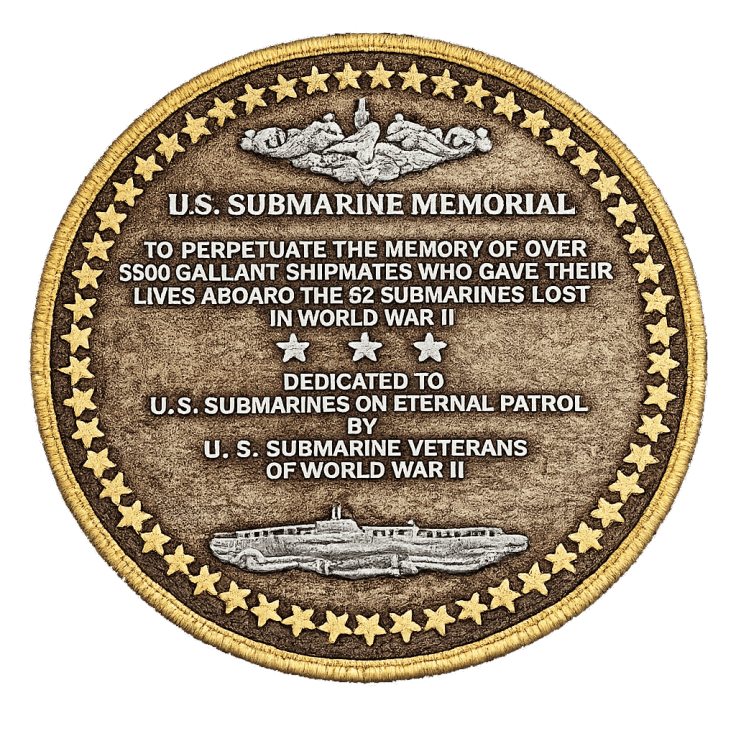

February has a way of thinning the ranks. It sits awkwardly in the calendar, shorter than it ought to be, often colder than expected, and in the war years it carried a particular weight for the men of the Silent Service. The United States Navy submarine force never occupied much physical space in the wartime Navy. Fewer than two percent of personnel wore dolphins. Yet by the end of the Pacific War, submarines had strangled more than half of Japan’s merchant shipping. That success did not come cheaply. Fifty-two boats did not return. Thirty-five hundred and six men went on what submariners still call eternal patrol. No other branch of American service lost such a high percentage of its own.

The USS Barbel (SS-316) was one of the many steel sharks that prowled the depths of the Pacific during World War II, silently hunting Japanese shipping in the vast, contested waters. She was a Balao-class submarine, designed for endurance, stealth, and lethality. At 311 feet long, armed with ten 21-inch torpedo tubes and a 5-inch deck gun, she was built to strike hard and slip away unnoticed. Commissioned in April 1944, Barbel quickly proved her worth, sinking multiple enemy vessels in her first three war patrols. But the Pacific was a dangerous hunting ground, and by early 1945, the tide of war was shifting, bringing new dangers to the Silent Service.

The USS Barbel (SS-316) was one of the many steel sharks that prowled the depths of the Pacific during World War II, silently hunting Japanese shipping in the vast, contested waters. She was a Balao-class submarine, designed for endurance, stealth, and lethality. At 311 feet long, armed with ten 21-inch torpedo tubes and a 5-inch deck gun, she was built to strike hard and slip away unnoticed. Commissioned in April 1944, Barbel quickly proved her worth, sinking multiple enemy vessels in her first three war patrols. But the Pacific was a dangerous hunting ground, and by early 1945, the tide of war was shifting, bringing new dangers to the Silent Service.