The final days of 1941 were a grim chapter for the United States Navy. The devastating attack on Pearl Harbor had left the Pacific Fleet crippled, with eight battleships sunk or heavily damaged, three cruisers and four destroyers similarly incapacitated, and over 2,400 Americans killed. The harbor’s waters, once bustling with activity, were now a murky graveyard of oil-slicked wreckage. The Navy’s confidence was shaken, and the American public demanded leadership that could reverse the tide of despair.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, understood the enormity of the challenge. The Pacific Fleet needed a commander who could not only rebuild its strength but also restore its fighting spirit. Chester W. Nimitz, a rear admiral known for his expertise in submarines and diesel propulsion, was an unconventional but inspired choice. Calm, pragmatic, and forward-thinking, Nimitz had quietly built a reputation as a problem-solver who excelled under pressure. Yet, his appointment leapfrogged dozens of more senior officers, sparking controversy within Navy ranks. Roosevelt, however, had faith that Nimitz was the man for the job, and history would soon vindicate that belief.

Nimitz arrived in Hawaii on Christmas Day after a grueling seven-day journey by train and aircraft. The sight that greeted him was sobering. Battleships lay in shallow graves, their superstructures twisted and blackened, while Pearl Harbor itself still bore the scars of the Japanese attack. Despite the devastation, Nimitz exuded confidence. Quietly, he remarked to his wife Catherine that the attack could have been worse. Had the battleships been sunk in deep water, they might have been irrecoverable. Most, he believed, could be raised and repaired. It was a testament to his ability to find opportunity even in the bleakest circumstances.

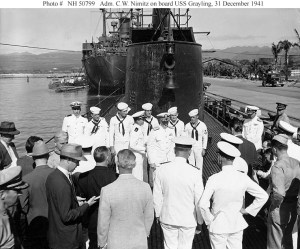

The ceremony to transfer command of the Pacific Fleet was held on December 31, 1941, not aboard a battleship, as tradition dictated, but on the deck of the USS Grayling, a Tambor-class submarine. This choice was both practical and symbolic. The fleet’s battleships were out of commission, and submarines like Grayling represented the Navy’s best hope for striking back in the early months of the war. The morning was subdued, the usual New Year’s Eve festivities replaced by a sense of solemn determination. Senior officers, sailors, and a few civilians gathered on the submarine’s deck, aware that they were witnessing a pivotal moment in history.

Nimitz stood tall on Grayling’s deck, his demeanor calm and resolute. He officially relieved Vice Admiral William S. Pye, who had been serving as acting commander since Admiral Husband E. Kimmel’s removal earlier that month. The ceremony was simple yet deeply significant. As Nimitz hoisted his flag, signaling his assumption of command, the assembled crowd broke into applause. It was a moment of renewed hope, a signal that the Pacific Fleet, battered but unbroken, was preparing to reclaim the initiative.

After the formalities, Nimitz addressed the gathered officers and crew. His words were deliberate, balancing acknowledgment of the challenges ahead with confidence in ultimate victory. “We have taken a tremendous wallop,” he admitted, “but I have no doubt of the ultimate outcome.” He urged patience and precision, emphasizing the importance of striking when the time was right. “Bide your time, keep your powder dry, and take advantage of the opportunity when it’s offered,” he said. These words, measured yet inspiring, set the tone for the Navy’s strategy in the difficult months to come.

Following his speech, Nimitz presented awards to several sailors and aviators who had distinguished themselves in the chaotic early days of the war. Among them was Ensign F.M. Fisler, who received the Navy Cross for heroism. These awards served as reminders of the bravery and sacrifice that would be required in the long road to victory.

Others receiving awards, standing left-to-right in line behind Nimitz and Fisler, are: Ensign C.F. Gimber, USNR; AMM1c L.H. Wagoner (also awarded the Navy Cross); AMM1c W.B. Watson; R3c H.C. Cupps; R2c W.W. Warlick and AMM2c C.C. Forbes. They were the crew of a Navy bomber. Pelias (AS-14) is in the background. (NAVSOURCE)

The USS Grayling, too, played a role in this critical moment. Just five days after hosting the change of command, the submarine departed on its first war patrol, a reconnaissance mission in the Northern Gilbert Islands. Grayling’s service during the war was remarkable, completing eight patrols, sinking over 20,000 tons of enemy shipping, and earning six battle stars. Tragically, her story ended in September 1943 when she was lost with all hands, but her legacy as a symbol of resilience and determination lived on.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s assumption of command marked a turning point for the Pacific Fleet and the broader Allied effort in the Pacific. His leadership, characterized by humility, pragmatism, and unwavering resolve, quickly restored morale and laid the groundwork for a string of iconic victories. Under his command, the Navy transitioned from a defensive posture to an aggressive and calculated offensive strategy. Within months, Nimitz would oversee critical battles, including the pivotal victory at Midway, which shifted the balance of power in the Pacific.

The decision to hold the ceremony aboard a submarine underscored the Navy’s adaptability and determination. Submarines like Grayling, while not the centerpiece of traditional naval power, became vital tools in the early war effort, conducting reconnaissance and disrupting Japanese supply lines. By choosing Grayling for his flag, Nimitz sent a powerful message: the Navy’s fighting spirit remained intact, and its capacity for innovation would drive its resurgence.

In the broader context of the Pacific War, Nimitz’s leadership was transformative. He not only rebuilt the fleet but also inspired a sense of unity and purpose that carried the Navy through its darkest hours. By the end of the war, the Pacific Fleet had grown into the most formidable naval force in history, delivering the decisive blows that brought Imperial Japan to its knees.

The events of December 31, 1941, aboard USS Grayling serve as a testament to the power of leadership, resilience, and unity. In the face of overwhelming adversity, Nimitz charted a course to victory, proving that even in the darkest moments, hope and determination can prevail. It was aboard that unassuming submarine that the tide of war began to turn, setting the stage for the United States Navy’s long and triumphant road to victory.

Leave a comment