On a cold January morning, Monday, the 24th, in 1944, the war arrived quietly in northwest Ohio.

It came folded in newsprint.

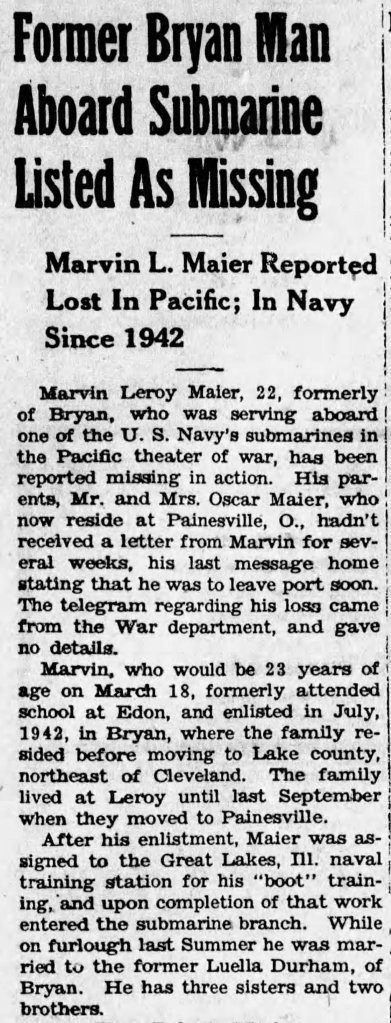

The Bryan Democrat carried a small headline that did not shout and did not explain much: Former Bryan Man Aboard Submarine Listed As Missing. Beneath it was the name Marvin Leroy Maier, twenty two years old, a son, a husband, a sailor. He had last written home to say he would be leaving port soon. Now his parents had received a telegram from the War Department. No details. Just the word missing.

The article did what hometown papers always did during the war. It sketched a life in a few careful lines. Born in Bryan. Schooled in Edon. Enlisted in July 1942. Trained at Great Lakes. Assigned to submarines. Married on furlough the previous summer. Three sisters. Two brothers. The kind of inventory that reads like a census and feels like a prayer.

What the paper could not say, and what the Navy itself did not yet know how to say, was that Marvin Maier was already dead. He had been dead for more than two months, somewhere in the western Pacific, aboard a submarine that never made a second patrol.

To understand that notice in the Bryan Democrat, you have to go backward. Far backward. Across the ocean. Into the dark.

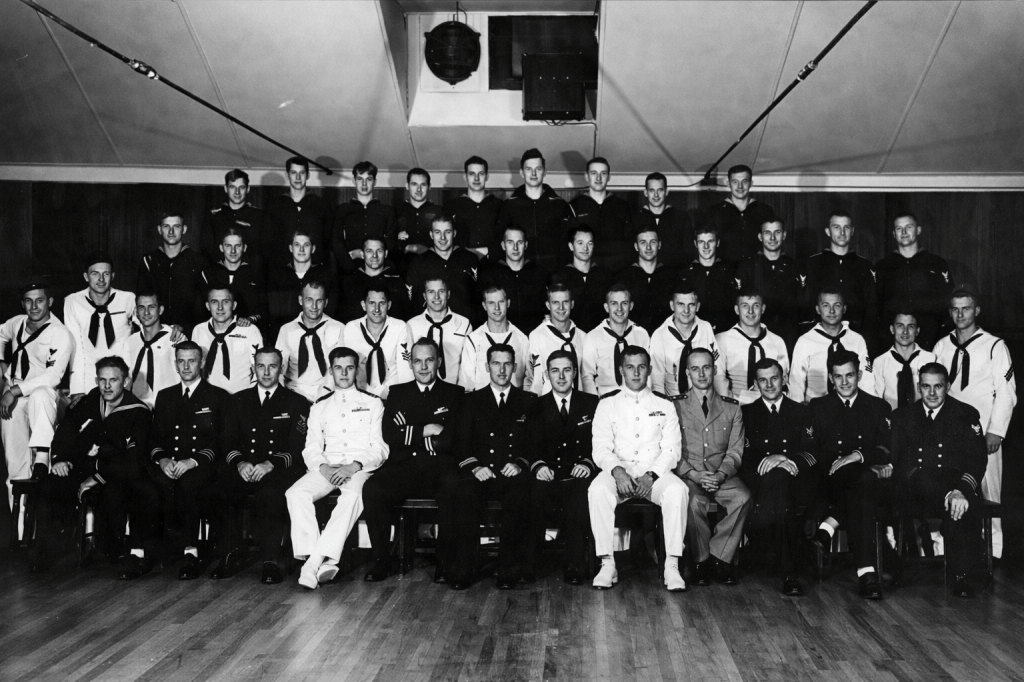

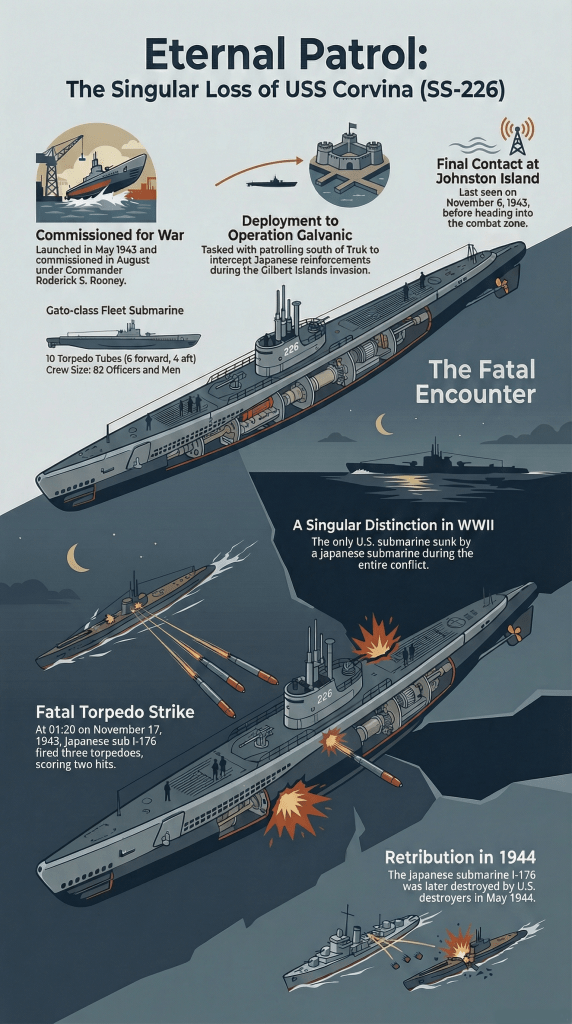

In November 1943, Corvina was brand new to war. A Gato class fleet submarine built in Groton, commissioned that August, and sent west with a crew that had trained hard but had not yet been tested together under fire. Her skipper, Commander Roderick S. Rooney, took her out of Pearl Harbor on November 4 for her first war patrol.

The assignment was deadly serious. Corvina was ordered to patrol south of Truk Lagoon, the Japanese Navy’s central Pacific stronghold, during the opening phase of Operation Galvanic, the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. Submarines like Corvina were sent out as pickets, meant to intercept enemy ships before they could threaten the invasion force. It was a job that demanded patience, silence, and luck.

She refueled at Johnston Island on November 6 and headed west. That was the last time anyone heard from her.

Unknown to her crew, American intelligence had already warned that a Japanese submarine was operating in the same waters. Messages intercepted through ULTRA identified the enemy boat. The warning went out. It did not change the geometry of the sea.

Back in the Allied command structure, silence lingered before it hardened into certainty. Corvina failed to acknowledge orders. She did not arrive for a scheduled rendezvous. At first, commanders hoped for radio failure or operational disruption. The Pacific had taught them to hope carefully.

On the night of November 16, the Japanese submarine I-176 sighted an American submarine running on the surface. The identification was wrong, but the target was real. The American boat was almost certainly Corvina, charging her batteries in the darkness, doing what submarines had to do to survive.

Shortly after midnight on November 17, I-176 submerged, maneuvered, and fired three torpedoes.

About twenty five seconds later, two heavy explosions shook the Japanese submarine. When the crew returned to the surface, they found debris and a thick oil slick spreading across the water. No counterattack came. No gunfire. No radio transmission. The American submarine was gone.

On December 23, 1943, the Navy officially listed Corvina as presumed lost. The public announcement came in March 1944. By then, newspapers like the Bryan Democrat had already begun printing the human consequences, one name at a time.

Marvin Maier’s parents were told nothing more than the paper could print. No coordinates. No account of battle. Just the knowledge that their son had gone to sea in a steel hull and never come back.

History would later confirm what no one in Bryan could have known that January morning. Corvina was the only American submarine sunk by an enemy submarine during the entire Second World War. A singular loss in a campaign otherwise defined by American undersea dominance.

There is one more cruel detail. Japanese records suggest that during the encounter, Corvina may have fired a torpedo that struck I-176 but failed to detonate. A hit that did nothing. A malfunction measured not in machinery, but in lives.

War does not honor intention. It honors results.

The wreck of Corvina has never been found. She remains somewhere south of Truk, her hull settled into silence, her crew still together. Their names are carved on the Courts of the Missing in Honolulu. Models and plaques stand in places far from the sea. In Ohio, a newspaper clipping survives, yellowed and careful, still doing its quiet work.

The loss of Corvina is often remembered for its statistical uniqueness. One submarine. One enemy submarine. A rare thing.

But the truth begins where the statistics end.

It begins with a telegram, a folded newspaper, and a young man from Bryan who left port soon and never came home.

Leave a comment