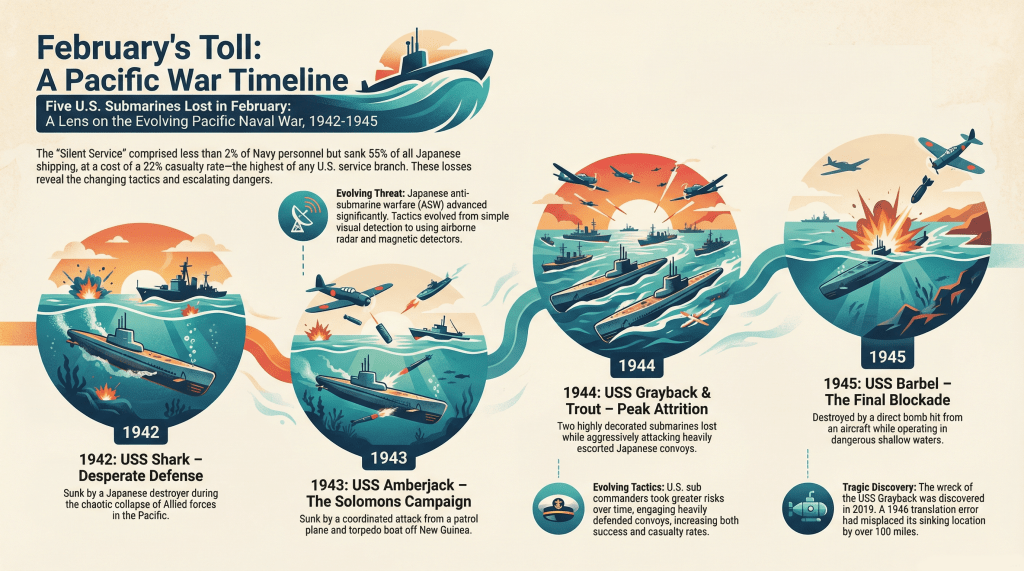

February has a way of thinning the ranks. It sits awkwardly in the calendar, shorter than it ought to be, often colder than expected, and in the war years it carried a particular weight for the men of the Silent Service. The United States Navy submarine force never occupied much physical space in the wartime Navy. Fewer than two percent of personnel wore dolphins. Yet by the end of the Pacific War, submarines had strangled more than half of Japan’s merchant shipping. That success did not come cheaply. Fifty-two boats did not return. Thirty-five hundred and six men went on what submariners still call eternal patrol. No other branch of American service lost such a high percentage of its own.

It is easy, with charts and tonnage tables, to turn that arithmetic into abstraction. February resists that temptation. The losses in this month fall across the full arc of the war, from the early improvisation and retreat of 1942 to the grinding efficiency and lethal countermeasures of 1945. USS Shark, Amberjack, Grayback, Trout, and Barbel did not vanish in a single pattern or for a single reason. What binds them together is timing and consequence. Each was lost at a moment when the submarine force was being asked to do more with less margin for error, and each loss marked a change in how the war at sea was being fought.

The men who served in submarines understood this long before historians put it into tidy language. Submarine warfare was never about glory. It was about pressure. Pressure on supply lines, pressure on enemy morale, pressure on the men themselves, who lived in steel tubes that smelled of diesel fuel, sweat, and cooked coffee grounds. They knew that most patrols would be dull, punctuated by moments of terror, and that sometimes those moments would be final.

The first February loss came when the war was still young and nothing about it felt settled. USS Shark SS-174, belonged to a Navy that was running backward as often as it was advancing. Pearl Harbor had blown open the Pacific. The Japanese offensive swept through the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies with a speed that left Allied commanders scrambling to save men, equipment, and time. Submarines were not yet the hunters they would become. They were couriers, scouts, evacuation platforms, and sometimes lifeboats.

Shark had already done work that rarely shows up in victory tallies. In December 1941 she helped evacuate Asiatic Fleet staff from Manila, including Admiral Francis Rockwell, carrying them south to Surabaya ahead of the Japanese advance. This was not a glamorous mission, but it mattered. Command staffs that survive can fight again. On January 6, 1942, Shark narrowly escaped a Japanese torpedo. It was an early reminder that even transit carried mortal risk.

Her final patrol began in that same atmosphere of urgency and uncertainty. Shark departed Surabaya on January 5, assigned to waters near Menado and the Makassar Strait. Communications were sparse and cautious. On February 2 she reported depth charge attacks, a phrase that appears dry on paper but meant hours of silence, men holding their breath, listening to screws overhead and explosions rattling the hull. On February 7 she sent her last radio message, reporting pursuit of a cargo ship. Orders followed directing her toward the Makassar Strait. Shark acknowledged. Then the radio went quiet.

What happened next came from the other side of the fight. On February 11, 1942, the Japanese destroyer Yamakaze encountered a submarine east of Menado. The destroyer opened fire, expending forty-two shells. According to Japanese records, the submarine sank almost immediately. Afterward, voices were heard in the water. No rescue was attempted. It is a small detail, and a brutal one. It also marks a turning point. Shark was the first United States submarine lost to enemy antisubmarine warfare. Not to accident, not to mechanical failure, but to a system that was already learning how to hunt the hunters.

There is a temptation to read inevitability backward into events like this. In February 1942, nothing was inevitable. The Japanese antisubmarine effort was still crude by later standards. Visual sightings, gunfire, and basic hydrophones dominated. Yet Shark was gone all the same, and with her went her entire crew. They were men operating at the edge of doctrine, using boats designed for a different kind of war, doing what was asked because there was no one else available to do it.

This was the price of desperate defense. The Navy learned from Shark’s loss, but it learned slowly, under fire, patrol by patrol. February would claim more boats as those lessons accumulated, and as the submarine force grew sharper teeth while its adversaries learned to look deeper into the sea. Those later losses would come in very different circumstances. For now, in early 1942, the war was still being written in pencil, and USS Shark disappeared into the margins.

By February 1943 the war had changed its shape, though not yet its cost. The frantic withdrawals of the first year were giving way to a hard, grinding effort to seize and hold ground in the Solomons. Guadalcanal had taught the Navy that control of sea lanes could decide campaigns before armies ever met. Submarines were no longer improvising on the margins. They were now expected to interdict supply lines, isolate battlefields, and operate aggressively in waters crawling with enemy escorts.

USS Amberjack SS- 219, embodied that transition. She was a Gato class boat, part of a new generation built for range, endurance, and sustained offensive patrols. Before her final voyage, she had already performed work that blurred the line between combat and logistics. On earlier patrols she ran aviation gasoline and bombs into Guadalcanal, a reminder that submarines were often the only reliable lifeline to forces ashore. The men aboard understood that these missions mattered as much as sinking ships, even if they rarely made headlines.

Her third war patrol was different. Amberjack was hunting. Operating in the Solomon Islands, she targeted Japanese coastal traffic and the fast-moving resupply runs that Allied sailors nicknamed the Tokyo Express. On February 4, 1943, she engaged enemy vessels on the surface. During that action, Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Arthur C. Beeman was killed by machine gun fire. It was a stark example of how close submarine combat could become. These were not distant torpedo shots followed by quiet withdrawal. Sometimes the war came right up to the deck guns.

Amberjack pressed on. Her last transmission came on February 14. She reported sinking a ship and, in an unusual detail, recovering a Japanese aviator taken prisoner. It was a small window into the strange, fleeting human encounters that occurred even in total war. Enemy airmen pulled from the water, interrogated in cramped control rooms, then transferred when opportunity allowed. That message was the last anyone heard from her.

Two days later, Japanese records filled in the silence. A patrol plane sighted a submarine off Cape St. George. An attack followed, coordinated between the aircraft, the torpedo boat Hiyodori, and Subchaser No. 18. Depth charges were dropped, nine in total. Heavy oil and debris rose to the surface. For experienced antisubmarine crews, that was confirmation enough. Amberjack and her crew were gone.

By the time of her loss, the contest beneath the sea had grown sharper on both sides. American submarines were more aggressive, more capable, and more willing to stay in contested waters. Japanese defenses, while still uneven, were improving through practice and grim necessity. The result was not balance, but escalation. Every patrol carried higher expectations and higher risk.

That escalation reached its peak in February 1944, a month that claimed two boats whose careers illustrated just how lethal the submarine campaign had become.

USS Grayback SS-208, was no novice. She ranked among the most successful American submarines of the war, credited with more than sixty-three thousand tons of enemy shipping sunk. Her crew knew how to fight, how to stalk convoys, and how to survive repeated patrols in hostile waters. By her final patrol she was low on torpedoes, the usual sign that it was time to head home. Success carried its own exhaustion.

On February 27, 1944, south of Okinawa, Grayback was spotted on the surface by a Nakajima B5N bomber launched from the carrier Zuikaku. The aircraft attacked, dropping a five-hundred-pound bomb. Follow up depth charges sealed her fate. The sea closed over a boat that had done nearly everything asked of her.

For decades, Grayback’s loss carried an added cruelty. A translation error made in 1946 misplaced her sinking by roughly one hundred miles. Families lived without certainty. Historians worked with flawed charts. It was not until 2019, when the Lost 52 Project located the wreck at a depth of over fourteen hundred feet, that the record was corrected. Steel and silt finally told the truth where paperwork had failed.

Only two days later, February claimed USS Trout SS-202. Trout was already a legend long before her final patrol. In 1942 she had carried twenty tons of gold and silver out of Corregidor, a mission so unusual that it sounded almost apocryphal even at the time. But legend did not confer immunity.

On February 29, 1944, Trout intercepted a Japanese convoy carrying elements of the 29th Division bound for Guam. She attacked decisively, sinking the transport Sakito Maru. Thousands of Japanese troops went down with her. It was one of the deadliest single blows delivered by an American submarine, and it had strategic consequence. A regiment that would never reach the Marianas could not fight there later.

The response was immediate. The destroyer Asashimo counterattacked, dropping nineteen depth charges. Trout did not survive the barrage. The ocean floor became her logbook, her final patrol report written in pressure and silence.

By the end of February 1944, the submarine war had reached a grim maturity. American boats were inflicting catastrophic losses on Japan’s ability to move men and material. Japanese forces, though strained and often outmatched, had learned enough to exact a terrible price in return. Skill no longer guaranteed survival. Experience no longer ensured a margin of safety. Even the best boats, commanded by capable officers, could vanish between radio checks.

The men who followed these losses knew what they meant. They did not retreat from the mission. They adjusted, they learned, and they kept going. February would take one more boat before the war ended, under conditions that showed just how tight the noose around Japan had become.

By February 1945 the Pacific War had narrowed and tightened. Japan’s merchant fleet was in ruins. Fuel was scarce. Crews were poorly trained. Yet the waters nearest the remaining lifelines had become the most dangerous of all. Shallow seas, narrow straits, constant air patrols, and increasingly sophisticated detection tools turned every submerged mile into a calculated risk. Submarines were still winning the war at sea, but they were doing so inside a shrinking box.

USS Barbel SS-316, entered this phase as part of a coordinated effort to seal off what remained of Japanese coastal traffic. She was a Balao class boat, tougher than her predecessors, built to dive deeper and survive punishment that would have crushed earlier designs. In early 1945 she operated as part of a wolfpack with USS Perch and USS Gabilan, covering the Balabac Strait near Palawan. It was exactly the kind of assignment that looked straightforward on a chart and deadly in execution.

Barbel’s patrol reports told a familiar late war story. Constant aircraft contacts. Repeated depth charge attacks. Little rest. Little margin. Early February brought daily pressure, the kind that wore down even experienced crews. The sea was shallow enough that depth became a liability rather than protection. Every maneuver had consequences measured in feet.

On February 4, 1945, Japanese aviators reported attacking a submarine southwest of Palawan. According to their account, a bomb scored a direct hit near the bridge. The submarine plunged under what was described as a cloud of fire and spray. There were no further sightings. Barbel did not answer roll call.

By the standards of earlier years, her loss would have seemed sudden. By the standards of 1945, it was almost expected. Japanese antisubmarine warfare had evolved under pressure. What began with lookouts and hydrophones now included airborne radar and Magnetic Airborne Detectors. Aircraft could search wide areas quickly, then pass contacts to surface escorts. Depth charge patterns had improved. Crews were more practiced. None of this reversed the strategic outcome of the war, but it made the final months brutally efficient at killing submarines.

Looking back across the February losses, patterns emerge without settling into neat explanations. USS Shark fell during a retreat, when the Navy was improvising survival. Amberjack was lost in the transitional phase, when submarines were learning to dominate contested waters and the enemy was learning how to respond. Grayback and Trout disappeared at the height of American effectiveness, when success encouraged boldness and Japanese defenses had sharpened enough to punish it. Barbel was lost in the endgame, when the noose was tight and every patrol pressed into waters that offered no forgiveness.

There were other contributing factors that do not fit cleanly into timelines. Early in the war, torpedo failures haunted submarine commanders. The Mark 14 torpedo ran deep, detonated erratically, and sometimes circled back toward the firing boat. While not directly responsible for the February losses discussed here, these defects shaped behavior, forcing boats to stay exposed longer and take risks that compounded danger. As the war progressed, aggressive tactics became standard. Convoys were larger, escorts heavier, and commanders were expected to engage anyway. The margin for hesitation narrowed along with the war itself.

What ties these losses together is not a single cause but a shared condition. Submarines operated alone. There was no immediate rescue when things went wrong. Depth charges did not wound, they erased. When a boat failed to return, the ocean kept its answers unless chance or technology later intervened.

That is why discoveries like the 2019 identification of Grayback matter. They are not triumphs of exploration for their own sake. They restore accuracy to the record and finality to families who lived for decades with uncertainty. They remind us that history is not finished simply because a war ends.

The strategic impact of these February patrols cannot be separated from their cost. Even as boats were lost, others were sinking troop transports, starving factories, and isolating garrisons that would later fall without meaningful resistance. The submarine force broke Japan’s ability to wage modern war long before bombs fell on cities. That truth exists alongside the fact that the men who achieved it paid a disproportionate share of the price.

The crews of Shark, Amberjack, Grayback, Trout, and Barbel did not set out to become symbols. They were professionals doing their jobs under conditions that rewarded persistence and punished error without mercy. They left behind no last speeches, only routine patrol reports that ended mid-sentence or not at all.

February remembers them not because the month is cruel, but because history is honest. These boats went out when they were needed and did not come back. The Navy marked them as on eternal patrol, a phrase that carries neither sentimentality nor comfort. It is simply a statement of fact.

In the quiet rituals that survive the war, the tolling of the boats, the reading of hull numbers, the pause after each name, February still has a voice. It speaks softly, without argument. It asks only that we remember that victory at sea was not abstract, and that the ocean never forgets its dead.

Leave a comment