When the USS Theodore Roosevelt slid down the ways at Mare Island Naval Shipyard on October 3, 1959, she carried more than a name from a boisterous past president. She embodied a new kind of American power, one that hid beneath the sea, silent and ready. She was the nation’s fourth ballistic missile submarine, part of a new deterrent fleet that would prowl the deep through the Cold War years. To her builders and crew she was not just a ship but a symbol of vigilance. To the Navy, she was a complex experiment in how to keep peace through fear.

Theodore Roosevelt, born on October 27, 1858, in New York City, was a man of boundless energy and ambition. A sickly child, he overcame severe asthma through vigorous exercise and outdoor activities, which sparked a lifelong passion for the outdoors. As a young man, he pursued a variety of interests, including natural history, politics, and public service. He served as the 26th president of the United States from 1901 to 1909, known for his progressive policies, trust-busting, and expansion of the national parks system. Roosevelt was also a war hero, famously leading the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War. His legacy extends beyond his presidency, as he became a symbol of American strength, resilience, and the spirit of adventure. His contributions to the nation’s development, both politically and environmentally, were immense, and his name would later be immortalized on one of the U.S. Navy’s most significant nuclear-powered submarines.

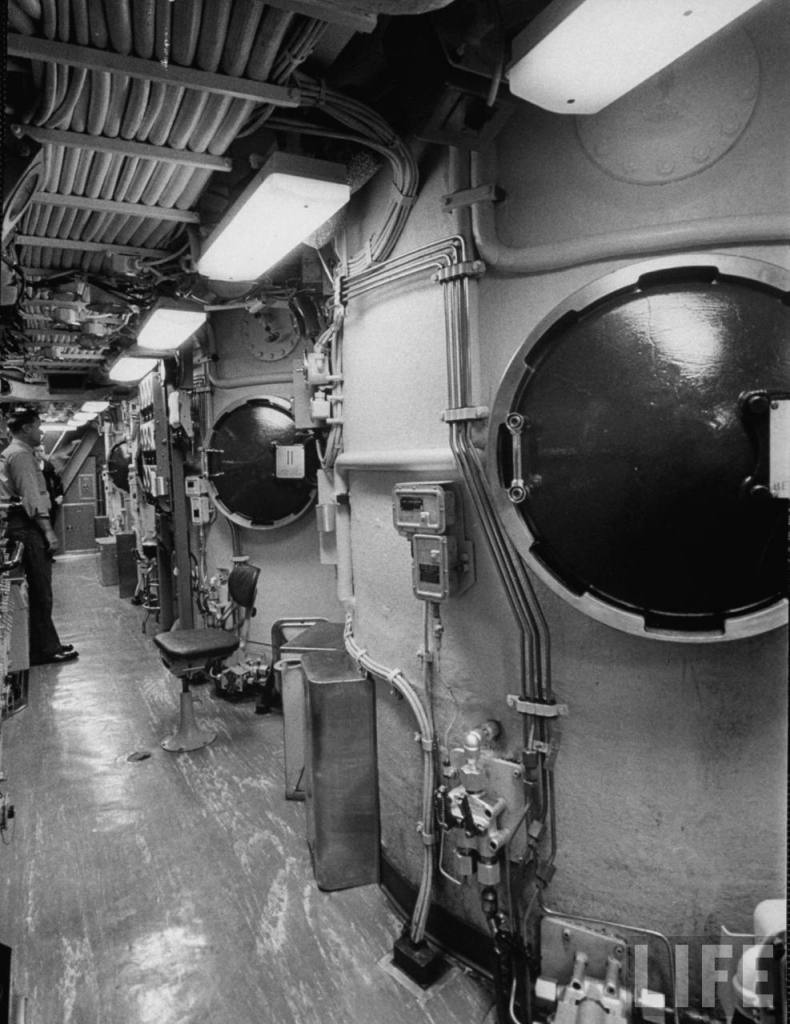

Commissioned on February 13, 1961, with Commander William E. Simpson Jr. in command of the Blue Crew and Commander Oliver H. Perry Jr. commanding the Gold Crew, the Theodore Roosevelt began her service during one of the most tense periods of the nuclear age. The Navy’s Fleet Ballistic Missile program was barely two years old, yet already the United States was racing to deploy a second-generation deterrent force capable of carrying the new Polaris A-1 missile. She was 410 feet long, displaced about 6,700 tons submerged, and could carry sixteen of those missiles in their launch tubes. The hull form was based on the Skipjack class attack submarines, giving her greater speed and maneuverability than the earlier George Washington class.

Her shakedown cruise took her through the Panama Canal to the Atlantic, where she became the first Fleet Ballistic Missile submarine to transit that narrow passage. The image of a nuclear-armed vessel passing under the gaze of the old locks symbolized a world in transition. Once she reached the Atlantic, the Theodore Roosevelt began workups out of Charleston and Cape Canaveral. Each missile launch was a blend of tension and precision, the crew practicing routines that had to work flawlessly in the event of real war.

By late 1961 she joined Submarine Squadron 14, operating out of Holy Loch, Scotland. This forward base became the nerve center for the U.S. Navy’s undersea deterrent in Europe. At Holy Loch, she rotated between her Blue and Gold crews, one taking the boat on patrol while the other rested and trained ashore. Those patrols were long, monotonous, and secret. The submarine would slip out into the North Atlantic and vanish beneath the waves for months. Only the crew, the Navy’s tracking stations, and a small circle of planners in Washington knew where she was.

The patrols followed a ritual pattern. The boat would head for its assigned patrol box, often in the stormy northern seas. There she would drift slowly or move in lazy ovals, maintaining communication only through coded messages sent in bursts. Life on board settled into routines of maintenance, drills, and quiet endurance. The crew knew that if their missiles were ever fired, civilization itself would be burning. That grim awareness shaped the culture of the early ballistic missile submarine force, a mixture of pride and fatalism.

In 1964 the Theodore Roosevelt completed her first overhaul and refit at Newport News Shipbuilding. The yard installed updated missile guidance systems and improved sonar gear. When she returned to sea, she was assigned to the Pacific, becoming the first ballistic missile submarine to make the trip from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the Panama Canal. She joined Submarine Squadron 15 at Guam, beginning deterrent patrols in the western Pacific. This redeployment reflected new strategic needs as the United States faced crises from Vietnam to the Taiwan Strait.

Theodore Roosevelt’s early years set the template for the next two decades. She performed more than thirty deterrent patrols through the 1960s, each lasting roughly seventy to eighty days. Crew rotations, constant drills, and tight discipline kept the complex machinery operating in the dark quiet of the deep. For her crew, she was a world unto herself, sealed off from the surface and from time.

In 1968, during operations off Scotland, the submarine reportedly grounded while maneuvering in fog near Holy Loch. The incident, though serious, caused no loss of life, and repairs were made. The grounding served as a reminder that even in peacetime the sea offered no forgiveness. Years later, crew members recalled the jolt, the alarms, and the eerie silence afterward as engineers checked the hull for leaks.

Theodore Roosevelt continued to operate through the 1970s, cycling between deterrent patrols and overhauls. Each refit brought technological upgrades. The once-cutting-edge Polaris A-1 was replaced by the longer-range Polaris A-3 missile, giving her the ability to strike targets from further offshore. Advances in sonar and navigation improved her stealth and accuracy. She remained a crucial node in the United States’ nuclear triad, part of the invisible guarantee that the Cold War stayed cold.

Her life, though secretive, intersected with history in subtle ways. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, she was on patrol, part of the unspoken threat that backed Kennedy’s blockade. During Vietnam, her presence in the Pacific symbolized the broader reach of U.S. power. When arms control negotiations began in the 1970s, boats like the Theodore Roosevelt were the very assets counted and limited in the SALT treaties. To her crew, these events filtered down as coded dispatches and whispers. To the world, her name rarely appeared in print.

By the early 1980s, newer submarines of the Ohio class had begun to replace the aging fleet. The Theodore Roosevelt, over twenty years old, still carried out patrols but was approaching the end of her operational life. She was deactivated on February 28, 1981, at Bangor, Washington. The process of defueling and dismantling a nuclear submarine was new and complicated. Her nuclear fuel was removed, her missile tubes disabled, and the hull prepared for storage. The Navy eventually towed her to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, where she entered the Nuclear-Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program.

Her final chapter played out far from the sea. In 1995, her reactor compartment, a massive steel cylinder, was transported by barge up the Columbia River to the Hanford Site in Washington State. There it was buried in Trench 94 alongside other submarine reactor sections. The rest of the hull was scrapped and recycled. It was a quiet end for a ship built for silent duty.

Yet the Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy did not fade. Her crews formed associations, sharing stories of long patrols and close calls. Veterans’ websites like Together We Served and HullNumber preserve rosters and photographs, small digital memorials to a vessel that once prowled the depths. The NavSource and NHHC archives contain striking images from her launch, christening, and operational life. In one, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the daughter of the ship’s namesake, swings the ceremonial bottle. In another, she sits proudly alongside sailors in starched whites, a living link between the Rough Rider and the nuclear age.

For naval historians, the Theodore Roosevelt marks a transition in submarine design and doctrine. She was part of the Ethan Allen class, the first group built from the keel up as missile boats rather than converted attack submarines. Her design set the pattern for subsequent classes, including the Lafayette, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin boats. Each of these refined the balance between speed, stealth, and missile capacity. The Theodore Roosevelt’s twin crews and relentless patrol cycle helped refine the “two-crew concept” that became standard practice for ballistic missile submarines, allowing continuous deterrent coverage.

The human side of her story carries its own weight. Men lived for months in a steel tube barely wider than a city street, trusting in each other and in machinery they could not always see. They missed births, holidays, and seasons. Letters came by pouch to the tender at Holy Loch or Guam, then filtered down through coded channels. When they surfaced at the end of a patrol, the first lungful of sea air felt like another world. Those who served on her speak of discipline, pride, and an odd affection for the claustrophobic hum of the reactor.

To the broader public, she remained largely invisible. Her patrols were secret, her missions unheralded. Yet her existence shaped the strategic landscape of the late twentieth century. Every adversary that calculated the risks of nuclear war had to account for the boats like hers that might be lurking somewhere, undetected and ready. That uncertainty was her weapon.

Looking back, the USS Theodore Roosevelt’s story is both triumph and irony. She carried the most destructive weapons ever built, yet her success lay in never firing them. She represented a blend of technological mastery and moral burden, the belief that peace could be maintained by the promise of annihilation. For a ship named after a man who preached the virtues of the “big stick,” it was a fitting if somber legacy.

Today, fragments of her remain in museums and private collections: a plaque here, a crew patch there, perhaps a piece of deck plate salvaged before scrapping. Her reactor compartment lies entombed in the desert, a relic of the age of deterrence. The rest exists in memory, in faded cruise books, and in the quiet pride of those who served aboard.

Theodore Roosevelt once said that a man should “do what you can, with what you have, where you are.” The submarine that bore his name lived that creed beneath the waves. She stood her silent watch through decades of tension, ready but never called. In that restraint lies her real achievement. She was built for war but served for peace, a reminder that sometimes the greatest acts of courage are the ones no one ever sees.

Citations

- Naval History and Heritage Command. “Theodore Roosevelt II (SSBN-600).” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/t/theodore-roosevelt-ii.html

- “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600).” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Theodore_Roosevelt_%28SSBN-600%29

- NavSource Online. “Submarine Photo Index: USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600).” https://www.navsource.net/archives/08/08600.htm

- NavSource Online. “History of USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600)” [PDF]. https://www.navsource.net/archives/08/pdf/0860080.pdf

- Naval History and Heritage Command. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600),” photograph USN-1053537. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/USN-1053000/USN-1053537.html

- Together We Served. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600) Unit History.” https://navy.togetherweserved.com/usn/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?ID=604&cmd=UnitHistoryDetail&type=UnitHistory

- NavySite.de. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600).” https://www.navysite.de/ssbn/ssbn600.htm

- NavySite.de. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600) Crew List.” https://www.navysite.de/crewlist/commandlist.php?commandid=898

- HullNumber.com. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600) Crew Roster.” https://www.hullnumber.com/crew1.php?cm=ssbn-600

- Mesothelioma.net. “USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600) and Asbestos Exposure.” https://mesothelioma.net/uss-theodore-roosevelt-ssbn-600-and-asbestos/

Leave a comment