The USS Daniel Boone was born into a world balanced on the edge of annihilation. When her keel was laid down on February 6, 1962, at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a Cold War that relied as much on unseen submarines as on visible missiles and soldiers. The Navy’s new fleet ballistic missile program had already begun to take shape, and the Boone was part of that second generation of boats that would carry America’s most destructive weapons into the deep. She was designed to remain hidden, to roam the world’s oceans in silence, unseen but always present, serving as a reminder that any attack on the United States would come with unbearable consequences.

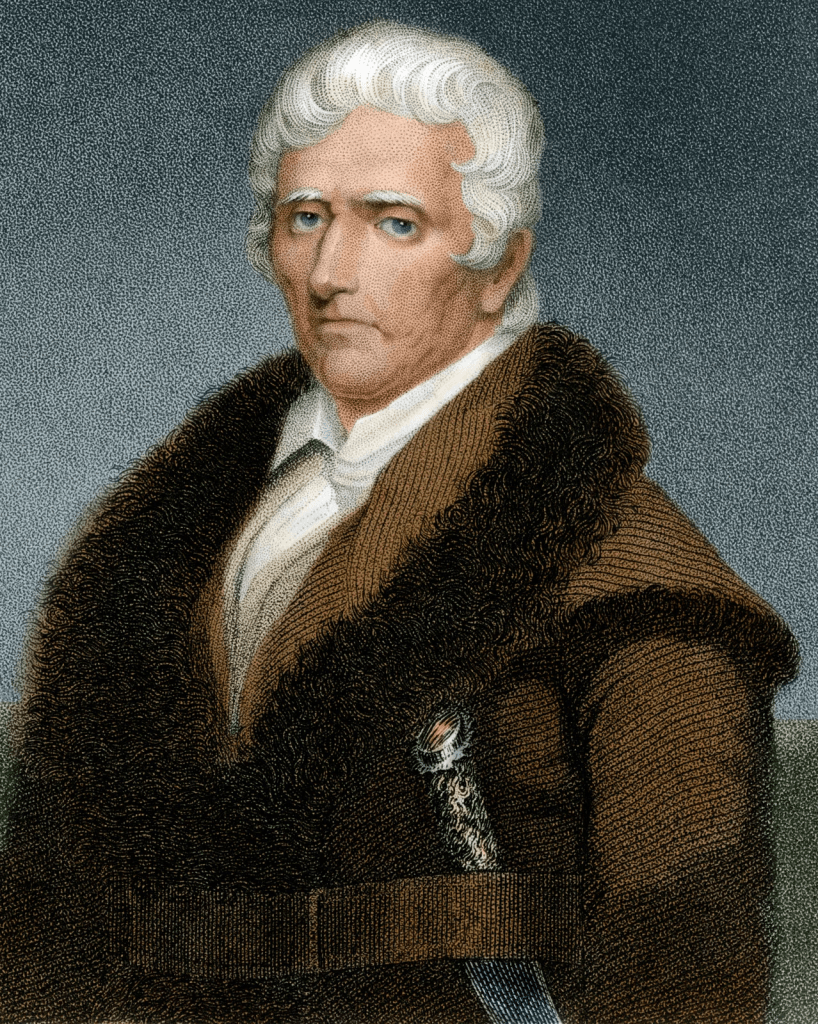

The USS Daniel Boone took her name from one of America’s most enduring legends, the frontiersman Daniel Boone. Born on November 2, 1734, in Pennsylvania, Boone became a symbol of courage, exploration, and rugged independence. He blazed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap, opening the way for settlers into Kentucky, and his adventures in the American frontier made him a folk hero even in his own lifetime. Boone fought in the French and Indian War and later in the Revolutionary War, defending frontier settlements against British-allied forces. Though often romanticized in later tales, the real Boone was a man of endurance and adaptability, traits that mirrored the submarine that bore his name. Just as the frontiersman explored uncharted lands to secure a future for his people, the submarine Daniel Boone explored the depths of the sea to safeguard a nation standing watch in an uncertain age.

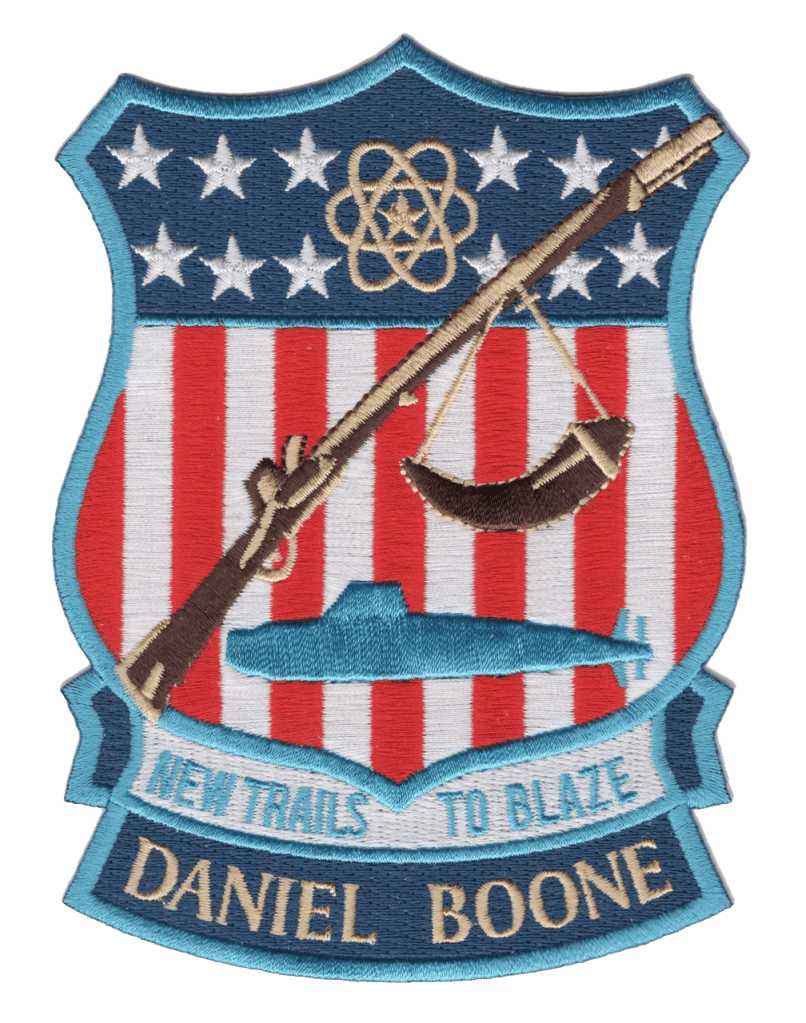

Named after the famous American frontiersman Daniel Boone, the submarine embodied a spirit of exploration and self-reliance that fit her mission. She was launched on June 22, 1963, with Mrs. Margaret A. Cooper, wife of Senator John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, serving as her sponsor. On April 23, 1964, she was commissioned into service under the command of Captain George P. Steele for the Blue Crew and Commander William M. Hines for the Gold Crew. These two alternating crews allowed her to maintain near-constant deterrent patrols, keeping her at sea while one crew trained and refitted ashore. This system of dual manning was essential to maintaining the country’s nuclear readiness, ensuring that submarines like the Boone were almost always on station somewhere in the vastness of the Atlantic or Pacific.

The Daniel Boone was the ninth boat in the James Madison class, itself a refinement of the Lafayette class, which represented the backbone of America’s “41 for Freedom” deterrent fleet. She carried sixteen Polaris A3 ballistic missiles, each capable of delivering a nuclear warhead with precision to targets thousands of miles away. Her initial patrols began in August 1964, and she was soon permanently assigned to the Pacific Fleet. This marked a shift in U.S. naval posture, ensuring that ballistic missile coverage extended to the western Pacific as a counterbalance to Soviet influence in Asia. For the crew, these patrols meant long months of monotony punctuated by drills and maintenance. They operated in the twilight of secrecy, forbidden from speaking about where they went or what they carried, but each patrol was a crucial link in a chain of deterrence that kept the peace through fear of the unthinkable.

By the late 1960s, the rapid pace of missile development made upgrades inevitable. The Navy began converting the original Polaris boats to carry the new Poseidon C3 missiles, which offered greater range, accuracy, and multiple warhead capability. The Daniel Boone entered Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in July 1971 for an extensive overhaul that included nuclear refueling and the Poseidon conversion. When she rejoined the fleet in late 1972, she emerged more powerful than before, her missile system upgraded and her life extended. The overhaul marked her transition from the first generation of ballistic missile submarines to the second, ensuring she would remain relevant well into the 1980s.

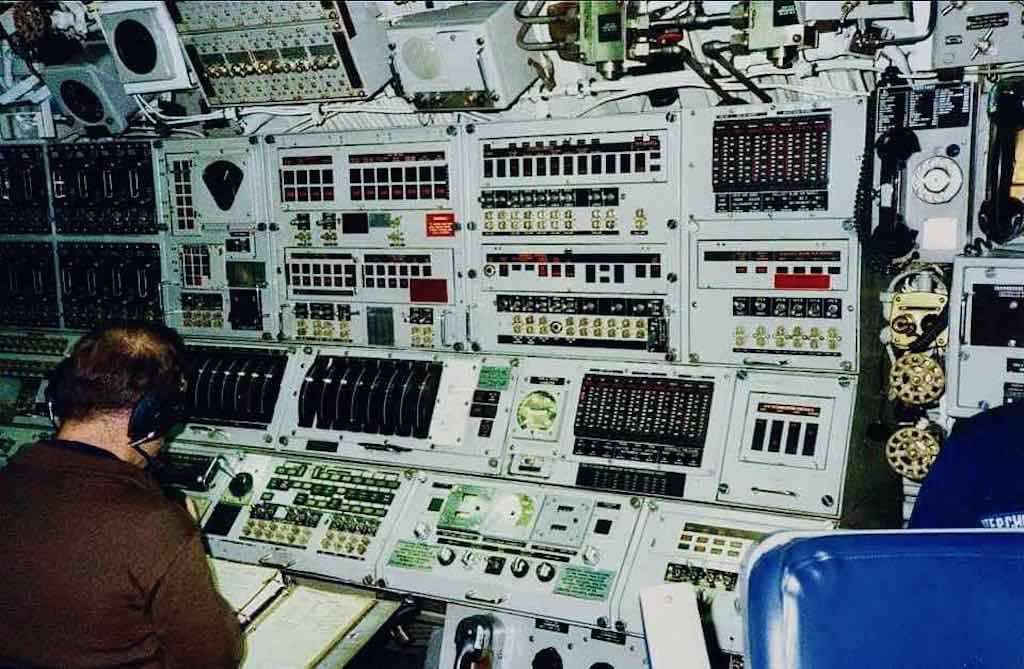

Her post-overhaul years saw a return to the relentless rhythm of deterrent patrols, alternating crews, and quiet service. Like her sister ships, the Boone’s life at sea was defined by routine: drills, maintenance, sonar monitoring, and endless watch rotations. The ocean became her constant companion, her crew’s isolation broken only by radio messages from home or the occasional periscope observation of a distant coastline. Few outside the submarine force ever saw her, and fewer still understood what life was like aboard. The men who served on her did not fight battles or fire weapons in anger, but their presence and readiness played a major role in ensuring that others never had to.

By 1978 the Boone had completed dozens of deterrent patrols, and the Navy began preparing for another round of modernization. The strategic landscape was changing again, and with the introduction of the Trident missile system, the older Poseidon-equipped boats would eventually need to adapt or retire. The Daniel Boone’s hull was strong, her reactor reliable, and her systems adaptable enough to warrant conversion. In 1979 she entered another overhaul to prepare for the installation of the Trident I C4 missile, a system capable of striking targets even deeper inside enemy territory with far greater accuracy. When she successfully launched a Trident I C4 missile off Cape Canaveral in 1980, she became the first operational fleet ballistic missile submarine to carry and fire that weapon. The achievement marked another chapter in her evolution, confirming her place in the front rank of deterrent forces for the next decade.

Through the 1980s the Daniel Boone continued her patrols, now equipped with the most advanced missiles in the world. The Cold War reached new peaks of tension during this time, and ballistic missile submarines like the Boone formed the silent heart of America’s nuclear strategy. Their ability to remain hidden beneath the waves for months made them the most survivable leg of the nuclear triad. The Boone’s crew maintained the highest standards of performance, knowing that even a single mistake could compromise her secrecy or her deterrent posture. Her patrols were measured not in miles traveled but in days submerged and readiness maintained. She completed her fiftieth patrol by September 1981, a milestone that few vessels achieved.

By the late 1980s, the global situation began to shift. The Soviet Union was weakening, and arms control treaties began to reshape the nuclear balance. For boats like the Boone, that meant fewer patrols and more time in port. In January 1986 she returned to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for another overhaul, this one intended to extend her service life and ensure safety and reliability. When she left the yard in 1988, she resumed deterrent operations, but it was clear that the era of the “41 for Freedom” was drawing to a close. The newer Ohio-class submarines, carrying the much larger Trident II D5 missile, were beginning to replace the older boats. The Boone, though still capable and reliable, was a veteran of a different age.

In April 1991, she celebrated twenty-five years of service, a quarter-century of silent vigilance beneath the seas. Only a handful of her contemporaries could boast such longevity. Later that year, she completed her final strategic deterrent patrol, marking the end of her primary mission. By that time, the Soviet Union was collapsing, and the world that had given rise to her existence was vanishing. The U.S. Navy began converting some older submarines for new roles, including special operations support, but the Boone’s fate would be different. After nearly three decades of service, the decision was made to retire her.

The Daniel Boone was decommissioned on February 18, 1994, and entered the Navy’s nuclear ship and submarine recycling program at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. The process of dismantling her was careful and deliberate, ensuring that her reactor was safely removed and her materials recycled or disposed of properly. The recycling was completed on November 4, 1994, marking the end of a vessel that had once represented the cutting edge of American deterrence. Her name and legacy, however, remained a part of naval history and the collective memory of those who served aboard her.

The Boone’s service encapsulates the history of an entire era of undersea warfare. From the Polaris to the Poseidon to the Trident, she carried three generations of nuclear missiles and three generations of sailors. She patrolled during the height of Cold War tensions, when the very survival of the planet depended on the balance of fear, and she continued through the period of détente and arms reduction that followed. Her transformation over the decades mirrored the evolution of U.S. strategic doctrine itself, moving from a simple deterrent posture to a more complex, flexible system of global readiness. Yet through all of it, her mission remained constant: to deter war by existing as a threat so potent that no rational enemy would risk provoking it.

Those who served aboard the Daniel Boone often describe her not in terms of weaponry or strategy but in human terms. They speak of the cramped living conditions, the smell of machinery and oil, the endless hum of the reactor, the subtle roll of the sea even hundreds of feet below the surface. They remember long weeks without sunlight, the close camaraderie of the crew, the rare joy of a letter from home. They remember the pride of surfacing after a successful patrol, knowing that their unseen presence had played a small part in keeping the peace. For many submariners, the Boone was more than a weapon; she was a home, a brotherhood, and a way of life.

The name Daniel Boone was a fitting one. The original Boone was a pioneer who explored the frontier and helped open a new world for America. The submarine that bore his name explored a different frontier, one of silence and darkness beneath the seas. Both represented courage and endurance in the face of uncertainty. Both pushed boundaries in their own ways. The USS Daniel Boone carried her name proudly, symbolizing the blend of technical mastery and human resolve that defined the U.S. Navy’s submarine force.

In the years since her dismantling, the memory of the Boone endures among veterans and naval historians. Her photographs appear in archives and museums, her patrol logs are studied by students of naval strategy, and her name lives on in reunion groups and oral histories. The story of the Boone is the story of America’s Cold War under the waves, a tale of technology, discipline, and quiet strength. It reminds us that deterrence is not simply about weapons but about the people who operated them, who trained, maintained, and sailed them in conditions few civilians could imagine.

The ocean keeps its secrets well, but history does not forget those who served beneath it. The USS Daniel Boone was one of the most successful and enduring ballistic missile submarines of her generation. Her thirty years of service reflect the evolution of naval technology, the resilience of her crews, and the strategic necessity of the submarine deterrent. Though she now rests only in memory and in records, her legacy continues to echo in the modern fleet. The sailors who now patrol aboard the Ohio and Columbia-class submarines are the inheritors of her tradition. Like her, they sail in silence, their mission understood by few but vital to many. The Boone’s story remains a testament to the silent service and to the enduring power of deterrence in preserving peace through readiness.

Facebook – The Photo History of the USS Daniel Boone

The Quarterdeck Website – USS Daniel Boone

Here’s the full list of citations formatted in Chicago style, suitable for your Dave Does History article or podcast documentation:

Sources

- Naval History and Heritage Command. “USS Daniel Boone (SSBN-629).” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/d/daniel-boone-ssbn-629.html.

- NavSource Naval History. “USS Daniel Boone (SSBN-629) Photo Archive.” NavSource Online Submarine Photo Archive. Accessed October 30, 2025. http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08629.htm.

- NavySite.de. “USS Daniel Boone (SSBN 629).” U.S. Navy Ships Information. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.navysite.de/ssbn/ssbn629.htm.

- Wikipedia. “USS Daniel Boone (SSBN-629).” Last modified October 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Daniel_Boone_(SSBN-629).

- National Park Service. “Daniel Boone.” American Revolution Biographies. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/people/daniel-boone.htm.

- Kentucky Historical Society. “Daniel Boone: Kentucky Pioneer.” Accessed October 30, 2025. https://history.ky.gov/exhibits/daniel-boone-kentucky-pioneer.

- Newport News Shipbuilding Archives. “Conversion of Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarines: Poseidon C-3 and Trident I C-4 Upgrades.” Shipyard Modernization Records, 1971–1980.

- All Hands Magazine. “Boone Joins Missile Fleet.” August 1964. U.S. Navy Bureau of Naval Personnel.

- National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). “Fleet Ballistic Missile Program: ‘41 for Freedom’ Submarine Class Records.” Record Group 181, Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

- Naval Submarine League. “Trident Program Milestones: First C4 Launches.” Undersea Warfare Journal 10, no. 3 (2000).

Leave a comment