The USS George C. Marshall was never built to be admired. She was built to be trusted. Like her namesake, she existed for moments when patience mattered more than drama and restraint mattered more than applause. In the Cold War Navy, that was not a slogan. It was a job description.

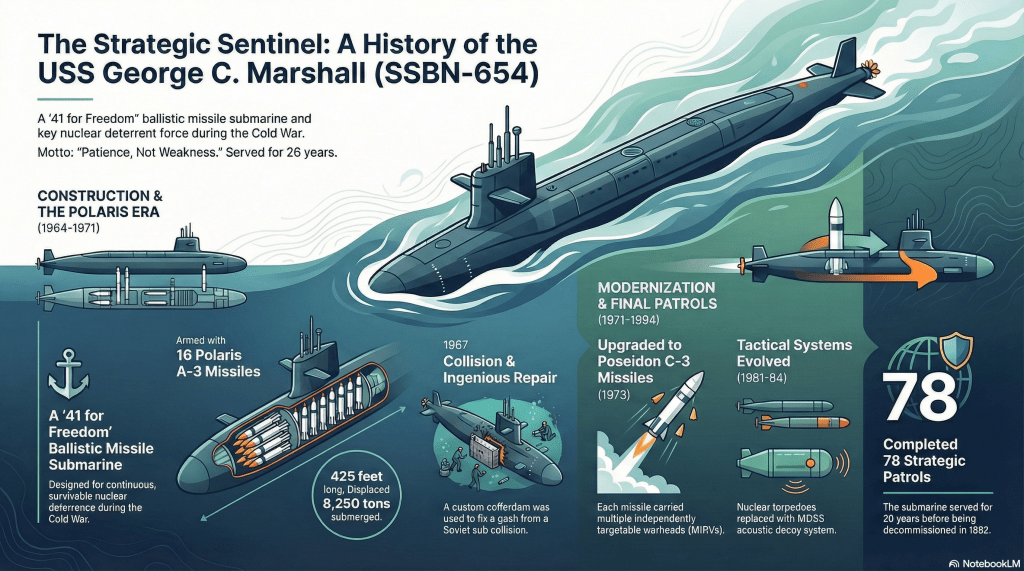

Commissioned in 1966, the USS George C. Marshall (SSBN-654) was a Benjamin Franklin class fleet ballistic missile submarine and part of the Navy’s most consequential experiment in quiet power, the forty one boats collectively known as the “41 for Freedom.” Their mission was brutally simple. Stay hidden. Stay ready. Make sure no rational enemy ever believed a first strike could succeed.

Marshall was designed as a boomer in the purest sense. She was not meant to fight her way through a war. She was meant to prevent one. Her two crew system, Blue and Gold, maximized time on station and minimized the chance that human fatigue would undermine strategic certainty. Deterrence was not glamorous work, but it was relentless.

Her design reflected lessons learned the hard way. At 425 feet long with a beam of 33 feet, she carried the mass and volume required for endurance, not speed records. A single S5W pressurized water nuclear reactor drove steam turbines on one shaft, providing sustained submerged operation measured in months rather than miles. She carried sixteen vertical missile tubes, first for Polaris A 3 missiles and later Poseidon C 3, along with four forward torpedo tubes for self defense. Everything about her favored survivability, redundancy, and quiet competence.

The name mattered. George C. Marshall was the organizer of Allied victory in the Second World War and later the architect of the Marshall Plan. He understood that power without discipline corrodes itself. The ship’s official motto, “Patience, Not Weakness,” captured that worldview precisely. The unofficial crew motto, less polished and far more sailorly, acknowledged the daily reality behind the ideal.

Construction began at Newport News Shipbuilding in March 1964. She was launched in May 1965, sponsored by Katherine Tupper Marshall, the General’s widow. At the ceremony, former Secretary of State Dean Acheson spoke bluntly about strategic balance, a reminder that this vessel was not about symbolism. When Marshall was commissioned on April 29, 1966, she entered a Navy that was already deep into the undersea chess match of the Cold War.

Her early patrols carried Polaris missiles and ranged across the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Arctic approaches. Forward deployment to Holy Loch in Scotland and Rota in Spain shortened transit times and extended deterrent coverage. Blue Nose patrols under Arctic ice were not stunts or bravado. They were proof of survivability and reach, reassurance to planners who needed to know that no corner of the ocean could negate the deterrent.

In December 1967, that abstract mission collided with physical reality. While submerged in the Mediterranean, George C. Marshall struck an unidentified submerged object. The impact tore open external ballast tanks on the port side, creating a breach approximately sixteen feet long and damaging associated structures, including high pressure air systems. The pressure hull remained intact. That fact alone justified years of conservative engineering and post-Thresher construction discipline.

The identity of the other vessel was never publicly confirmed. Later accounts frequently describe it as a Soviet submarine, a conclusion shaped by geography, timing, and the intensity of undersea operations in those waters. That suspicion has never been conclusively proven in open sources. What is certain is that the patrol was aborted and the submarine returned to Rota, Spain, with damage serious enough to require immediate attention.

Security restrictions ruled out the use of local dry dock facilities. What followed became one of the more remarkable technical episodes in Marshall’s career. The submarine tender Canopus fabricated a watertight cofferdam on its helicopter deck, then secured it to the damaged hull while the submarine remained afloat. The space was de watered, repairs were welded in place, and by mid January 1968 the submarine was returned to operational status. No announcements were made. The job was done, and the mission resumed.

The 1970s brought modernization. Beginning in 1971, George C. Marshall entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for conversion to the Poseidon C 3 missile system. Poseidon introduced MIRV capability, multiplying the strategic weight of each patrol. A successful demonstration and shakedown operation launch in April 1973 confirmed the upgrade, and the submarine returned to service carrying far more destructive potential than when she first went to sea.

Mid career operations followed a steady, professional rhythm. Patrols continued from Holy Loch and Rota. The Mediterranean remained crowded and unforgiving. Not every incident involved geopolitics. In the late 1970s, the submarine became entangled in a fishing trawler’s net, leaving a visible scar on the sail. More sobering was October 25, 1977, when scaffolding fell from a crane on Canopus at Rota, killing two crew members. Even in a service built on risk management, tragedy arrives uninvited.

Another major overhaul between 1981 and 1984 reflected evolving doctrine. Nuclear torpedo and SUBROC systems were removed. The Mobile Submarine Simulator decoy, MOSS, was installed in selected torpedo tubes, emphasizing survival against increasingly capable anti submarine forces. The Cold War had matured into a contest of sensors, patience, and endurance.

By the late 1980s, the long confrontation was visibly winding down, though few trusted appearances. George C. Marshall completed a total of 78 strategic deterrent patrols over her career. She operated in the Atlantic and Caribbean and conducted a final Arctic deployment in July 1990. She was among the last submarines to depart Holy Loch before the base closed, marking the quiet end of a chapter in naval history.

Her final dive occurred in 1992 off San Diego, a symbolic closing act before transiting to Bremerton, Washington. She was decommissioned and struck from the Naval Register on September 24, 1992. Recycling under the Navy’s nuclear ship and submarine program was completed in February 1994.

What remains are fragments and memories. Flags, patches, and a section of her hull are preserved by the George C. Marshall Foundation. More importantly, the record of her service endures. Thousands of sailors stood watch in narrow passageways, celebrated holidays underwater, and carried a burden few civilians ever see, all so that the unthinkable would remain theoretical.

The USS George C. Marshall did not win battles or make headlines. She did something far harder. She waited. She endured. She embodied the truth her motto implied, that patience, properly applied, is not weakness at all. It is power under control.

Leave a comment