The USS Woodrow Wilson belonged to a generation of submarines that were never meant to be seen, remembered, or celebrated in the usual way. She was built to disappear, to wait, and to make catastrophe unnecessary by making it inevitable in theory. As a Lafayette-class fleet ballistic missile submarine, she formed part of the original “Forty-One for Freedom,” the silent backbone of America’s sea-based nuclear deterrent during the most dangerous decades of the Cold War.

What makes Woodrow Wilson stand apart is not simply the length of her service, more than three decades, or the seventy-one strategic deterrent patrols she completed. It is the shape of that service. Few submarines lived three distinct operational lives. Fewer still did so successfully. From Polaris patrols, to Poseidon MIRV deterrence, to an improbable final career as a special operations attack submarine, Woodrow Wilson adapted to history rather than being discarded by it.

She was also the only United States Navy ship ever named for the 28th President, a man whose own legacy was marked by idealism, contradiction, and transformation. The parallel is unintentional, but fitting.

Forged at Mare Island

The Woodrow Wilson was a product of deliberate foresight. She belonged to the Lafayette class, hull design SCB-216, a refinement of earlier ballistic missile submarines that incorporated one crucial lesson learned from rapid technological change. Her missile tubes were built larger than necessary for the Polaris missiles she initially carried, allowing room for future upgrades that designers knew would be inevitable.

She measured 425 feet in length, with a beam of 33 feet, and displaced approximately 8,250 tons submerged. Propulsion came from a single S5W pressurized-water nuclear reactor driving two General Electric geared turbines, a configuration that had proven reliable across multiple submarine classes.

Construction began at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California, where her keel was laid on September 13, 1961. The work was not without incident. On May 8, 1963, a heavy electrical cable contacted a switchboard, igniting a fire that injured three shipyard workers. The damage was limited, but the event served as a reminder that even in peacetime, submarine construction carried real risk.

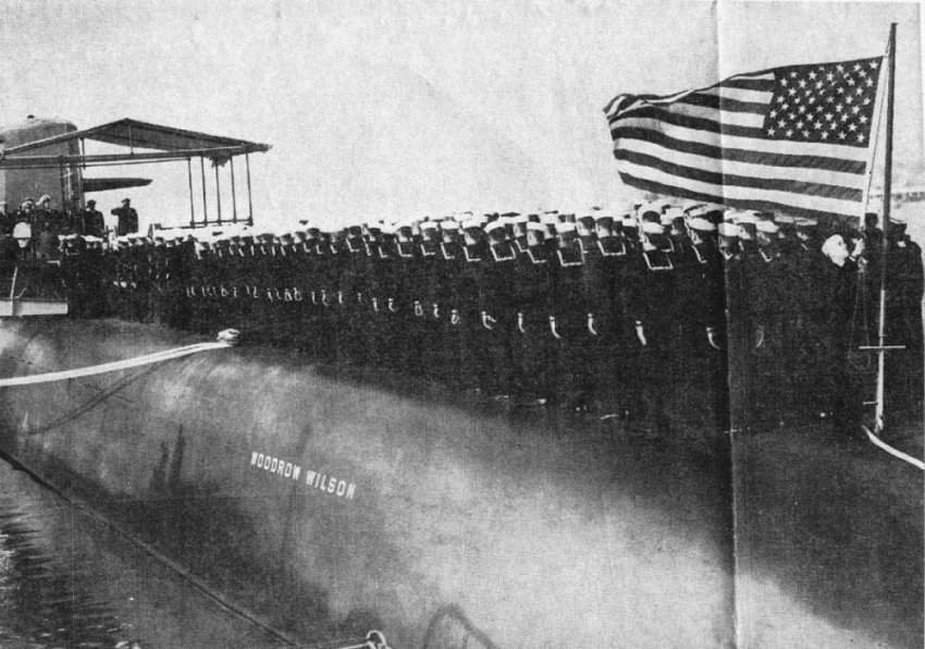

She was launched on February 22, 1963, sponsored by Miss Eleanor Axson Sayre, the granddaughter of President Woodrow Wilson. Commissioning followed on December 27, 1963. Command responsibility reflected the dual-crew system standard for ballistic missile submarines. Commander Cleo N. Mitchell assumed command of the Blue Crew, while Commander Walter N. Dietzen led the Gold Crew.

The submarine entered service built for a single mission. History would soon require more.

A Tense Passage into the Cold War

Barely a month after commissioning, Woodrow Wilson received orders that would test her crew before her first patrol even began. Departing the West Coast on January 9, 1964, she was transferred to the Atlantic Fleet, a move that required transit through the Panama Canal.

The timing could not have been worse. When the submarine arrived at the canal on January 19, Panama was engulfed in violent anti-American riots. The transit became a security operation as much as a navigational one. U.S. Marines and Army soldiers provided heavy guard along the route, weapons visible, nerves tight.

Despite the tension, the transit was completed in a record seven hours and ten minutes. The passage was swift, controlled, and deliberate. It also marked the real beginning of Woodrow Wilson’s operational life. This was not a ceremonial transfer. It was a reminder that even the movement of a submarine could carry strategic weight.

Polaris Patrols and the First Watch

The submarine commenced her first strategic deterrent patrol in June 1964, operating out of Charleston, South Carolina. Armed with Polaris A2 missiles, she became part of the continuous at-sea presence designed to ensure that no adversary could ever count on a disarming first strike.

Forward operations soon followed. Woodrow Wilson deployed from Rota, Spain, and Holy Loch, Scotland, key nodes in the Atlantic deterrent network. These patrols were monotonous by design. Silence, routine, and precision defined daily life. Success was measured by absence. Nothing happened, and that was the point.

In 1968, the submarine entered a 13-month overhaul at Newport News Shipbuilding. The purpose was not maintenance alone, but transformation. She emerged equipped with the Polaris A3 missile system, extending her reach and keeping pace with the evolving nuclear balance.

In late 1969, Woodrow Wilson shifted theaters. Transferring to the Pacific Fleet, she arrived at Pearl Harbor in November before moving on to Apra Harbor, Guam. The Cold War was global, and so was her watch.

Around 1970, during this Pacific service, the crew faced a casualty that tested discipline and ingenuity. Water intrusion in the maneuvering room threatened the main motor mounts. With no mechanical solution immediately available, sailors formed what became known as the “bucket brigade,” manually moving water from the maneuvering room to the torpedo room. It was not elegant, but it worked. The incident never appeared in headlines, and that too was characteristic of the service.

The Poseidon Era Begins

In 1972, Woodrow Wilson returned to the Atlantic for another major conversion at Newport News. This time, the change was profound. She was refitted to carry the Poseidon C3 missile system, introducing Multiple Independently Targetable Reentry Vehicle capability. One missile now carried multiple warheads, each capable of striking a separate target.

The submarine resumed deterrent patrols in August 1976, now as part of a far more complex strategic equation. The Poseidon system remained her primary armament for the rest of her ballistic missile career.

It is important to note what did not happen. Unlike the later James Madison and Benjamin Franklin class submarines, Woodrow Wilson and her Lafayette class sisters were never upgraded to carry the Trident I C4 missile. She retained the Poseidon C3 system until the end of her strategic service, a fact sometimes misunderstood in retrospective accounts.

Her performance with Poseidon was not theoretical. She conducted successful Follow-on Operational Tests of the C3 system, including missile launches in 1977 and again in 1983. These tests confirmed both crew proficiency and system reliability.

Operational life was not without incident. On June 4, 1979, Woodrow Wilson ran aground near Race Rock, outside New London, Connecticut, in heavy fog. The submarine freed herself without sustaining major structural damage, a testament to careful handling under pressure.

In 1989, during her final refueling overhaul in Charleston, Hurricane Hugo struck the region. Rather than retreat behind the gates of the shipyard, the crew assisted with local recovery efforts. For this work, they were awarded the Humanitarian Service Medal. Even a strategic deterrent submarine could, at times, serve more immediate human needs.

A New Mission in a Changed World

By 1990, the Cold War order that had defined Woodrow Wilson’s existence was collapsing. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty imposed limits that made older ballistic missile submarines redundant. Many were destined for early retirement.

Woodrow Wilson was given another chance.

In June 1990, her sixteen missile tubes were permanently deactivated using cement and steel plugs. She was reclassified from SSBN-624 to SSN-624, transforming from a strategic missile platform into an attack submarine. The dual-crew system ended, replaced by a single consolidated crew.

Skepticism was inevitable. A submarine designed around missile patrols was now expected to compete in anti-submarine warfare. The crew answered the question quickly. During shakedown, Woodrow Wilson achieved a perfect eleven-for-eleven score in torpedo firing exercises against maneuvering targets. She earned the White “A” for excellence in anti-submarine warfare, an unmistakable endorsement.

The transformation did not stop there. The former missile compartment was reconfigured to support special operations forces. Berthing space was added. Equipment storage was created, including space for combat rubber raiding craft. Lock-out capabilities allowed Navy SEALs to deploy and recover while the submarine remained submerged.

In September 1991, Woodrow Wilson participated in Exercise Phantom Shadow, the largest joint Navy and Special Warfare exercise of its time. She carried more than 130 special operations troops and helped validate new post-Cold War tactical concepts. The exercise proved that converted SSBNs could serve as effective clandestine platforms in littoral environments.

For a submarine built to wait silently under the polar ice, it was an unexpected but successful final act.

The Long Goodbye

The end came quietly. Woodrow Wilson was deactivated in September 1993 and formally decommissioned on September 1, 1994. She was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register the same day.

Her final voyage echoed her first Atlantic transfer. Towed by the salvage ship USS Salvor, she passed through the Panama Canal one last time, bound for Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington.

On September 26, 1997, she entered the Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program. Recycling was completed on October 27, 1998. The hull was dismantled. The reactor compartment was removed. The submarine ceased to exist as a vessel.

What Remains

The identity of Woodrow Wilson did not vanish with her hull. Her sail and upper rudder were preserved and now stand at Deterrent Park at Naval Base Kitsap, Bangor, Washington. They serve as a monument to the ballistic missile submarine force and the quiet labor that underwrote nuclear stability for decades.

Inside the sail exhibit, the periscopes come from USS Kamehameha, another converted SSBN, linking the legacies of submarines that adapted rather than faded away.

In total, Woodrow Wilson completed seventy-one strategic deterrent patrols. She served as both a fleet ballistic missile submarine and a special operations attack submarine. She bridged the Cold War and its aftermath, proving that even the most specialized machines can find new purpose when history shifts beneath them.

That, in the end, may be her most enduring lesson.

Leave a comment