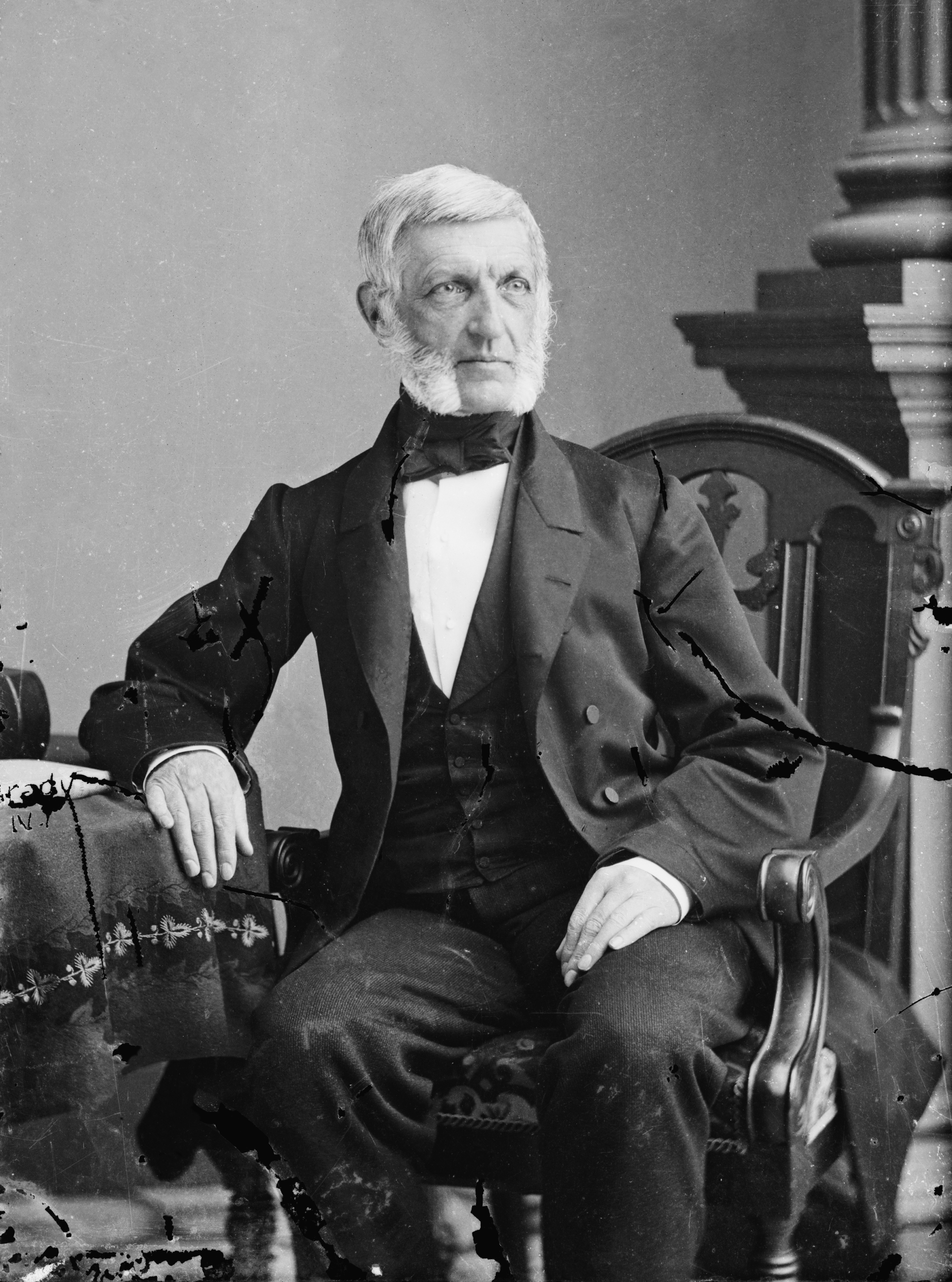

George Bancroft’s life was a blend of scholarship, politics, and vision. Born on October 3, 1800 in Worcester, Massachusetts, he became one of the most significant American historians of the nineteenth century. His multivolume History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent established him as the voice of America’s past. Yet his greatest contribution to the Navy came during his brief time as Secretary of the Navy under President James K. Polk. In 1845 he used the authority of his office to establish the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, creating a permanent institution where midshipmen would be educated and trained before serving at sea. Bancroft’s clever maneuvering allowed him to build the school first and secure congressional approval later, ensuring the Academy became a lasting part of the Navy’s future.

More than a century after Bancroft’s service, the Navy honored him by naming a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine in his memory. USS George Bancroft (SSBN-643) was commissioned in 1966 as part of the “41 for Freedom,” a fleet of ballistic missile submarines that formed the backbone of America’s Cold War deterrent. She carried missiles that evolved from Polaris to Poseidon to Trident, each stage reflecting the technological race of the era. From her first patrol in 1966 until her decommissioning in 1993, she served silently beneath the seas, prepared to strike if deterrence failed. In both the man and the vessel, the Navy recognized a shared legacy of strength: Bancroft through his creation of an enduring institution, and the submarine through her role in safeguarding peace during a perilous century.

George Bancroft was born on October 3, 1800, in Worcester, Massachusetts, into a family deeply tied to the nation’s early history. His father, Aaron Bancroft, had fought in the Revolutionary War and later became a respected Unitarian minister. The younger Bancroft inherited both a love of learning and a sense of duty to the republic.

From an early age he demonstrated extraordinary intellect. He studied at Phillips Exeter Academy before entering Harvard College at thirteen, graduating in 1817 at the age of seventeen. Seeking a broader education, he continued his studies in Germany, attending the universities of Göttingen and Berlin. At Göttingen he earned a doctorate in 1820, one of the few Americans of his generation to achieve that distinction. These years abroad shaped his belief that disciplined institutions and rigorous scholarship could strengthen a nation’s character and leadership.

Bancroft returned home determined to write the story of his country. His History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent became the definitive national chronicle of the era. He portrayed America’s rise as both providential and inevitable, weaving liberty and republican values into a grand narrative. His work offered Americans pride in their past and confidence in their destiny.

Public life soon followed. He served as Collector of the Port of Boston, where he appointed Nathaniel Hawthorne to a customs post. In 1845 President James K. Polk appointed him Secretary of the Navy. Though he held the office for only a year, his impact was immense. Bancroft founded the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, using his authority to house midshipmen and assign instructors at Fort Severn before Congress could object. By the time lawmakers addressed the matter, the Academy was already operating, and it has endured ever since as his most lasting gift to the Navy.

Bancroft’s career extended further. He served as U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1849, then later represented the United States in Prussia and the German Empire between 1867 and 1874. His negotiations produced the Bancroft Treaties, which secured recognition of the American principle of expatriation and protected the rights of naturalized citizens abroad. In these roles, he blended the historian’s eye for the sweep of events with the diplomat’s skill in shaping them. By the time of his death in 1891, Bancroft was remembered as both the historian of the American nation and one of the architects of its modern Navy.

The submarine that bore George Bancroft’s name was born out of the Cold War’s most urgent demand: to ensure that the United States could strike back if ever attacked with nuclear weapons. On November 1, 1962, the Navy awarded a contract to General Dynamics’ Electric Boat Division in Groton, Connecticut, for the construction of a new ballistic missile submarine. She would be one of the Benjamin Franklin-class boats, part of the “41 for Freedom,” a fleet designed to keep America’s nuclear deterrent hidden beneath the seas.

Her keel was laid on August 24, 1963. Over the next two years the submarine took shape, 425 feet of steel stretching across the Groton shipyard. She displaced more than 8,250 tons submerged, driven by a nuclear reactor that allowed her to stay underwater for months at a time. Sixteen vertical missile tubes stood at her core, capable of launching Polaris ballistic missiles, and she carried four forward torpedo tubes for defense. This was the Navy’s answer to the Soviet threat: a ship that could not be found, could not be preempted, and could hold entire cities at risk if war came.

On March 20, 1965, she slid down the ways into the Thames River. The ceremony was sponsored by Bancroft’s descendants, Mrs. Jean B. Langdon and Mrs. Anita C. Irvine, who christened the vessel with the traditional bottles of champagne. It was a moment that linked the nineteenth-century statesman who had founded the Naval Academy to the nuclear age weapon that now carried his name.

USS George Bancroft SSBN-643 was commissioned on January 22, 1966. Two crews were established to maximize her patrol time: Captain Joseph Williams commanded the Blue Crew and Commander Walter M. Douglas commanded the Gold. Their mission was clear. They would take their turns leading the ship into the deep ocean, vanish from the surface world, and wait in silence. The submarine was not designed for glory or headlines. She was designed to deter, to remind any adversary that an attack on the United States would guarantee devastating retaliation.

Her first deterrent patrol began on July 26, 1966, from New London, Connecticut, and ended at Holy Loch, Scotland. It set the pattern for the decades to come. Between 1966 and 1993, USS George Bancroft completed seventy deterrent patrols. She shifted missile systems as technology advanced, moving from Polaris to Poseidon and finally to Trident C-4. Each upgrade extended her reach and kept pace with the evolving threat.

Life aboard was demanding. Crews lived in close quarters for months at a time, cut off from family and the world above, maintaining constant readiness. The Navy rewarded their dedication. The boat earned Meritorious Unit Commendations in 1971 and 1984, multiple Battle Efficiency Awards in 1980, 1984, 1985, and 1991, and was named Atlantic Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarine of the Year in 1984. Between patrols she underwent overhauls and refueling, most notably from 1986 to 1988, ensuring she remained a credible part of the deterrent force until the end of her career.

By the early 1990s the Cold War was winding down, and the newer Ohio-class submarines had taken over the primary deterrent mission. On March 1, 1993, George Bancroft surfaced for the last time using an emergency blow test. Later that year, on September 21, she was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. In 1998 she was recycled through the Nuclear-Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program in Bremerton, Washington.

Her story did not end there. The submarine’s sail was preserved and placed on display at Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia. Dedicated on April 7, 2000, the exhibit was designed to appear as though George Bancroft was emerging once more from the depths. It stands today as a memorial to the boat and to the men who served aboard her, a permanent reminder that peace during the Cold War was secured not only by treaties and speeches, but by submarines like this one quietly carrying out their patrols beneath the sea.

George Bancroft’s influence is etched into the life of the Navy and the nation. At the United States Naval Academy, his vision lives on in Bancroft Hall, the world’s largest single dormitory. Known simply as “Mother B,” it houses thousands of midshipmen who pass through its halls on their journey to becoming naval officers. Every formation, every return from the drill fields, and every late-night study session takes place under the roof of the building named for the man who founded the Academy. For more than a century, it has served as both a monument and a daily reminder of the power of institutions to shape leaders.

The legacy of USS George Bancroft is preserved in a different way. After her decommissioning in 1993 and recycling in 1998, her sail was saved as a tribute. At Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay in Georgia, the sail rises from a grassy field at the Franklin Gate, giving the impression that the submarine is surfacing one final time. Dedicated on April 7, 2000, during the centennial celebration of the U.S. Navy’s Submarine Force, the monument honors both the boat and the generations of submariners who served in silence beneath the sea. Families, veterans, and visitors who pass through the gate are greeted by the symbol of a ship that once roamed the oceans unseen, part of the hidden shield that protected the nation during the Cold War.

Together, the man and the submarine that bore his name embody the Navy’s dual heritage of vision and vigilance. Bancroft gave the Navy its Academy, ensuring that officers would be trained in a professional institution dedicated to excellence. The submarine carried that legacy forward into the nuclear age, where the quiet endurance of her patrols kept peace during decades of tension. From the granite walls of Bancroft Hall to the black steel sail at Kings Bay, both remind us that service takes many forms. One was a statesman and historian, the other a machine and a crew of determined sailors. Both were dedicated to national security and the preservation of freedom, and both continue to speak to the enduring strength of the United States Navy.

Leave a comment