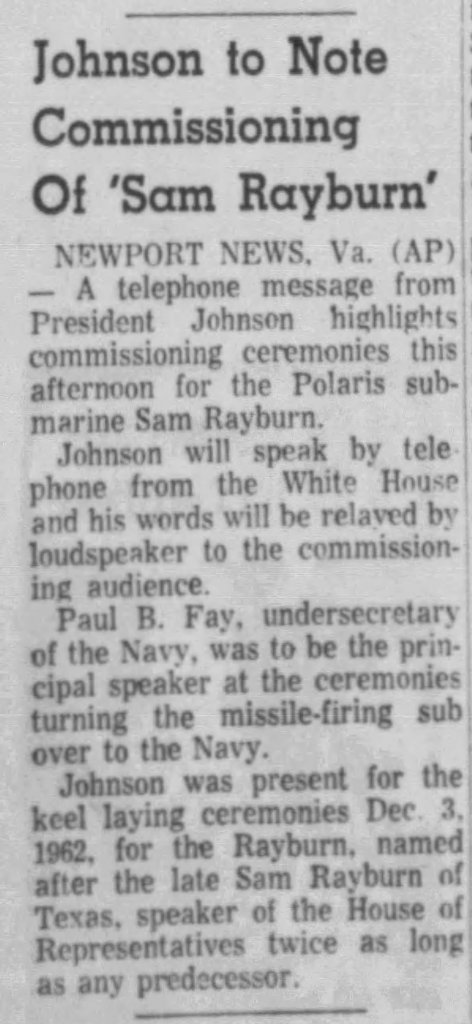

The USS Samuel Rayburn SSBN-635 entered the world quietly, as most serious things do, laid down in December 1962 while the Cuban Missile Crisis was still a fresh bruise on the national psyche. The men who authorized her construction did not need speeches or slogans to understand what they were building. They were responding to a moment when the margin for error had narrowed to the width of a human heartbeat. Submarines like Rayburn were conceived as insurance policies written in steel and uranium, meant never to be cashed, only to exist. She was commissioned on December 2, 1964 at Newport News, carrying the name of a Texas congressman who believed deeply in institutional endurance and disliked theatrical gestures. It was an oddly fitting namesake for a boat designed to remain unseen, unheard, and uncelebrated while doing the most consequential job imaginable.

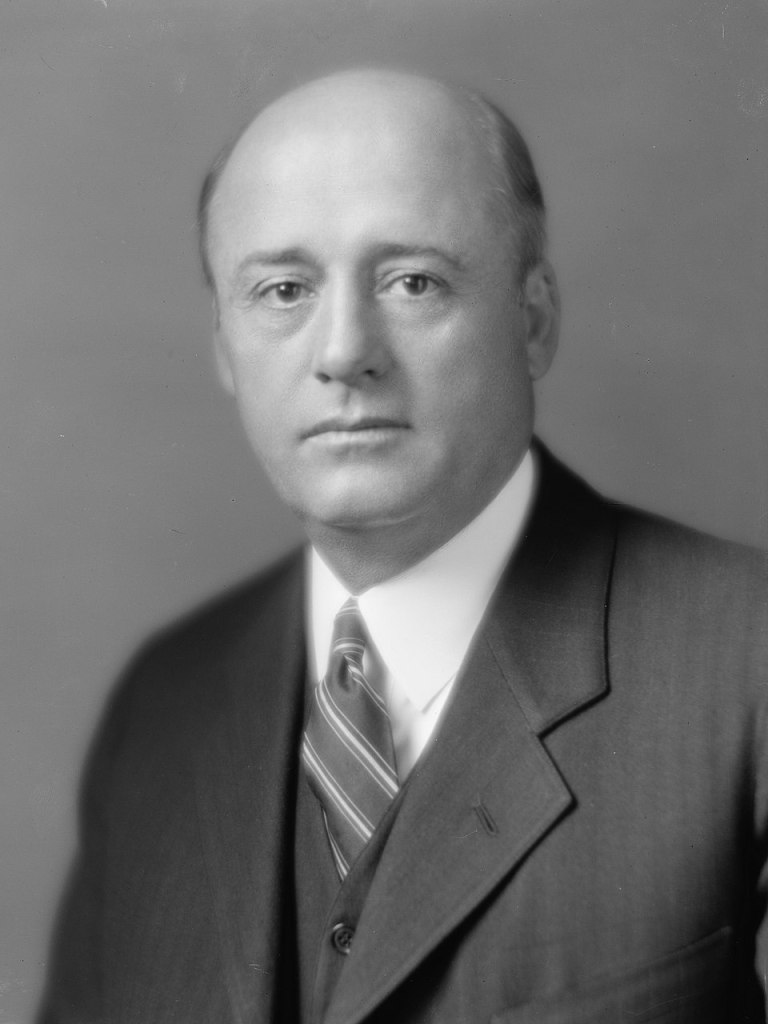

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn himself deserves a pause in the hallway, if only to remind us why a ballistic missile submarine bore his name in the first place. Born on January 6, 1882, in rural Tennessee and raised in North Texas, Rayburn was not a man drawn to spectacle or rhetorical fireworks. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives for more than four decades and spent seventeen of those years as Speaker, longer than anyone before or since. His power came from patience, institutional memory, and a deep belief that government functioned best when it worked quietly and predictably. Rayburn distrusted ideological crusades, disliked grandstanding, and believed compromise was not a weakness but a necessity. He once remarked that any jackass could kick down a barn, but it took a good carpenter to build one. That sensibility, steady, durable, and unsentimental, made him an unusually apt namesake for a submarine whose success depended on remaining unseen, doing its job without applause, and sustaining the republic through endurance rather than drama.

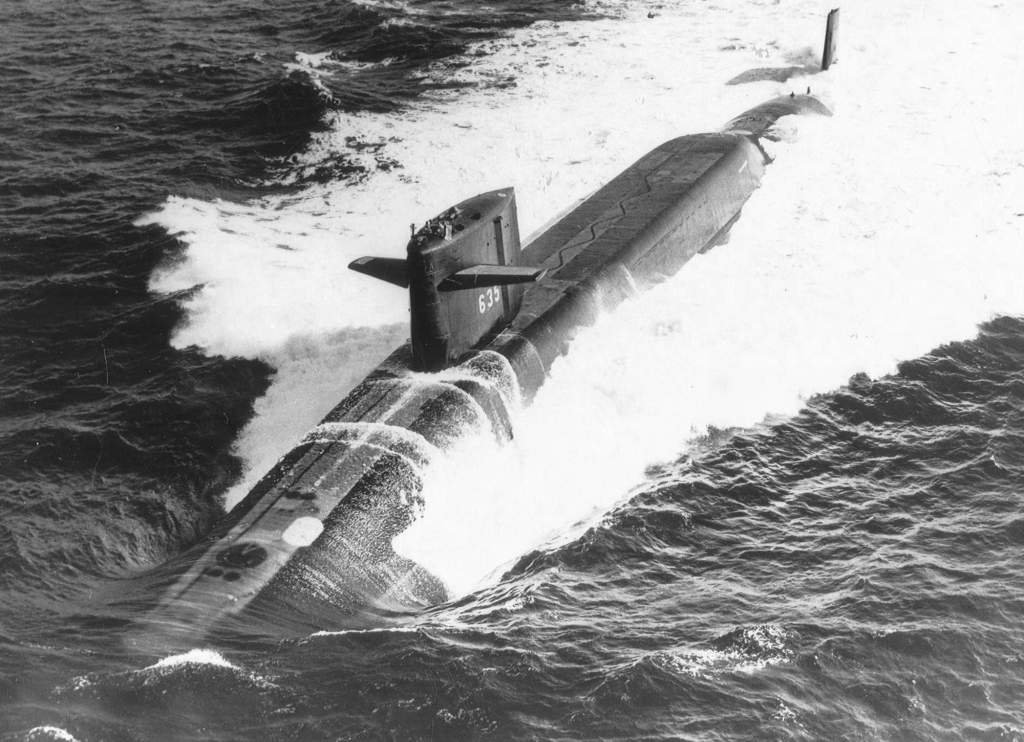

Rayburn belonged to the James Madison class, part of the larger group known as the Forty One for Freedom. The phrase sounds tidy now, almost commemorative, but at the time it was an urgent industrial scramble. The United States was racing to establish a survivable nuclear deterrent, something that could not be wiped out in a first strike, something that could vanish into the ocean and remain there, patient and lethal. Rayburn carried sixteen Polaris A 3 missiles, each one capable of reaching across continents. Her reactor was the Westinghouse S5W, a design that would become the backbone of American nuclear propulsion. She was also built under the shadow of loss. The sinking of USS Thresher in 1963 loomed over every weld and inspection, and Rayburn emerged from the yard wrapped in the newly hardened discipline of SUBSAFE. This was not innovation for innovation’s sake. It was a recognition that complexity without rigor gets people killed.

Her early patrols took her to the Atlantic, operating from Rota, Spain, and later Holy Loch, Scotland. These places appear as dots on a map, but for the crews they were edges of the world, liminal spaces where Cold War abstraction met daily routine. Deterrent patrols were long, monotonous, and unforgiving. Days blurred together under artificial light. The ocean pressed in from all sides. Sailors learned the peculiar intimacy of submarine life, where every sound mattered and privacy was a memory. The Rayburn was not a warrior in the cinematic sense. She was a sentry, pacing slowly in the dark, making sure nothing happened.

Technology refused to stand still, even when strategy tried to freeze the world in place. By the end of the 1960s, Polaris was already giving way to Poseidon. Between 1969 and 1971, Rayburn underwent conversion to carry Poseidon C 3 missiles, larger, more capable, and designed to complicate Soviet defenses. This was not an upgrade driven by vanity. It was driven by arithmetic. Deterrence lives and dies on credibility, and credibility erodes quickly in a technological arms race. After her conversion, Rayburn continued patrols from Holy Loch with Submarine Squadron 14, operating as part of a system that depended on silence, redundancy, and trust in people whose names would never appear in headlines .

There were moments when Rayburn pushed boundaries rather than merely holding the line. She participated in Arctic operations and became the first ballistic missile submarine to surface through the ice during specific tactical tests. This was not bravado. It was proof of concept. The Arctic was both a hiding place and a potential battlefield, and submarines had to prove they could operate there reliably. Surfacing through ice was dangerous, technically demanding, and deeply unsettling for the men involved. It was also necessary. The Cold War rewarded preparation more than courage.

By the early 1980s, the world began to shift in ways that strategy documents had long predicted and planners had quietly dreaded. Arms control treaties moved from aspiration to implementation. SALT II imposed limits that forced hard choices. The Navy could not keep every ballistic missile submarine in service and still field the larger, more capable Ohio class boats coming online. Something had to give. On September 16, 1985, the USS Sam Rayburn was deactivated, not because she was obsolete in any mechanical sense, but because geopolitics demanded accounting. Her missile tubes were filled with concrete. The hatches were removed. The transformation was intentionally irreversible, designed to satisfy treaty verification requirements and signal compliance without ambiguity. This was deterrence by paperwork, and it mattered just as much as deterrence by patrol.

Most ships would have ended their stories there, quietly dismantled and recycled, their steel returning to the industrial bloodstream. Rayburn did not. Instead, she was selected for a second life, one that would ultimately outlast her first. In a radical conversion, her missile compartment was physically cut out of the hull. The remaining bow and stern sections were welded together, shortening the vessel and altering her silhouette in a way that would have been unthinkable during her patrol years. On July 31, 1989, she was reclassified as Moored Training Ship 635. It was a surgical act, both brutal and precise, and it gave Rayburn a new purpose that was arguably more influential than her time at sea .

For more than three decades, Rayburn sat moored at the Naval Nuclear Power Training Unit in Goose Creek, South Carolina. She did not roam oceans or disappear beneath ice. Instead, she became a living classroom. Thousands of officers and enlisted sailors learned nuclear propulsion aboard her decks, standing watch on a fully operational S5W reactor plant. The work was hands on, repetitive, and exacting. Mistakes were corrected immediately. Systems were understood not in theory but in practice. Alongside the former USS Daniel Webster, Rayburn became one of the last working examples of a generation of propulsion technology that shaped the modern Navy. While newer submarines moved toward digital systems and photonics masts, Rayburn taught fundamentals. She taught how things fail. She taught how discipline is maintained when novelty wears off.

There is something quietly poetic about a weapon of mass destruction spending its final decades educating young sailors. Rayburn never launched a missile in anger. Instead, she launched careers. She carried the institutional memory of the Cold War into a Navy that increasingly treated that era as history rather than lived experience. Veterans who trained aboard her often speak of the ship with a mix of affection and respect. She was unforgiving. She was old. She demanded attention. She rewarded competence.

In April 2021, Rayburn was towed from Charleston to Norfolk Naval Shipyard, beginning the final chapter of her long service. This marked the Navy’s first inactivation of a moored training ship, a small bureaucratic milestone that nevertheless signaled a generational handoff. Newer training platforms based on Los Angeles class attack submarines would take over. Rayburn’s reactor was defueled, a process completed in November 2024. Years of sitting in warm water had taken their toll. More than 250 lap plates were welded onto the non pressure hull to address corrosion, not to restore beauty, but to ensure she could survive one last journey. She is scheduled to be towed to Puget Sound for recycling, closing a loop that began more than sixty years earlier .

The USS Sam Rayburn mattered because she embodied continuity in an age obsessed with disruption. She bridged the height of mutually assured destruction and the quieter work of sustaining a professional force. She demonstrated that compliance can be as consequential as confrontation, and that transformation does not always mean erasure. In a Navy that prizes speed and innovation, Rayburn stands as a reminder that endurance has its own kind of power. She did her most important work without drama, without applause, and mostly without being seen. That, in the end, is exactly what she was built to do.

Leave a comment