The USS Alexander Hamilton entered the Cold War quietly, which was the only acceptable way to enter it. When her keel was laid at Electric Boat in Groton in June 1961, the United States was still learning how to live with nuclear weapons without letting them consume every waking thought. Strategy had moved beyond bombers and bravado. What mattered now was endurance. The Hamilton was conceived as a patient thing, meant to vanish beneath the surface and stay vanished, carrying consequences that no adversary could afford to ignore. She would become one of the Forty One for Freedom, a fleet built not to fight wars, but to prevent them by making certainty impossible.

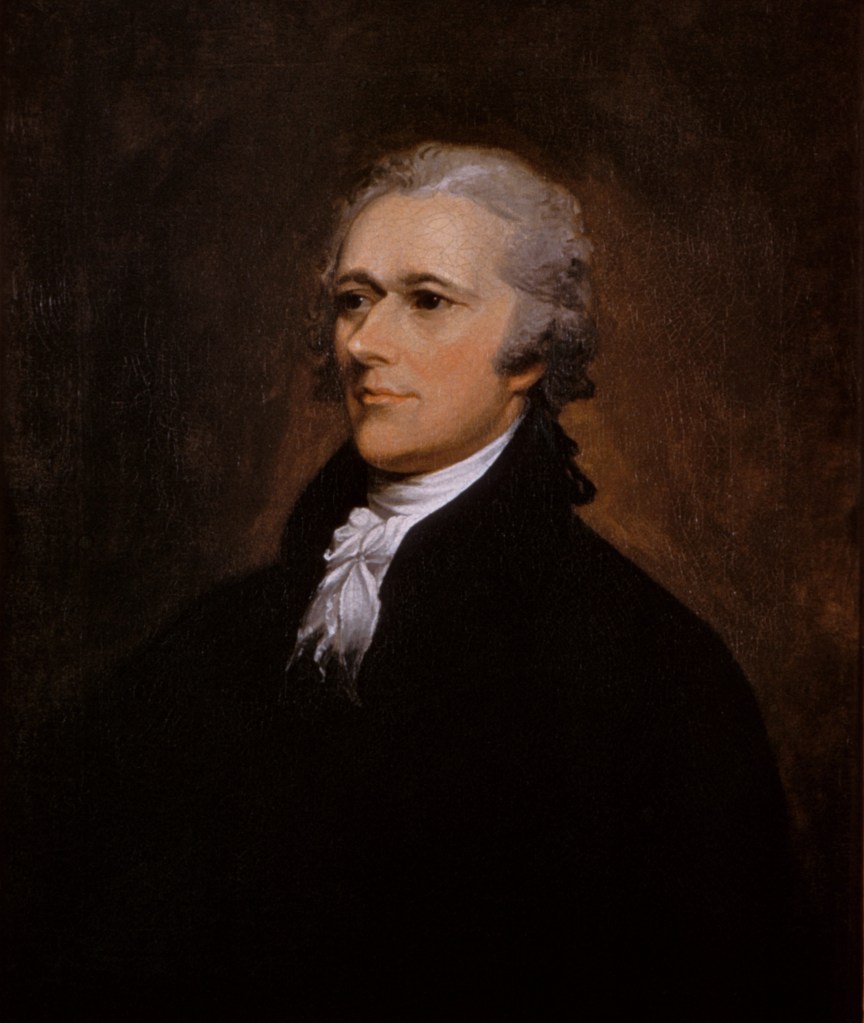

Alexander Hamilton, the man whose name the submarine carried into the depths, would have understood the logic of deterrence even if the technology would have startled him. Born on January 11, 1755 (or possibly 1757), in the West Indies, Hamilton grew up with uncertainty baked into his story, including the year of his own birth. That ambiguity followed him into a life defined by precision of thought and impatience with disorder. He arrived in North America as a young immigrant and rose quickly, not by charm, but by force of intellect and relentless energy. As George Washington’s aide, and later as the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton argued that a republic survived only if it built durable institutions and prepared for dangers before they arrived. He pushed for a standing navy because he believed national weakness invited catastrophe. Hamilton distrusted wishful thinking, favored structure over sentiment, and accepted that power required responsibility. Those instincts made him an unusually fitting namesake for a submarine designed to preserve peace by being ready for war, unseen, disciplined, and built to endure.

There was symbolism in her name that went beyond patriotic habit. Alexander Hamilton, the man, distrusted disorder and believed institutions mattered more than personalities. He helped build a Navy because he understood that a young republic survived by preparing for threats it hoped never to face. The submarine that bore his name carried that same sensibility. It was sponsored by a direct descendant of Hamilton himself, Mrs. Valentine Hollingsworth Jr., a reminder that the Cold War was not some abstract chess match but a continuation of choices made long before missiles replaced masts.

The Alexander Hamilton was a Lafayette class ballistic missile submarine, built large and sturdy for her time. She measured 425 feet long, displaced more than 8,000 tons submerged, and was powered by an S5W nuclear reactor that would define a generation of American submarines. She was commissioned on June 27, 1963, with two crews from the start, Blue and Gold, an acknowledgment that deterrence did not rest on steel alone. It rested on people who had to remain sharp while the rest of the world slept. Norman Bessac commanded the Blue Crew, Benjamin Sherman the Gold, and between them they set the tone for a boat that would spend decades rotating through silence and responsibility.

Her early years followed a rhythm that became familiar across the ballistic missile force. Shakedown cruises in 1963 ironed out the inevitable problems, mechanical and human alike. By March 1964 she was forward deployed to Rota, Spain, joining Submarine Squadron 16. Rota was not glamorous, but it was strategic. From there, Hamilton could slip into the Atlantic quickly, patrol, return, and repeat the cycle without ceremony. In January 1965 she shifted north to Holy Loch, Scotland, under Submarine Squadron 14. Holy Loch was a strange outpost, a quiet anchorage that briefly became one of the most consequential places on earth. From there, the Hamilton patrolled the North Atlantic and Norwegian Sea, maintaining a presence no one could see but everyone had to assume was there.

Life aboard her was defined less by excitement than by routine. Deterrent patrols were long, monotonous, and psychologically demanding. Sailors measured time by watch rotations and maintenance cycles, not by dates. The boat itself became the world. The Hamilton operated under SUBSAFE discipline, a system forged after tragedy, and no one aboard forgot why those rules existed. The loss of Thresher was still close enough to feel personal. Every valve, every weld, every checklist was a small act of respect for lessons learned the hard way.

In 1967 the Hamilton returned to Groton for her first major overhaul and nuclear refueling. This was more than maintenance. It was evolution. She emerged upgraded from Polaris A 2 to Polaris A 3 missiles, extending her reach and reinforcing her relevance. By late 1968 she was back at Rota, resuming patrols as if the interruption had never happened. That was the nature of the job. The world above might change headlines weekly, but the mission below remained stubbornly the same.

The most dramatic transformation of the Alexander Hamilton came in the 1970s. In January 1973 she entered Newport News Shipbuilding for a second refueling and conversion to carry Poseidon C 3 missiles. This was not a cosmetic change. Poseidon brought MIRV capability, allowing a single missile to carry multiple independently targetable warheads. It altered the arithmetic of deterrence in ways that were both reassuring and unsettling. The Hamilton emerged more lethal, but also more tightly bound to the logic of restraint. When one platform can do that much damage, restraint becomes a survival skill, not a moral aspiration.

After her Poseidon conversion, the Hamilton proved she was more than a missile truck. She conducted Arctic operations in 1975 and 1976, earning her Blue Nose and testing sonar performance in ice choked waters. These were demanding evolutions, technically and psychologically. Surfacing through ice, operating where charts were thin and conditions unforgiving, forced crews to trust their training absolutely. It also demonstrated to any observer paying attention that American submarines could operate where they were least expected.

Not every incident was so controlled. At some point in the late 1970s or early 1980s, accounts differ, the Hamilton snagged the fishing nets of the Scottish trawler Aquila in the Sound of Jura. The submarine towed the unfortunate vessel backward for nearly two miles before the nets were cut free. It was a moment of unintended comedy, the kind sailors remember fondly years later, but it also illustrated how even the most secret machines still intersected with ordinary lives. The Cold War was never entirely abstract to the people caught along its edges.

By the mid 1980s, the Alexander Hamilton was supposed to be finished. Arms control treaties, particularly SALT II, imposed limits that forced the Navy to make hard decisions. New Ohio class submarines were entering service, larger and more capable, and older boats were scheduled to go. The Hamilton was slated for decommissioning in 1986, her long vigil at an end. Then chance intervened. The USS Nathanael Greene ran aground and suffered damage severe enough to remove her from service. Fleet numbers still mattered. The Hamilton was granted a reprieve, not out of sentiment, but necessity.

That reprieve required work. The Hamilton underwent a short maintenance availability, then transited the Panama Canal to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for refueling. She emerged in 1989 with new life, homeported at Bangor, Washington. Her role changed subtly but significantly. No longer a frontline deterrent in the Atlantic, she became a Pacific asset, serving as what sailors wryly called a Trident Buster. She acted as an aggressor submarine, training crews of the newer Ohio class boats by challenging them with the tactics and habits of an older generation. There was quiet satisfaction in that role. Experience has a way of humbling novelty.

In September 1989, the Alexander Hamilton conducted the final launch of a Poseidon C 3 missile. It was an unremarkable event on paper, but historically weighty. It marked the end of an era, the last operational firing of a system that had carried much of the Cold War on its shoulders. The Hamilton continued on, not as a symbol, but as a working ship, accumulating dives and miles with little fanfare.

She celebrated her silver anniversary in June 1988, a milestone few submarines reached in active service. In April 1992, she completed her 1,000th dive, setting a record for American ballistic missile submarines at the time. These numbers mattered not as bragging points, but as evidence of durability, both mechanical and human. The Lafayette class had been designed for a specific moment, yet here was the Hamilton, still relevant decades later.

Her end came with a symmetry that sailors appreciate. On August 18, 1992, exactly thirty years after her launch, the Alexander Hamilton was deactivated. She was officially decommissioned and stricken from the Navy list on February 23, 1993. Recycling followed quickly. By February 28, 1994, the steel that had once carried global consequences had been dismantled and repurposed. That was as it should be. Submarines are tools, not monuments.

What remains is less tangible. Former crew members remember port calls in Dunoon and Plymouth, Blue Nose initiations, the quiet rivalry between Blue and Gold crews, and the peculiar pride that came from doing something important without being seen. A memorial bench at Patriots Point offers a place to sit and remember, but the real legacy lives in the habits and expectations carried forward by those who served aboard her.

The USS Alexander Hamilton mattered because she lasted. She bridged technological eras, survived strategic reshuffling, and adapted when circumstances demanded it. She embodied a truth that the Cold War taught painfully well. Strength is not always loud. Sometimes it is patient, persistent, and willing to be forgotten so that others can sleep.

Leave a comment