San Pedro Harbor, late September 1921. The Pacific Fleet’s new base was a place alive with the restless energy of a Navy in transition. Battleships and destroyers filled the anchorage, while a cluster of small, dark-hulled submarines rocked gently in their moorings beside the big tender USS Camden. The sun had set, but the harbor was far from quiet. Ashore, the city of Los Angeles was swelling into one of the nation’s fastest growing metropolises, and the Navy’s presence was both a symbol of American reach and a reminder of unfinished business after the First World War. For the sailors aboard USS R-6, the night of September 26 began as another routine round of preparations for training exercises. Within hours, however, it would end with their boat lying on the harbor bottom and two of their shipmates dead.

The R-6 was a product of the so-called pigboat era of American submarine development. These were not yet the ocean-ranging predators of World War II fame, but compact coastal-defense craft built to operate close to home waters. They were experimental in many ways, bridging the crude designs of the early 1900s and the more capable fleet submarines that would follow. They were also inherently dangerous. Mechanical systems were temperamental, interlocks and safety devices were primitive, and every evolution carried risks. Crews understood that even in peacetime, the sea was unforgiving, and a minor failure could mean catastrophe.

The events of that September night made those risks painfully clear. While preparing practice torpedoes for battle drills scheduled the next day, the crew of R-6 suffered a malfunction that allowed seawater to surge into the forward torpedo room. What began as a technical glitch spiraled into chaos as compartments flooded, hatches slammed shut, and sailors fought to escape. Some scrambled out through deck hatches, others rushed to secure systems, and at least one man hacked through the submarine’s mooring lines to prevent the sinking R-6 from pulling down her neighbors. Within minutes, the boat was gone, settled upright in thirty-five feet of water, her bow buried in the harbor mud.

The sinking was not the Navy’s first submarine accident, nor would it be the last. It claimed two men, Electrician’s Mate Second Class Frank Amzi Spalsbury and Seaman John Edward Dreffein, whose stories remain part of submarine memorial rolls. Yet it was also a case study in resilience. The Navy salvaged R-6 less than three weeks later, restored her to service, and gave her a career that stretched across two decades and two world wars. In the process, the boat became a symbol of both the hazards and the adaptability of the early submarine force.

The sinking of R-6 on September 26, 1921, was a tragedy, but it was also a moment that captured the essence of the pigboat era: the blend of innovation, risk, loss, and perseverance that defined the birth of the American undersea fleet. This is her story.

“To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives

USSVI Creed

in pursuit of their duties while serving their country.

That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice

be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments.”

To understand the fate of R-6, it is necessary to step back into the world of the pigboats. The word itself was not affectionate. Sailors of the era compared their submarines to iron coffins, but the pigboat moniker captured something else — their squat, rounded hulls, the foul smells of diesel and oil, the squeals and groans of pipes under pressure, and the simple fact that they were small, dirty, and often temperamental. Yet in these primitive vessels, the U.S. Navy laid the foundations of the submarine force that would eventually strangle the Japanese Empire in the Second World War.

The R-class was conceived in the final stretch of World War I, when American strategists realized that submarines were no longer experimental toys but essential tools of naval warfare. The German U-boat campaign in the Atlantic had proven how devastating undersea craft could be, and the United States scrambled to expand its own force. Unlike the larger S-boats and fleet submarine prototypes being considered, the R-class was intended to be a coastal-defense workhorse. They were meant to patrol harbors, protect shipping lanes near home, and train crews for the larger boats that lay ahead.

The Navy ordered twenty-seven R-class submarines, but in typical Navy fashion, they were split between two builders. Electric Boat Company of Groton, Connecticut, designed and constructed R-1 through R-20, while the Lake Torpedo Boat Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut, received the contract for R-21 through R-27. On paper, they were supposed to be interchangeable. In practice, they were cousins rather than twins. Lake boats were heavier and slightly slower, while Electric Boat’s hulls carried forward the basic single-hull construction of the earlier O-class, only on a slightly larger frame.

For their time, the Electric Boat R-boats were advanced. They were the first American submarines fitted with 21-inch torpedo tubes, a caliber that quickly became the world standard. Unlike earlier designs that used rotating bow caps to cover multiple tubes, the R-class had individual muzzle doors. It was a step forward in reliability, but as the R-6 would later demonstrate, it was not foolproof. The boats carried four tubes forward, no stern tubes, and a 3-inch/50-caliber deck gun that was fixed rather than retractable. That gun gave the R-boats a punch against small surface craft or unarmed merchants, although in practice they were rarely used in combat.

Their performance was modest but respectable. At 186 feet long with a beam just under 20 feet, they displaced 569 tons on the surface and 680 submerged. A pair of diesel engines powered them at 13.5 knots on the surface, while electric motors gave them a submerged speed of about 10.5 knots. Their endurance was limited — coastal patrols rather than transoceanic voyages — and their complement was 34 officers and men. By later standards this was cramped and spartan, but for crews of the 1920s it was simply life in the boats.

The R-class embodied the contradictions of the pigboat era. They were technological advances over the O-class, introducing features that would become standard, yet they remained vulnerable to the smallest failures. They were designed to prepare the Navy for future wars, but they carried crews who lived with the daily reality that their lives might end in peacetime training accidents. USS R-6 was one of these boats, a representative of both progress and peril, and her story would prove just how fine that line could be.

USS R-6 entered the water on March 1, 1919, sliding down the ways of Fore River Shipbuilding Company in Quincy, Massachusetts. The war for which she had been built was already over, but the Navy was not about to discard new submarines. The United States had emerged from the First World War with ambitions for a modern fleet, and every vessel that had been laid down was still needed to project power, train sailors, and flesh out the undersea force. When R-6 was commissioned at Boston on May 1, 1919, she joined that push, one small but important cog in a growing machine.

Her first assignment was to Submarine Division 9 of the Atlantic Fleet, based at New London, Connecticut. New London was the heart of the Navy’s submarine activity on the East Coast, and for a boat like R-6, the work was as much about training as it was about operations. Crews learned the quirks of the new 21-inch torpedo tubes, drilled in emergency procedures, and endured the cramped, oil-soaked environment of life aboard. The sailors who served in her were young, often first-time submariners, gaining experience in a service that was still defining itself.

In January 1920, R-6 headed south with her division for winter maneuvers in the Gulf of Mexico. Submarines of this era were not especially seaworthy in rough waters, and the Gulf offered both a relatively mild climate and a proving ground for coordination with the surface fleet. These exercises were about more than practice attacks. They tested the endurance of machinery, refined communication with destroyer escorts, and helped commanders understand the role submarines might play in coastal defense. By April she was back at New London, and that summer her division carried out additional training before R-6 went in for an overhaul at Norfolk.

During this period, the Navy began reorganizing its fleet to match postwar priorities. In July 1920, the hull classification system was formally adopted, and R-6 received her permanent designation as SS-83. That small change reflected a larger shift. The United States was codifying its submarine force, turning a hodgepodge of designs into a structured fleet with clear categories.

The biggest change for R-6 came in 1921. On April 11 she was ordered to shift to the Pacific Fleet, a sign of how rapidly the Navy was consolidating its strength on the West Coast. The opening of the Panama Canal had made transfers between oceans far more practical, and R-6, along with other boats of her division, steamed south and passed through the Canal on May 28. The voyage itself was an adventure. Early submarines had limited range and comfort, and their crews spent much of the trip either surfaced in tropical heat or struggling with the stifling atmosphere of submerged runs.

By June 30, 1921, R-6 arrived in San Pedro, California. Los Angeles was booming, and San Pedro had only recently been designated the new home of the Battle Fleet. Battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and tenders crowded the harbor, and the R-class submarines were now part of a Pacific base that was becoming central to American naval strategy. For the men of R-6, the move was a chance to prove themselves in new waters, to hone skills under the eyes of senior commanders, and to prepare for the constant rhythm of training that defined peacetime service. None of them could have known that within three months, their submarine would lie on the bottom of that very harbor.

September 26, 1921 began like any other day in San Pedro. The battleships of the Pacific Fleet swung lazily at anchor, destroyers bustled in and out of the harbor, and the small, unglamorous R-class submarines kept to their routine. For the crew of USS R-6, moored in a nest of boats tied to the tender USS Camden, it was supposed to be a straightforward night of preparations. Battle practice had been scheduled for the following day, and the torpedo gang was tasked with readying the exercise fish. The sun had dipped below the horizon, and lanterns glowed inside the forward torpedo room as sailors fitted dummy warheads and checked the new 21-inch tubes. Nothing suggested disaster was only moments away.

The R-6’s torpedo system, like those of her sisters, relied on a safety device known as an interlock. Its purpose was simple but vital: to make it impossible for both the inner breech door and the outer muzzle door of a torpedo tube to be open at the same time. If both doors were open, the sea had a direct path into the submarine, and flooding was inevitable. On paper, the system was foolproof. In practice, it was only as reliable as its weakest component.

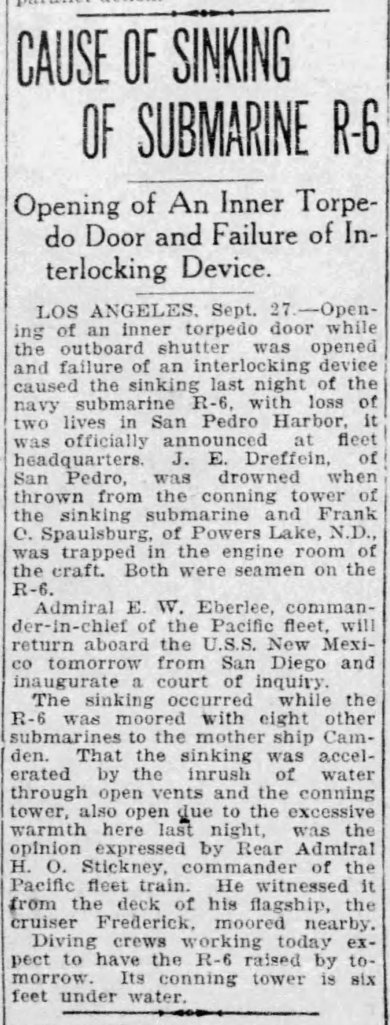

That night, the interlock failed. Accounts differ on whether the muzzle door had been left slightly open or whether the mechanism slipped, but when the crew swung open a breech, the sea came roaring in. Water poured into the forward torpedo room, overwhelming sailors who only seconds before had been focused on the mechanical routine of their work. Within heartbeats the compartment was awash, lights flickered, and the shrill cry of alarms spread through the submarine.

The forward crew fought to save themselves. Some clawed their way up to the deck hatch, pushing into the night air as the bow of R-6 settled. Others rushed aft, slamming shut watertight doors in a desperate attempt to contain the flooding.

Amid the chaos, one act of quick thinking prevented a larger disaster. As the R-6 began to drag downward, she threatened to pull the other submarines in the nest down with her. A crewman hacked through the mooring lines, freeing the neighboring boats and sparing the Navy from losing not just one but several submarines in the span of minutes. It was an act of desperation and heroism rolled into one.

The R-6 gave no further reprieve. With her bow flooding unchecked, she slipped beneath the surface and settled upright on the bottom, only thirty-five feet below. To onlookers on the tender and the other submarines, the scene was surreal. One moment she was there, her hatches open and crew scrambling across her deck. The next she was gone, bubbles marking the spot where she had vanished into the harbor mud.

For a time, there was hope that men might have survived in sealed compartments. Divers were summoned, and through the night they tapped on the hull, straining to hear an answering knock. None came. The sinking had been too sudden, the flooding too swift. When dawn broke over San Pedro on September 27, the outline of R-6 could just be made out beneath the clear waters, her slender hull lying motionless on the bottom. For the Navy, the immediate questions were grimly familiar: how many men had been lost, what had caused the failure, and how could the submarine be brought back up. For the families of the crew, there was only the terrible wait for news.

When R-6 disappeared beneath the surface of San Pedro Harbor, the majority of her crew managed to escape. They clambered through hatches or swam to safety, pulled aboard neighboring boats or the tender Camden. But two men did not come back. Their names joined the solemn roll of submariners lost in accidents, men who never went to war but paid the same price as those who did.

The first was Electrician’s Mate Second Class Frank Amzi Spalsbury. Born in 1898 in the small farming town of Powers Lake, North Dakota, he had grown up in a place where the horizons seemed endless and the Navy must have felt like another world entirely. He enlisted young, drawn into the service in the years after the First World War, and found himself in the submarine force, one of the most demanding assignments in the fleet. On the night of September 26 he was in the conning tower, trying to reach safety as the bow flooded. When seawater rushed into the forward battery it caused a short and a small explosion that blew him out through the hatch. For three days his body lay on the harbor bottom, only ten feet from the hull of his submarine. Divers recovered him on September 29. He was returned home and buried in Powers Lake, mourned by a family and community who had watched him leave for service and never expected the sea would claim him.

The second man was Seaman John Edward Dreffein. He came from the town of Three Oaks in southwest Michigan, a community of orchards, farms, and small industry. Born in 1901, Dreffein had enlisted in the Navy as a teenager, part of a generation of young men eager to see the world beyond their rural roots. Service aboard a submarine was no easy posting, but like many sailors he embraced the challenge and the camaraderie of the tight-knit crews. On the night of the accident, Dreffein was trapped inside the submarine when she went down. For weeks his fate was uncertain. Divers tapped on the hull, listening for signs of life, and some ashore believed he might have found an air pocket. But no answer ever came. When R-6 was finally raised on October 13 and opened, Dreffein’s body was found inside. He was laid to rest in Rock Island National Cemetery in Illinois, far from San Pedro but among fellow servicemen.

In the hours after the sinking, the Navy threw itself into the work of rescue and salvage. Divers descended into the harbor before dawn, hammering on the hull in hopes of hearing trapped men respond. None did. A floating crane was brought in to lift the boat, but it could not overcome the weight of the flooded hull. Pumps failed to make progress. For more than two weeks, the submarine lay on the bottom in plain sight of the fleet.

At last, on October 13, the minesweeper USS Cardinal and the sister submarine USS R-10 managed to raise her. The Cardinal supplied lifting gear while R-10 forced high-pressure air into the hull, expelling water and restoring buoyancy. Slowly, R-6 broke the surface again. She was battered but intact, her two lost sailors still aboard. Their recovery gave closure to their families, and the return of the submarine gave the Navy a chance to learn from the accident and to restore a valuable vessel.

The loss of Spalsbury and Dreffein was not forgotten. Their names appear on memorial rolls that honor submariners lost in peacetime and war alike. They represented the human cost of the early submarine service, young men from small American towns who found themselves in the unforgiving world of undersea warfare. R-6 would sail again, but for their families, the night of September 26, 1921, would remain an indelible tragedy.

For most submarines, a sinking meant the end. Yet for R-6, September 26, 1921 was not a full stop but a harsh pause. The Navy had invested heavily in its young undersea fleet, and there was no appetite to discard a relatively new boat. Once she was raised and repaired, R-6 was restored to duty. Her scars from San Pedro were patched over, and by the early 1920s she was again at sea, carrying a crew that knew her past and understood her hazards.

Her first assignment after repairs was unlike anything most submariners could have imagined. In February 1923, Hollywood came calling. Twentieth Century-Fox was filming The Eleventh Hour, a silent-era drama that required authentic submarine footage. R-6 was loaned to the studio from February 26 to March 2, and her compact hull, cramped interiors, and surfacing maneuvers all made it to the silver screen. For a brief moment she was not just a Navy pigboat but a movie star, preserved in flickering images that reached audiences across the country.

Not long after her brush with fame, R-6 was sent to Hawaii, where she would spend the better part of eight years. Arriving at Pearl Harbor in July 1923, she joined a flotilla of submarines used for training and fleet exercises in the central Pacific. The Hawaiian station was still relatively undeveloped compared to the grand base it would become in 1941, but the Navy recognized its importance as an outpost for projecting American power into the Pacific. For the crews of the R-boats, duty there meant long days of drills under the tropical sun, torpedo exercises, and coordination with surface forces. R-6’s years in Hawaii were routine but valuable, building a generation of submariners who would later serve in the larger, more capable fleet boats of World War II.

By 1931, however, the R-class boats were showing their age. They were cramped, underpowered, and limited in range. On February 9, R-6 returned to Philadelphia, and by May 4 she was decommissioned. Many assumed that would be the end of her story. She was tied up in reserve, one of dozens of pigboats that seemed destined for scrap.

History had other plans. With war looming in Europe, the Navy reevaluated every available hull. On November 15, 1940, R-6 was recommissioned at New London. She was old, but she was still useful. At first she was sent to the Caribbean for patrol duties, guarding against German U-boats that prowled increasingly close to American shores. Later she was stationed along the line between Nantucket and Bermuda, a barrier patrol designed to detect and deter enemy submarines. She was no longer a cutting-edge warship, but she served as a deterrent, an extra set of eyes and ears in waters that were growing more dangerous by the month.

Her long service was not without incident. On March 13, 1943, R-6 was conducting exercises off Block Island, Rhode Island, when American torpedo bombers mistook her for a German U-boat. They dropped depth charges and made runs at the little submarine before the mistake was realized. R-6 survived without damage, but the incident underscored the perils of operating in wartime waters, where friend and foe could be difficult to distinguish.

From 1943 onward, her role shifted primarily to training. Destroyers and destroyer escorts needed experience in antisubmarine warfare, and the old pigboats provided perfect live targets. R-6 spent countless hours submerged and surfaced while surface crews practiced detection, tracking, and simulated attacks. For her weary hull and her patient crew, it was repetitive work, but it prepared younger sailors for the deadly cat-and-mouse duels that raged across the Atlantic.

In 1945, as the war neared its end, R-6 took on one final, unexpected assignment. The Navy had begun experimenting with a device that would revolutionize submarine warfare: the snorkel. Borrowed from the Germans and refined by American engineers, it allowed a submarine to run its diesel engines while submerged, vastly increasing endurance and reducing vulnerability. Between April and August 1945, R-6 served as the test platform for the Navy’s first snorkel trials off Fort Lauderdale, Florida. For a boat that had once sunk ignominiously at her moorings, it was an extraordinary finale, helping to pave the way for the next generation of submarines.

Her long journey ended quietly. On September 27, 1945, just weeks after the surrender of Japan, R-6 was decommissioned at Key West. She was struck from the Navy list on October 11 and sold for scrap in March 1946. Few outside the submarine force noticed her passing.

Yet her career had been remarkable. Raised from the harbor mud in 1921, she had gone on to serve in Hollywood, in Hawaii, in Caribbean patrols, in Atlantic training, and even in experimental work that shaped the postwar fleet. She had outlived many of her sisters, and she had served across two world wars. For a boat dismissed as a pigboat, R-6 had left a legacy of endurance.

The sinking of USS R-6 on September 26, 1921, was a moment born from the vulnerabilities of early submarine technology. A failed interlock, a rush of seawater, and within minutes a boat was on the harbor bottom. It could have ended there, another tragic accident written into the long list of losses that marked the pigboat era. Instead, R-6 was raised, repaired, and returned to service. Her career, stretching across two decades and two world wars, proved that even a scarred vessel could still serve with distinction.

Her story embodies the contradictions of her age. She was both fragile and durable, outdated almost from the start yet capable of extraordinary endurance. She trained crews, patrolled against U-boats, and even helped usher in new technology with the first snorkel trials. From San Pedro to Hawaii, from Hollywood to Fort Lauderdale, she left her mark in ways her builders never expected.

But the true measure of her legacy lies not only in the steel that was raised from the mud, but in the lives that were lost when she went down. Electrician’s Mate Second Class Frank Amzi Spalsbury of Powers Lake, North Dakota, and Seaman John Edward Dreffein of Three Oaks, Michigan, were young men who answered their country’s call. They did not die in combat, but in service, and their sacrifice stands equal with any who never returned from patrol. As the creed of the United States Submarine Veterans reminds us, their names must be perpetuated, their deeds remembered, and their supreme sacrifice honored as a source of motivation for all who wear the dolphins.

R-6 is gone now, struck from the Navy list in 1945 and broken up for scrap the following year. Yet her story lives on in the chronicles of the submarine force and in the memory of those who honor the pathfinders of the deep. To tell her story is to keep faith with the men who sailed her, and especially with those who did not come back. That is the enduring duty of the submarine community, and it is why, more than a century later, we still say their names: Frank Amzi Spalsbury and John Edward Dreffein.

Leave a comment