Before the sun ever rose on March 24, 1943, the USS Wahoo (SS-238) had already made a name for herself. She was not just another Gato-class submarine; she was the boat sailors whispered about with awe and admiration. Under the relentless and fearless command of Lieutenant Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton, Wahoo had become a wolf in the water—bold, cunning, and, above all, lethal. Morton had replaced “Pinky” Kennedy after two patrols of frustrating near-misses and faulty torpedoes, and from the moment he gave that now-famous talk—declaring Wahoo “expendable” and inviting any unwilling soul to walk away—her character changed.

Before the sun ever rose on March 24, 1943, the USS Wahoo (SS-238) had already made a name for herself. She was not just another Gato-class submarine; she was the boat sailors whispered about with awe and admiration. Under the relentless and fearless command of Lieutenant Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton, Wahoo had become a wolf in the water—bold, cunning, and, above all, lethal. Morton had replaced “Pinky” Kennedy after two patrols of frustrating near-misses and faulty torpedoes, and from the moment he gave that now-famous talk—declaring Wahoo “expendable” and inviting any unwilling soul to walk away—her character changed.

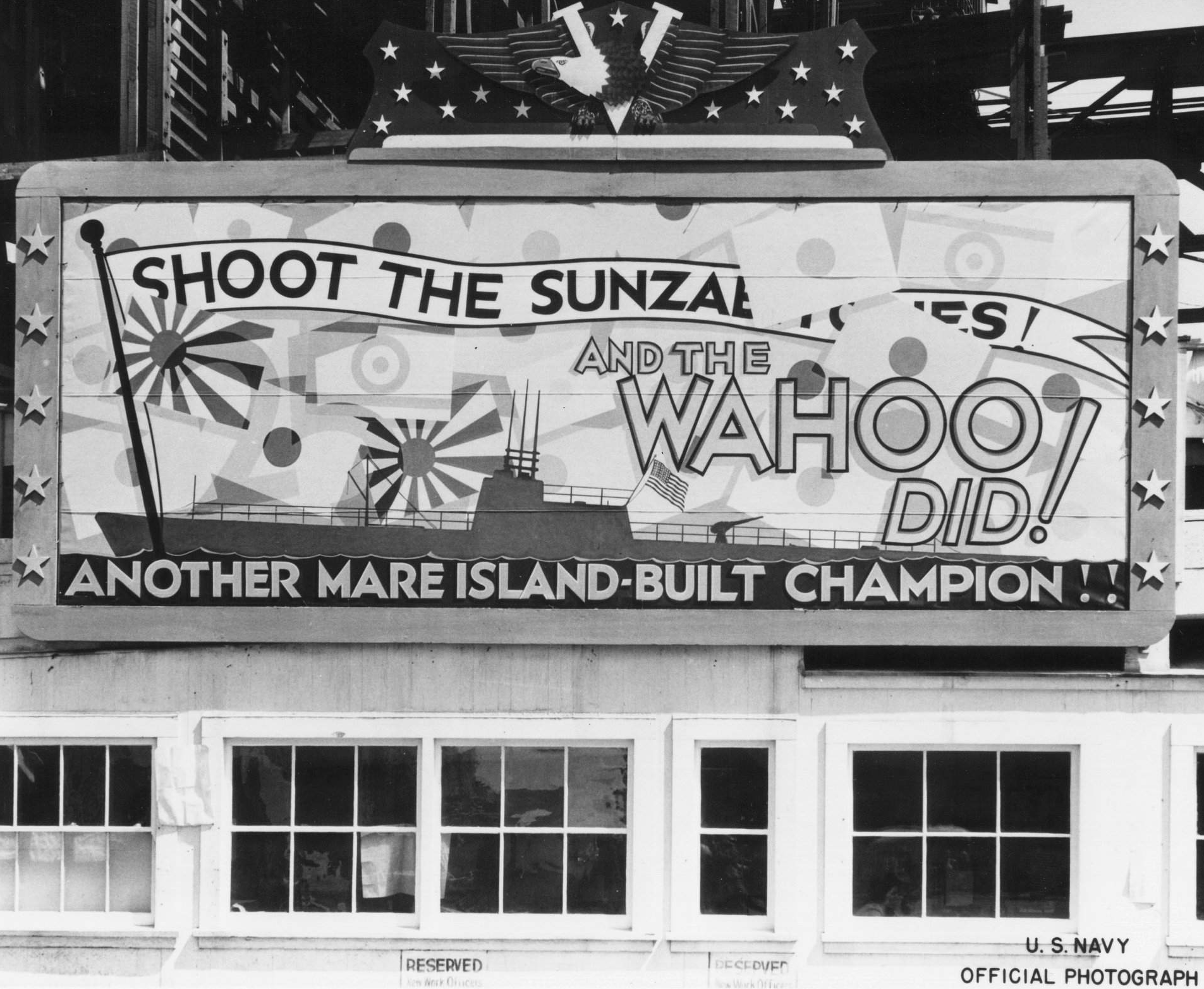

USN photo courtesy of Darryl L. Baker.(NAVSOURCE)

Morton’s first few patrols were nothing short of audacious. Alongside his sharp-eyed Executive Officer Dick O’Kane, Wahoo went on a rampage in the Solomon Sea and the Bismarck Archipelago, sinking ships, dodging destroyers, and teaching the Japanese merchant fleet to fear the unseen. By the time March 1943 rolled around, the Wahoo was already legendary. The brass in Pearl Harbor could not ignore the success, nor could the Imperial Japanese Navy. Morton’s fourth war patrol had taken the Wahoo into treacherous waters—literally uncharted territory for American submarines—the shallow, cold, and dangerous Yellow Sea, off the coasts of Korea and northern China.

That is where we pick up her story.

At 0505 on March 24, Wahoo dove beneath the chilly waters and commenced her submerged patrol. A floatplane was spotted later that morning, a reminder that eyes were in the skies, but by early afternoon, a thin thread of smoke rose above the horizon. That thread would unravel into one of the most dramatic and relentless series of engagements in the war patrol’s history.

By 1330, Morton had already determined that they would not catch the first freighter—a vessel between 4,000 and 5,000 tons—before she slipped behind the protective breakwater at Dairen. But he was not about to let the opportunity slide. Instead, he committed Wahoo to an “end run,” racing to cut off future prey along this newly discovered shipping route. He called it the “Nips’ end run route.” If Wahoo had her way, it would not be end-running anything anymore.

Just after 1920, Wahoo’s radar picked up another contact—a large tanker, later identified as the Syoyo Maru, displacing 7,499 tons and fully loaded with fuel oil. Morton maneuvered into position and, at 1949, loosed a spread of three torpedoes at a 1,700-yard range. The result? Heartbreaking. The first two exploded prematurely—classic Mark 14 behavior—and the third missed outright. He fired a fourth, and again, nothing. The tanker, now alert and armed, returned fire at 3,500 yards with Japanese flashless powder that lit the sky in fireless thunder. One shell landed directly ahead of Wahoo. She dove hard, evaded, and tracked.

Fourteen tense minutes later, Wahoo surfaced again. She sprinted to gain a forward position and at 2054, dove and made ready for a second attack. By 2122, Morton fired another spread—this time with TNT warheads—and one struck true, punching into the engine room. The Syoyo Maru sank in just over four minutes, burning as she went down. Fuel oil spilled across the surface, and the night burned like day.

But Morton and the Wahoo were not done. Not by a long shot.

In the early hours of March 25, just before 0200, Wahoo spotted another ship running with a green light—likely her starboard running light. With the radar temporarily out of action, Morton relied on moonlight and the Mark I eyeball. He maneuvered for position, dove at 0355, and launched two torpedoes at 0436 at a medium-sized freighter, later identified as Sinsei Maru (2,556 tons). Once again, both torpedoes exploded prematurely—one at 26 seconds, the other at 49. The crew’s frustration must have been palpable.

So Morton made a call. One that perfectly defined his leadership: he ordered Battle Surface.

At 0444, Wahoo broke the surface and opened fire. Her very first 4-inch shell slammed into the after deckhouse at 3,800 yards. She closed the range, raked the ship with 20mm fire, and peppered her with ninety 4-inch shells. The Sinsei Maru caught fire and listed hard. As they passed survivors clinging to debris and calling out, the crew of the Wahoo, perhaps with gallows humor or maybe weary compassion, called out, “So solly, please.”

They left the freighter burning and turned to a new contact. Just after 0510, a lookout spotted a small diesel-driven cargo ship—possibly the Hadachi Maru, about 1,000 tons. Wahoo opened up with everything she had: 20mm and 4-inch rounds, lighting up the morning like it was the Fourth of July. The Japanese ship tried to ram, pushing up to 13 knots. At one point, a crewman in the crow’s nest waved his arms wildly until gunfire sent him sliding down a guy wire like a startled cat. Wahoo pounded her until she was blazing stem to stern and dead in the water.

Two major surface engagements before breakfast. That was the Wahoo.

USN photo courtesy of Darryl L. Baker. (NAVSOURCE)

When we reflect on those two brutal days in March 1943, we are reminded not just of the boldness of American submariners—but also of the terrible costs of war. The phrase “So solly, please” was likely said half in jest, half in grim resignation. It captures the human contradiction that is submarine warfare: courage wrapped in steel, humor laced with horror. The crew of the Wahoo did their duty—and did it well—but they were not immune to the heavy hearts that sometimes followed a successful kill.

And then came the silence.

Just a few months later, in October 1943, Wahoo disappeared on patrol in the La Pérouse Strait. Japanese records later confirmed her sinking by aircraft and surface vessels. She was lost with all 80 souls aboard. No survivors. No last transmission. Just… silence. Wahoo was stricken from the Navy list in December. But her memory? That was never erased.

Today, Wahoo is remembered not just as a predator, but as a symbol of unyielding American spirit. She went where no submarine had gone. She fought with fire and wit. She challenged faulty torpedoes, shallow waters, and armed convoys. And she inspired every submariner who followed in her wake.

She was bold. She was deadly. She was expendable—but never forgotten.

Sailors, rest your oars.

Leave a comment