December 10 tends to sit quietly on the calendar, a date that rarely makes headlines and never asks for much. Yet, across the long and strange saga of the United States Navy Submarine Force, this ordinary wintery day has carried more weight than it lets on. It has seen explosions in cramped early hulls, the smoke of war hanging over Cavite, the long shadow of strategic deterrence, and the uneasy reality that even the most powerful navy in the world still depends on shipyards that run behind schedule and politicians who promise to fix them.

1910: A lesson written in gasoline fumes

The story begins in 1910 with the USS Grampus and her gasoline engine, which behaved about as well as gasoline engines inside steel tubes usually do. The blast that killed a crewman was the first major operational accident for the young Submarine Force. It reminded the Navy that volatile fuel and tight spaces create their own theology, one where mistakes are punished immediately. The tragedy pushed the service toward diesel engines, a safer alternative that Chester Nimitz was already championing while most people still wondered whether submarines had much of a future.

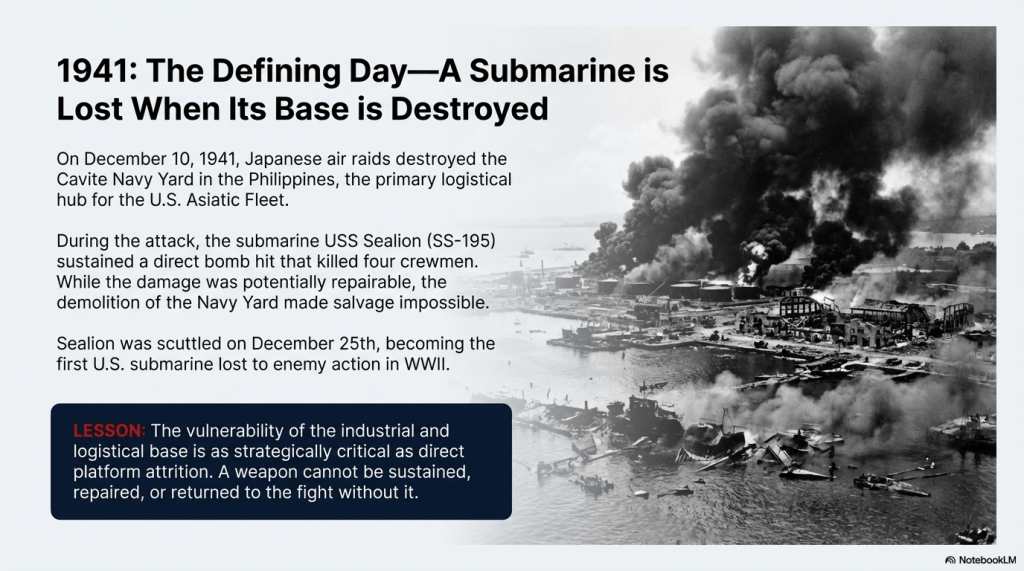

1941: War comes fast and without mercy

Thirty one years later, December 10 arrived with a devastating clarity. At Cavite, Japanese bombers turned the Navy Yard into rubble, set fires that could not be fought, and left the USS Sealion in a condition no repair party could save. Four men died in her engine spaces and another died aboard Seadragon when a bomb fragment tore through her pressure hull. These were the first American submariners killed in the war, a grim beginning for a service about to shoulder an enormous share of the Pacific fight.

Out near Hawaii, the war offered a hard counterpoint when an SBD Dauntless from the carrier Enterprise found the Japanese submarine I 70 and delivered a fatal strike. I 70 had taken part in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Her destruction marked the first Japanese combatant ship sunk in the war. The day revealed the cruel arithmetic of early conflict. Loss on one end, success on the other, both carried on the same winter wind.

1979 and 1982: The quiet power of deterrence

As the Cold War matured, December 10 took on a different shape. In 1979, the USS Francis Scott Key completed her first patrol with the new Trident I missile system. It proved that older hulls could be modernized to meet new strategic needs. In 1982, the first Ohio class submarine returned from her inaugural deterrent patrol. Ohio was huge, quiet, and built for a mission that depended on silence rather than spectacle. Her return confirmed that a new era of undersea deterrence had arrived.

2025: The promise and the problem of modern shipbuilding

Most recently, December 10 has become a reminder that even the best submarines start as unfinished steel in a shipyard that must meet deadlines it rarely keeps. Newport News Shipbuilding marked the keel laying of USS Barb, another Virginia class boat in a production line that always seems to strain at the edges. On the same date, the Secretary of the Navy announced a major investment in a new AI driven system called ShipOS. The idea is simple enough. Use modern tools to untangle decades of inefficiency and bottlenecks. In practice, it carries the scent of a familiar Navy prayer. May this time, finally, be the time the industrial base catches up with the fleet it is supposed to build.

December 10 is not a holiday. It has no special flag and no ritual observance. Yet, across more than a century of submarining, it keeps surfacing with a reminder that the past is always speaking. Sometimes in the hiss of gasoline vapor, sometimes in the thunder of bombs, sometimes in the quiet hum of a missile boat returning from patrol. And today, in the whir of algorithms that promise to fix the oldest problems in the newest ways.