January does not announce itself gently in naval history. It arrives cold, dark, and already carrying the weight of decisions made months or years earlier. For the United States submarine force, January became a recurring point of reckoning, a month when machinery, weather, navigation, and war itself seemed to conspire against boats already stretched thin. The losses that occurred during January across multiple years of the Second World War were not part of a single battle or campaign. They were scattered in geography and cause, but unified by circumstance. They tell a story not of failure, but of exposure, of a service operating at the edge of what men and steel could endure.

The early months of 1942 were particularly unforgiving. American submarines were being pushed into service before doctrine had fully caught up with reality, and before crews had the benefit of hard earned experience. The S class boats bore the brunt of that transition. Designed during the First World War and modernized unevenly in the years that followed, they were never meant to fight a global war in tropical waters against a modern enemy. Yet that was precisely what they were ordered to do.

USS S-36 was one such boat. By January 1942, she was already worn, her systems temperamental, her margin for error thin. Operating in the Netherlands East Indies, she was tasked with patrols through narrow, poorly charted waters under blackout conditions. On the morning of January 20, before sunrise, she ran hard aground on Taka Bakang Reef. There was no enemy nearby, no gunfire, no depth charges. The reef itself did the damage, tearing open compartments and flooding the forward battery spaces. What followed was a quiet but deadly danger that every submariner understood too well. Seawater mixed with battery acid, producing chlorine gas that crept through the boat. The crew was forced to abandon the interior and escape topside.

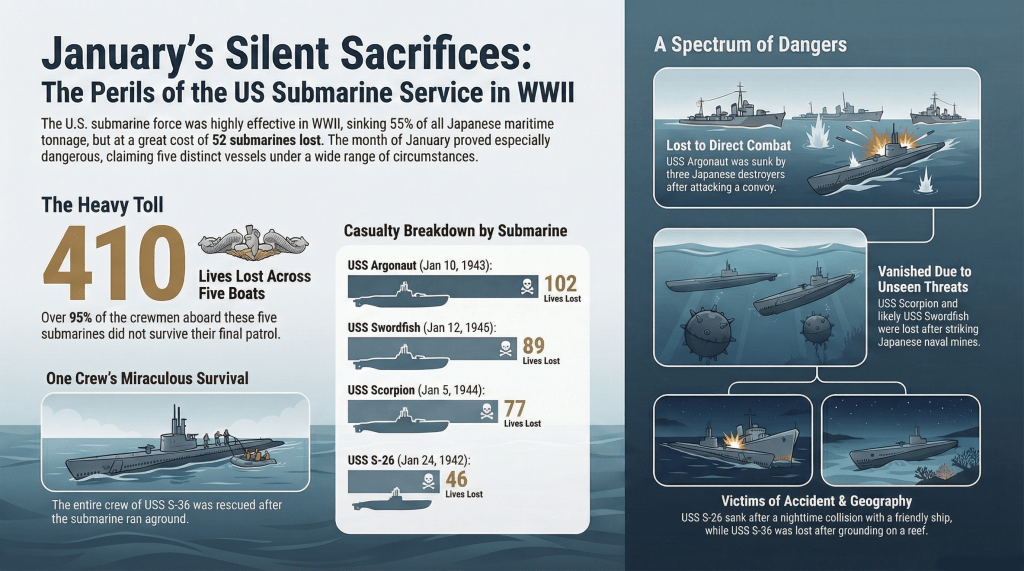

What makes the loss of S-36 unusual in the January record is that every man survived. Dutch vessels rescued the crew the following day, and the commanding officer scuttled the submarine to prevent capture. The Navy recorded the loss, assigned blame where it could, and moved on. Yet the incident exposed something important. Even without an enemy present, submarine warfare was inherently lethal. Navigation errors, mechanical fatigue, and environmental hazards could be just as final as a destroyer attack. January did not need an adversary to claim a boat.

Four days later, the war claimed another S class submarine, this time in waters that should have been safe. USS S-26 was operating in the Gulf of Panama, an area considered defensive rather than contested. The submarine was running on the surface at night, darkened ship, escorted by American patrol vessels. Orders were passed by signal. Not all were received. In the confusion, the submarine chaser PC-460 altered course directly into S-26. The collision was catastrophic. The submarine was struck amidships and sank in less than a minute.

Three men on the bridge were thrown clear by the impact and survived. Forty six others went down with the boat. There was no opportunity for escape, no time for corrective action. It was a loss caused entirely by miscommunication and the hazards of night operations under wartime conditions. No enemy ever knew it happened. No Japanese record would reflect the sinking. Yet for the families of those forty six men, the war became real in an instant.

The loss of S-26 also revealed a truth that would recur throughout the submarine war. Danger did not always come from the other side. Friendly forces, operating under pressure, could be just as deadly. Training, coordination, and experience would improve as the war went on, but January 1942 showed how unforgiving the learning curve could be. The submarine force was being blooded not only by the enemy, but by its own growing pains.

These early January losses carried another weight. They happened at a time when American submarines were not yet achieving significant success. The torpedo crisis had not been solved. Commanders were still adjusting to aggressive patrol patterns. Crews were still learning how to fight a war that bore little resemblance to peacetime exercises. Losses like S-36 and S-26 did not come with offsetting victories. They were costs paid in advance, with interest accruing slowly.

When people later spoke of the Silent Service as elite or decisive, they often skipped over these months. Yet January 1942 formed part of the foundation on which later success rested. The lessons were harsh and poorly timed, but they were absorbed. Navigation practices improved. Escort coordination tightened. Training emphasized the dangers of night operations. These changes were not abstract. They were paid for by boats that never returned.

By January 1943, the submarine force was changing in both capability and confidence. Fleet boats were entering service in greater numbers, patrol doctrine was evolving, and commanders were beginning to press attacks with more coordination and aggression. Yet January remained indifferent to progress. The month did not discriminate between old boats and new ones, between experimental designs and proven platforms. On January 10, 1943, it claimed one of the most unusual submarines ever built by the United States Navy.

USS Argonaut began her life as V-4, a massive minelaying submarine conceived during a period when naval planners believed that size and endurance would offset vulnerability. She was the largest non nuclear submarine the Navy ever operated, displacing more than four thousand tons submerged. By the time the war began, her original mission had already been overtaken by events. Mine warfare proved impractical, and Argonaut was converted into a transport submarine. In that role, she carried Marine Raiders for the diversionary raid on Makin Island in August 1942, a mission that placed her briefly in the spotlight.

By early 1943, Argonaut was assigned to patrol waters near New Britain and Bougainville. These were heavily contested seas, crowded with Japanese shipping and aggressively patrolled by destroyers. On January 10, she encountered a Japanese convoy escorted by three destroyers. She attacked. What followed was witnessed in part by an American Army aircrew overhead, a rare circumstance that provided external confirmation of events that submarines usually recorded only in silence.

Argonaut was counterattacked almost immediately. Depth charges damaged her, forcing her bow to break the surface at a steep angle. Once exposed, she became vulnerable in a way submarines are never meant to be. Japanese destroyers closed and shelled her until she slipped beneath the water. All one hundred and two men aboard were lost. It remains the single greatest loss of life suffered by the American submarine force in combat.

There is a temptation to frame Argonaut final moments as heroic or tragic in equal measure. Those words, while not wrong, do not fully explain what happened. Argonaut was large, slow to dive, and operating in waters where destroyers could concentrate quickly. Her design made her vulnerable, and the tactical situation offered little margin for escape. Courage did not alter those facts. The men aboard did what they were trained to do. The outcome was determined by physics, timing, and enemy reaction.

The loss of Argonaut reverberated through the submarine force. It underscored the danger of operating in heavily defended waters without adequate intelligence or support. It also marked the end of the Navy experiments with oversized submarines. The future belonged to smaller, more agile boats that could strike and disappear. January had delivered another lesson, written in blood.

The following year, January 1944, the war had shifted again. American submarines were sinking Japanese shipping at an accelerating pace. The torpedo problems were largely resolved. Crews were experienced, confident, and aggressive. Yet even at the height of effectiveness, submarines remained vulnerable to hazards that could not be fought.

USS Scorpion was a Gato class fleet boat with a strong combat record. She had completed three successful war patrols and had sunk ten enemy ships. On January 3, 1944, she departed Midway for her fourth patrol, bound for the Yellow Sea. Two days later, she attempted to rendezvous with USS Herring to transfer an injured sailor. Heavy seas prevented the transfer. The two submarines separated. Scorpion was never heard from again.

No distress signal was received. No confirmed attack was recorded. When Scorpion failed to return, she was eventually declared lost. Postwar analysis of Japanese records showed no anti submarine actions in her patrol area during the relevant period. The most likely explanation is that she struck a mine. Japanese defensive mining had intensified, particularly at the entrances to the Yellow Sea. Mines were cheap, effective, and indiscriminate. They did not distinguish between experienced crews and inexperienced ones.

Seventy seven men vanished with Scorpion. There were no survivors, no witnesses, no wreckage recovered. For families, the absence of answers became part of the loss. January once again demonstrated that not all casualties come with a narrative. Some simply disappear, leaving historians to reconstruct probabilities rather than events.

By January 1945, the submarine war had entered its final phase. American boats were operating almost with impunity, Japanese shipping was in collapse, and preparations were underway for the invasion of Okinawa. Yet the demand for intelligence had never been greater. Submarines were increasingly tasked with missions that involved observation rather than attack, gathering information that would shape amphibious operations and air campaigns.

USS Swordfish was a veteran of this war. Commissioned before Pearl Harbor, she had the distinction of being the first American submarine to sink a Japanese ship. By the time she departed on her thirteenth patrol, she was an experienced boat with a seasoned crew. Her mission in January 1945 was photographic reconnaissance of Okinawa, a task that carried immense strategic importance. Accurate intelligence would save lives later, though the men gathering it would never know how.

Swordfish acknowledged orders on January 3. After that, her fate becomes uncertain. One American submarine reported a radar contact believed to be Swordfish days later, followed by distant depth charges. Japanese records suggest a merchant ship was sunk in the area, followed by a counterattack that produced oil slicks. Mines were dense around Okinawa, laid in anticipation of invasion. Any of these could have ended her patrol. All eighty nine men aboard were lost.

Swordfish disappearance illustrates the final irony of January losses. By this stage of the war, submarines were winning. Their strategic impact was undeniable. Yet individual boats could still vanish without explanation, claimed by the same hazards that had stalked the force since the beginning. Victory did not make submarines invulnerable. It only increased the number of missions deemed worth the risk.

When viewed together, the January submarine losses do not form a tidy narrative. They involve reefs, collisions, destroyers, mines, and silence. Some crews survived. Most did not. The boats lost ranged from obsolete S class submarines to front line fleet boats. The causes were sometimes clear, sometimes speculative. What unites them is not heroism or error alone, but exposure. Submarine warfare strips away illusion. It leaves men alone with machinery, water, and chance.

These losses matter today not because they offer simple lessons, but because they remind us that success is rarely clean. The submarine force achieved extraordinary results in the Second World War, but those results were built atop months like January, when progress stalled and lives were lost without ceremony. Remembering these boats does not require embellishment. It requires attention, patience, and a willingness to accept that history often refuses to resolve itself neatly.

The men who went down in January did not know they would be part of a pattern. They were simply doing their jobs, in the dark, in the cold, trusting that their training and their ship would carry them through. Sometimes it did. Sometimes it did not. That is the uncomfortable truth at the heart of the Silent Service, and January tells it without apology.

Leave a comment