A Personal Observation

In the middle of Patrol 5, around late October of 1984, I was handed a paperback copy of “The Hunt for Red October.” It was not required reading, but many of the folks aboard who had already read it were effusive in their praise for it. They assured me that it would “help” with the final days of my ships quals, which were quickly coming to completion.

In the middle of Patrol 5, around late October of 1984, I was handed a paperback copy of “The Hunt for Red October.” It was not required reading, but many of the folks aboard who had already read it were effusive in their praise for it. They assured me that it would “help” with the final days of my ships quals, which were quickly coming to completion.

As I recall, it did not provide any specific assistance in my final quals and my board. What it did do was open my eyes to the open discussion of things that I, at least to that point, believed were never to be discussed. Not even the idea that there might be something – anything whatsoever – to even discuss.

A couple of years later, I visited Crown Books (as it was then) at the Tacoma Mall shopping Center. On the night before we would leave for another patrol, I purchased Red Storm Rising, another in the run of books by Tom Clancy that seemed – at least on the surface (so to speak) to openly discuss things that I still believed and accepted should not only not be discussed, but never would be discussed. I suppose that the argument at the time was that the books were works of fiction that just managed to sound authoritative.

Seven years after I had left the Navy, I had relocated to Modesto, CA, when I saw on the counter at the local bookstore, a copy of Blind Man’s Bluff, by Sharon Sontag and Christopher and Annete Drew. They were not names that I recognized, and frankly, I had no clue who they were. But as the Tom Clancy books were continuing to make millions, I presumed that this too, was just a sensationalistic attempt to impress the public with fanciful stories and outrageous claims.

I think that today, we see all of this… differently? Even John Pina Craven would go on to admit in his book Silent War, that his first reaction to The Hunt for Red October was to wonder who leaked the story to Tom Clancy[1]?

In an era when we now take for granted the “SpySub” mythos, from Halibut, to Seawolf, to Parche to Jimmy Carter and others, it was something of a refreshing moment to learn that the term “SpyRon” referring to submarines and their operations, wasn’t anything new or even birthed in the Cold War. In fact, it was started in the early months of the Pacific war when three US Submarines, and a few others thrown in for good measure, were organized loosely into a squadron that would be tasked with conducting operations that would make the Cold War look mild.

While there were many Spyron missions, the most famous of which involved Nautilus and the Makin Island raid, and Trout with her cargo of gold, the truth is that there were most than one hundred and sixty assigned Spyron missions. So many, that the Fleet and Squadron Commanders would complain about them to the Pentagon as the missions were dragging boats away from the primary mission of interdicting Japanese shipping. The complaints fell on deaf ears, and the Spyron missions continued throughout the war, although it would be fair to say that the most important and critical and most organized of these would fall in the 1943-44.

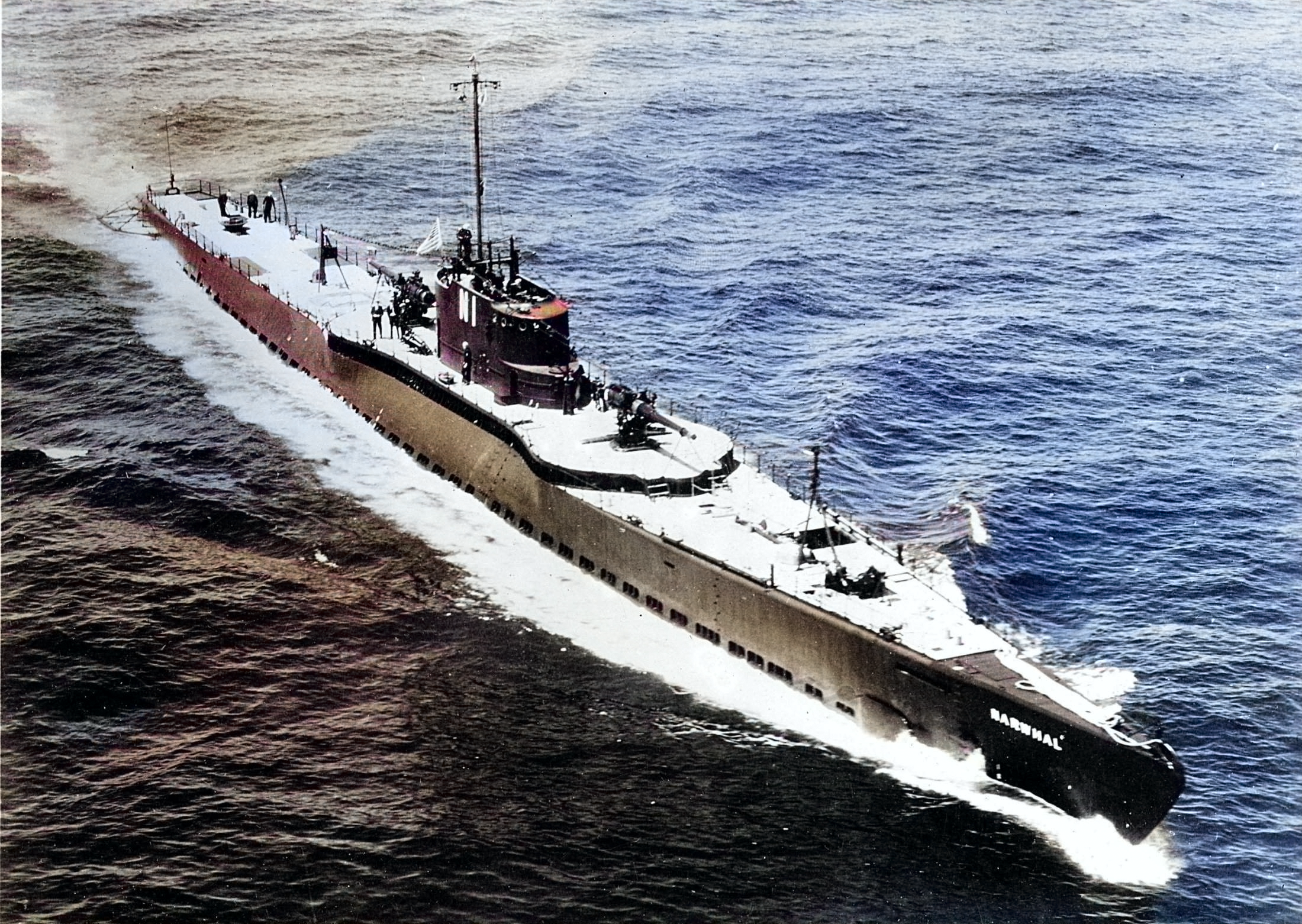

As 1943 ended, the Spyron boat, Narwal, was making her way through the Philippines. Here and there she would unload cargo needed by the guerilla fighters still opposing the Japanese occupation, and picking up those who needed to leave…

The Silent Lifeline: U.S. Navy “Spyron” Submarine Missions in World War II

World War II was a conflict defined by bold strategy and relentless innovation, with battles fought not only in trenches and open seas but also in the shadows of covert operations. Among the unsung heroes of the Pacific Theater were the submarines of the U.S. Navy’s Silent Service, whose missions under the codename “Spyron” became lifelines for Filipino guerrillas and civilians trapped behind enemy lines.

Spyron—short for “Submarine Spy Squadron”—was a daring initiative that provided weapons, supplies, and hope to resistance forces in Japanese-occupied Philippines. These missions also carried out dramatic rescues, extracting key personnel and civilians from enemy-held territories. Conducted with extraordinary risk and precision, Spyron missions were not just acts of war; they were acts of humanity, showcasing the ingenuity of the Silent Service and the resilience of the Filipino people.

Setting the Stage: The Fall of the Philippines

In the opening months of the Pacific War, the Philippines fell to the Japanese in a rapid and devastating campaign. American and Filipino forces, under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, made their final stand on Bataan and Corregidor. Though they fought valiantly, surrender was inevitable. The fall of the Philippines plunged the archipelago into a brutal occupation, but it also ignited the spark of resistance.

Filipino guerrillas took to the mountains and jungles, forming networks to sabotage Japanese operations, gather intelligence, and protect civilians. Their fight was valiant but perilous, and they faced a chronic shortage of weapons, medical supplies, and food. Conventional resupply methods were impossible, given Japanese naval dominance. The U.S. Navy’s submarines became their lifeline.

The Birth of Spyron: A Covert Solution

Spyron operations began in 1943, driven by the urgent need to support the Philippine resistance. The submarines chosen for these missions were not the sleek, modern Gato-class vessels making headlines for their daring attacks. Instead, older and larger submarines like the USS Narwhal (SS-167) and USS Nautilus (SS-168) were used. These boats had the cargo capacity to carry tons of supplies and passengers, making them ideal for these unconventional missions.

One of the architects of Spyron operations was Lieutenant Commander Charles “Chick” Parsons, a former naval officer and businessman who had lived in the Philippines before the war. Fluent in Tagalog and deeply familiar with the geography, Parsons became the vital link between the U.S. Navy and Filipino guerrillas. Risking his life, he coordinated supply drops, scouted landing sites, and ensured the survival of the resistance movement.

The Missions: Deliveries and Daring Rescues

Spyron missions often followed a dangerous pattern. Submarines would depart from Allied bases in Australia or New Guinea, loaded with rifles, grenades, medical kits, food, and radio equipment. They would then navigate the treacherous waters of the Philippine archipelago, dodging Japanese patrols and minefields to reach their drop points.

Rescuing the DeVries Family (USS Narwhal)

One of the most poignant Spyron missions took place on December 5, 1943, when the USS Narwhal, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Frank D. Latta, rescued the DeVries family from Japanese-occupied Mindanao. The family, Dutch civilians hiding in the jungle, had been evading Japanese forces for months. The Narwhal surfaced off the coast of Alubijid, Misamis Oriental, under cover of darkness. Guerrillas ferried the DeVries family and other evacuees—men, women, and children—to the submarine in small boats. The operation was conducted with absolute stealth, ensuring the safety of all aboard.

One of the most poignant Spyron missions took place on December 5, 1943, when the USS Narwhal, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Frank D. Latta, rescued the DeVries family from Japanese-occupied Mindanao. The family, Dutch civilians hiding in the jungle, had been evading Japanese forces for months. The Narwhal surfaced off the coast of Alubijid, Misamis Oriental, under cover of darkness. Guerrillas ferried the DeVries family and other evacuees—men, women, and children—to the submarine in small boats. The operation was conducted with absolute stealth, ensuring the safety of all aboard.

This mission, like so many others, exemplified the dual role of Spyron missions: sustaining resistance efforts while offering a lifeline to those in peril.

Supplying Guerrillas and Gathering Intelligence

The USS Nautilus and Narwhal conducted multiple missions to deliver supplies and evacuate key individuals. On one notable mission, Narwhal transported Lieutenant Commander Parsons after he had coordinated critical intelligence operations with guerrillas. Submarines also carried out reconnaissance, collecting information on Japanese troop movements and fortifications, which proved invaluable for Allied planning.

Cultural Context: Collaboration and Camaraderie

The success of Spyron missions depended on the close collaboration between the submarines and Filipino guerrillas. Communication was fraught with danger; a single intercepted radio transmission could expose an operation. Yet the guerrillas persevered, using their intimate knowledge of the terrain to secure landing sites and protect the submarines from discovery.

For the submariners, these missions were a departure from their typical combat roles. They became lifelines for resistance fighters and civilians, carrying not just supplies but also the hope of liberation. The camaraderie between the crews and the guerrillas was born out of shared danger and a common cause, creating bonds that transcended the war.

Turning Points and Triumphs

As the Allied forces prepared for the liberation of the Philippines in 1944, Spyron missions reached their zenith. Submarines delivered weapons and food to guerrillas who would later provide critical intelligence and harass Japanese forces ahead of major battles like Leyte Gulf. The efforts of Spyron helped weaken Japanese control of the islands, paving the way for MacArthur’s triumphant return.

Reflections and Legacy

The Spyron missions were a remarkable blend of ingenuity, courage, and compassion. They demonstrated the versatility of submarines, which served not only as instruments of destruction but also as lifelines for those fighting for freedom. These missions blurred the lines between conventional warfare and clandestine operations, highlighting the adaptability of the U.S. Navy’s Silent Service.

For the Filipino guerrillas, the submarines symbolized hope and resilience. The supplies they delivered sustained not only the physical fight but also the spirit of resistance. The bravery of the guerrillas, combined with the skill of the submariners, created a partnership that was vital to the Allied war effort in the Pacific.

Today, Spyron missions are remembered as one of the most unique and inspiring chapters of World War II. They exemplify the ingenuity and determination that defined the fight against tyranny. The legacy of these missions lives on in the stories of those who fought, those who were rescued, and those who gave everything in the pursuit of liberty.

[1] To be clear, there was no Red October Submarine story, but there WERE a series of other events that taken together, per Craven, could have been woven together in the fictional story of Red October while using highly classified information from those other events.

Leave a comment