served with the quiet courage demanded of those who ride beneath the waves.

What became of her — whether she was torn apart by depth charges, swallowed by a minefield, or fought on days longer than the records say — remains unresolved. But history does not require a confirmed wreck to recognize a sacrifice. It requires only memory, and the will to speak the names of the lost.

In memorials carved from granite, in old family photos, in stories passed at dinner tables or whispered on docksides, Pickerel endures. She lives in the honor roll of American submarines, in the traditions of the Navy, and in the quiet mystery of the sea that took her.

To remember Pickerel is to remember them all — the boats that slipped away and never came back. To tell her story is to answer her silence. She is still on patrol, and always will be — until the last bell tolls and every sailor is accounted for beneath the waves.

Leave a comment