There are moments in naval history when the line between chaos and calculation becomes so thin that no amount of hindsight can separate them. December of 1944 was a month full of such moments, a time when the Pacific had become a kind of cosmic joke told in a language only submariners understood. If the Hitchhikers Guide had ever been foolish enough to publish a chapter on the American submarine campaign, it might have described those boats as improbable machines crewed by improbable men who somehow made logic work underwater. It would then likely note that the worst poetry in the universe had nothing on the way the ocean recited explosions back to the hull of a submarine in the pre dawn hours.

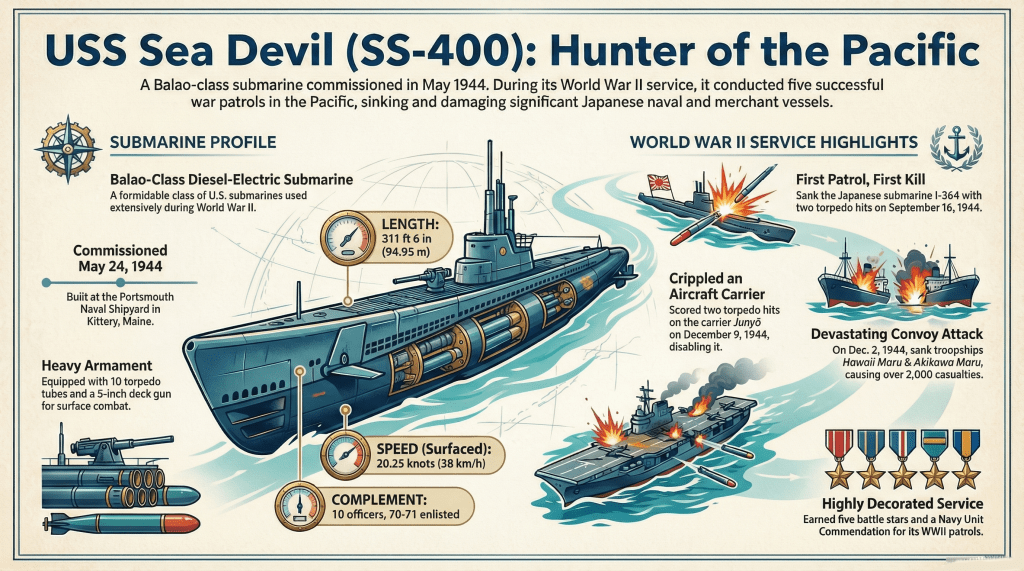

USS Sea Devil was one of those improbable machines. She was a Balao class boat, new enough to still have the sharp edges of the shipyard on her fittings, seasoned enough on her second patrol to know that the Pacific did not care how many drills she had passed. Lieutenant Commander Ralph C. Style commanded her. He had the kind of temperament that resisted melodrama. He understood that a submarine captain lived in the narrow space between what the ocean allowed and what an enemy convoy failed to notice. His job on the night of 1 December rolling into 2 December was simple on paper. He was to hunt. In reality, he was to wrestle with a convoy, the weather, and the limits of human nerves.

Late on the night of 1 December, Sea Devil made contact with a distant formation. The SJ radar saw it first. The boat shifted course at 0239, beginning a closing approach that would become something closer to a trial by water. One minute after that course change, while running on the surface in seas that had grown testy and unpredictable, a tremendous wave lunged across the bridge. It hit with a violence that no training film ever adequately showed. The starboard lookout was knocked completely off the periscope shears and onto the bridge deck. He suffered a laceration and what the log dryly described as possible fractured ribs. The ocean does not grade on a curve.

The real trouble came when that same wave forced water down the main induction. A submarine lives by its ability to keep water out of the places where men and machinery occupy the same narrow space. When water pours into both engine rooms, the after battery, the crew’s mess, the radio shack, and the control room, that sense of order becomes a distant memory. For several minutes, the boat was less a warship and more a stubborn steel cylinder refusing to drown. The crew fought the flooding with the kind of instinct that only comes from training and the unspoken desire to see another sunrise. They made the boat tight again. Electrical grounds were everywhere, but the hull remained alive.

By 0320, Sea Devil had steadied herself. She was now in position, twelve thousand yards ahead and three thousand yards off the port track of the convoy. The silhouettes of ships moved across the darkness like a grim procession. Eleven targets were noted, a mixture of transports and escorts. It was the kind of sight that could make even a seasoned captain inhale slowly. It promised opportunity. It also promised trouble.

At 0322 the forward lookouts spotted a spherical shape drifting less than one hundred yards off the bow. It was a floating mine. If the universe wished to test the composure of the boat, it was doing so with creativity. Sea Devil swung right with full rudder, sliding past the mine with the indifference of a matador sidestepping a bull. There are few things as unsettling in the dark as the sudden realization that the sea is littered with explosives seeking company.

At 0332 the boat submerged and began her approach. It was the moment when the surface world gives way to the strange interior calm of a submarine on the hunt. A few minutes later Sea Devil came up to radar depth for a sweep, but the seas broached the boat unpredictably. Style abandoned the attempt and committed to tracking by bearings alone. It was lonely work. It required a patience usually reserved for monks and watchmakers.

At 0400 the moon clouded over. Periscope visibility worsened. The weather report in the log was clinical, yet anyone who has ever tried to find a convoy in mixed seas knows that the boat becomes a kind of blind animal relying on instinct and occasional luck. Sea Devil had to maintain standard speed in order to keep her depth steady. It was a juggling act performed in pitch black water.

At 0413 an escort passed close off the beam. It was pinging steadily. The log noted the pinging with impressive calm. Sound conditions were poor. Pings in poor conditions behave like unwelcome guests at a party. They drift, ricochet, and confuse. They also remind a submarine that an enemy warship is close enough to ruin the night.

At 0414 Sea Devil struck first. She fired four Mark 18 torpedoes from her bow tubes at what the log called a medium size freighter. The range was about three thousand yards. The gyros were set. The solutions were good. All four torpedoes missed. In the museum of submarine history there should be a glass case labeled The Torpedoes That Should Have Hit but Did Not. It would be a large case.

Style did not linger on disappointment. Ten minutes later, at 0424, he ordered the stern tubes brought into play. Tubes five and six. This time the target was a very large tanker that presented itself at a range of six hundred yards. The track was one thousand fifty port. The gyros were set. The torpedoes ran true.

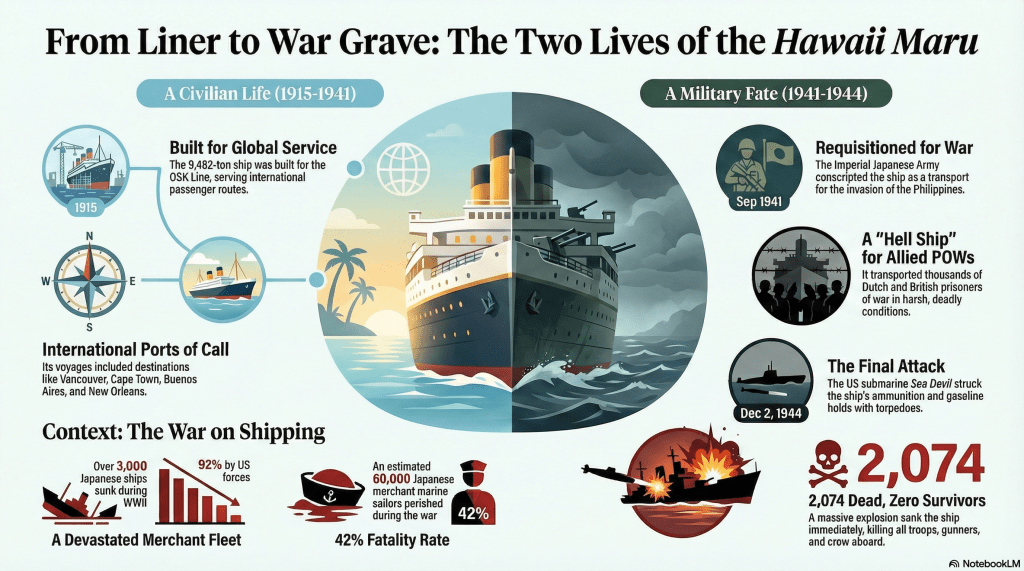

At 0424:50 the log recorded it. Two observed and timed hits. A huge column of debris thrown into the air. That clean phrase from the patrol report does not capture the sight itself. Submariners never forget the illumination of an explosion underwater. It lights the sea from within, an inverted thunderclap made of fire and water. The ship that Sea Devil struck was Hawaii Maru, though the log did not yet record her name. It only recorded her death.

At 0425 Sea Devil swung right to avoid an escort ahead of the center column. Such maneuvers become instinctual. When a ship explodes, escorts often behave like hornets. They run toward the noise. A submarine cannot afford to be the thing that meets them there.

At 0427 the log noted that the tanker was sinking fast. Water engulfed the deck. The moonlight, filtered through cloud and smoke, reflected off the breaking waves. It was the grim announcement that more than two thousand men were about to vanish into the Pacific.

Hawaii Maru was carrying soldiers, gunners, and crewmen. She was also carrying ammunition and gasoline. When the torpedoes struck her forward, the explosion set off the ammunition in the second hold. That explosion then ignited the gasoline stowed aft. The resulting blast was catastrophic. There was no time for lifeboats. There was no hope for survivors. By the time Sea Devil watched the water sweep across her deck, the ship’s fate was sealed.

At 0428 another pinger passed close aboard on the port side. The escorts were closing. The log’s language remained calm but the tension in that compartment must have been rising. Submariners often speak of that strange duality. Their hands move with precision while their minds race.

At 0429, while the wreck of Hawaii Maru still churned the sea behind them, Sea Devil found a second target. The boat fired four Mark 23 torpedoes from her stern tubes at a large freighter or transport, later known to be Akikawa Maru. The range was thirteen hundred yards. The track was one thousand degrees port. The gyros were set. The depth was ten feet. While the torpedoes were running, Style raised the periscope. A massive freighter in the center column was now less than one hundred fifty yards away heading directly for the boat. There are few phrases in a patrol report that have the power to chill the imagination quite like that one. One hundred fifty yards in a submarine feels like touching distance. Style ordered deep submergence.

At 0430 the explosions arrived. The torpedoes struck the second target. The blast was powerful enough to shake the boat. The log noted that debris fell directly overhead. It sounded possible that the ship carried ammunition. There was no poetry in that moment. Just noise and shock and the knowledge that the Pacific had claimed another set of lives.

At 0432 the crew could hear the breaking up noises of the ship very plainly. At 0433 they heard more breaking up noises on the bearing of the ammunition ship. The ocean telegraphed the sound of steel folding inward like a dying bell.

At 0435 the boat reported screws and pinging all over the dial on three sound gears. Escorts were hunting for them with the desperation of cornered animals. Sea Devil leveled off at five hundred feet and rigged for depth charge. That simple phrase marked the beginning of a ritual every wartime submarine knew well. A submarine in depth charge conditions becomes a cramped cathedral. You listen to the ocean speak in detonations. You feel the timbers of the boat shudder with each near miss. You wonder if a bolt that was tight yesterday is still tight today.

At 0440 twelve depth charges exploded, none too close. Escorts milled around overhead. That phrase, none too close, always hides a world of stress. A depth charge is loud even when it is far away. It is deafening when it is near. The men aboard Sea Devil sat through it with the restraint of professionals and the hope that the next one would be farther, not closer.

At 0510 the screws faded. At 0535 Sea Devil surfaced. The SJ radar picked up three escorts at eight thousand yards. The boat set course for its station. There was still work to be done.

What the patrol report could not say, but what must be understood, is that in the space of one hour and sixteen minutes, the crew of Sea Devil had destroyed two large ships, triggered a series of catastrophic explosions, evaded escorts, and survived the kind of actions that leave lasting marks on the mind. The ocean swallowed Hawaii Maru and Akikawa Maru, along with thousands of men who would not return home. The submarine sailed on, her crew exhausted, her captain mindful of the weight that victory often carried.

It is tempting to look back on that night with the confidence that comes from knowing how the war ended. It is tempting to imagine that Sea Devil acted from a position of inevitability. That is not true. In December 1944 the Pacific was still a vast arena of risk. Every attack required nerve and judgment. Every decision carried with it the possibility of disaster. Submarines lived on the fine edge between success and loss. Sea Devil succeeded because her crew was skilled, her captain was calm, and a measure of luck tilted her way.

People often ask what made submarine warfare so distinctive. The answer lies in the quiet parts. It lies in the moments between torpedo launches. It lies in the discipline shown while lying deep, listening to depth charges. It lies in the whispered comments in the control room that never made it into the formal patrol report. It lies in the fact that the men aboard Sea Devil had no illusions about what they were doing or why.

The sinking of Hawaii Maru stands out for its scale and tragedy. More than two thousand men were lost in a matter of minutes. The official Japanese record called it zenmetsu, complete annihilation. That word carries a sorrow that transcends national lines. It is the honest acknowledgment that war destroys lives with brutal indifference.

Sea Devil did not pause to reflect. She continued her patrol. Later, she damaged the carrier Junyo. She would earn five battle stars before the war was over. Her crew would return home. Some would talk. Most would not. Submariners carried their stories quietly, as if volume itself might diminish accuracy.

The historian who walks back into the events of December 2 finds no tidy moral. There is no easy lesson. There is only the reality that war forces choices and that those choices create consequences that endure long after the ocean calms again. The log of Sea Devil recorded events with simplicity because the men aboard did not have time for philosophy. They had time only for decisions.

In the end, what remains is the story itself. A submarine, a convoy, a night of violence on the open sea. A wave that nearly disabled a boat. A mine that drifted too close. Torpedoes that missed. Torpedoes that struck. Ships that exploded. Escorts that hunted without success. And beneath all of it, the quiet endurance of a crew that trusted one another and did their duty.

If there is any wisdom to be taken from that night, it is the recognition that history is usually carried forward by people who rarely appear in textbooks. It is built by sailors who fought flooding with their bare hands. By lookouts who stood watch on pitching decks. By officers who kept their voices steady when the pingers grew louder. By men who listened to steel break apart in the dark and prayed they would not hear the same sound from their own hull.

The Pacific eventually forgot the fires of that night. The waves rolled back to their usual rhythms. Time washed over the coordinates where Hawaii Maru sank. Yet the story remains. It remains in the patrol report. It remains in the recollections of those who study naval history. It remains in the understanding that courage is often quiet and that survival at sea depends on skill, resolve, and the strange mercy of chance.

USS Sea Devil surfaced on the morning of 2 December and resumed her patrol. The war did not pause. The ocean did not pause. Only the narrative pauses, long enough for us to walk that forgotten hallway and see the fingerprints left behind by the men who lived it.

And then it moves on, as history always does.

Blair, Clay. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975.

CombinedFleet.com. “IJA Transport Hawaii Maru.” Accessed November 2024. https://www.combinedfleet.com/Hawaii_t.htm

CombinedFleet.com. “USS Sea Devil (SS-400) Tabular Record of Movement.” Accessed November 2024. https://www.combinedfleet.com/ss-400.htm

Cressman, Robert J. The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1999.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. 10: The Atlantic Battle Won. Boston: Little, Brown, 1957.

Nofi, Albert A. To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940. Newport: Naval War College Press, 2010.

U.S. Navy. War Patrol Report, USS Sea Devil (SS-400), Second War Patrol (December 1944). National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 38.

Willmott, H. P. The War with Japan: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1931–1945. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1982.