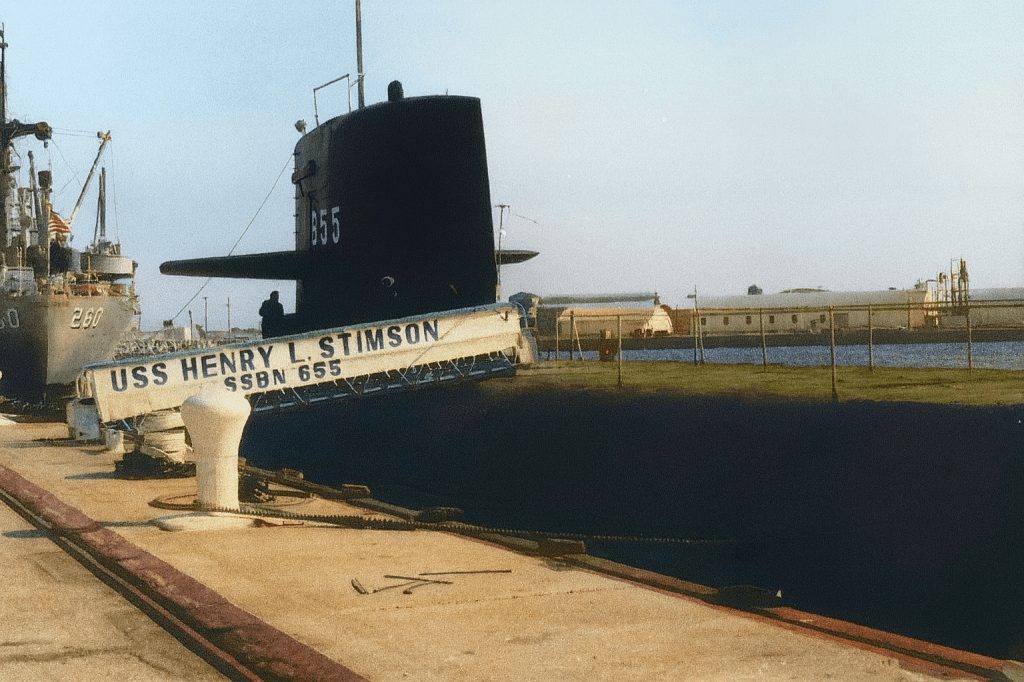

There are ships that fight in battles, their names carved into the bright lights of history, remembered for decisive cannon fire or desperate torpedo runs. And then there are ships whose purpose was never to fight at all, but to disappear into the world’s oceans, waiting in silence with the power to end civilization. The USS Henry L. Stimson (SSBN-655) belonged to that second group. She was one of the “41 for Freedom,” America’s fleet of nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines that patrolled the oceans through the Cold War, holding the line by being invisible. Her story is not one of thundering combat but of quiet endurance, of young men living under the sea for months at a time, and of the statesman whose name she bore, a man who wrestled with the morality of nuclear weapons before most of her crew were even born.

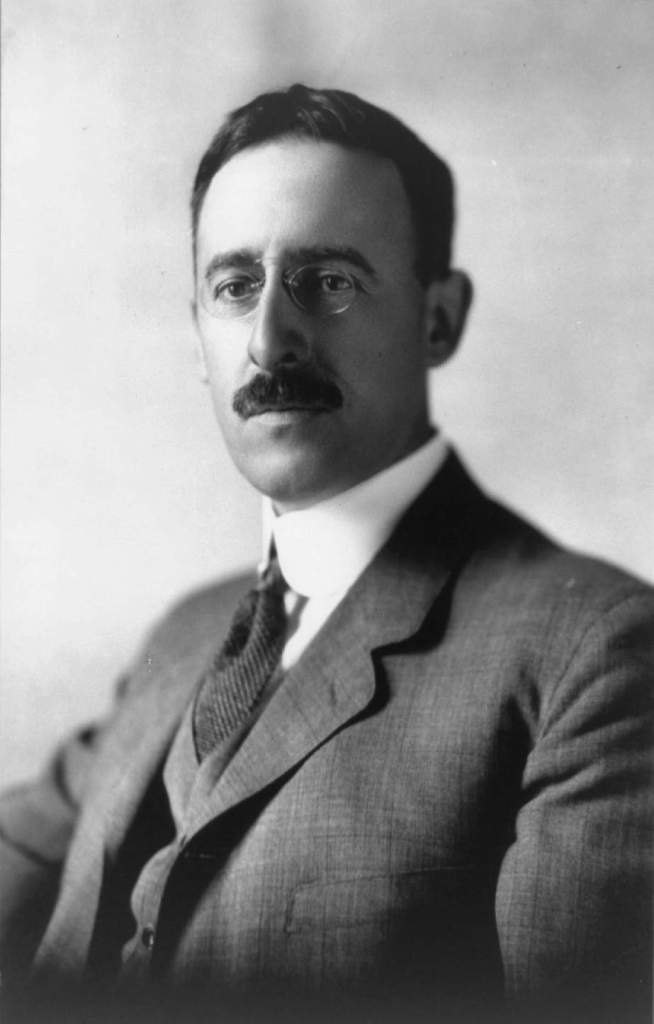

Henry Lewis Stimson was born on September 21, 1867, in New York City. He came from a privileged family but was shaped by a stern sense of duty. He went to Yale, where he joined Skull and Bones, that strange incubator of future leaders, and later studied at Harvard Law School. He made his name as a lawyer in New York, arguing cases with the confidence of a man who believed in order and discipline. Politics pulled him in soon after. By 1911 he was Secretary of War under William Howard Taft, a Republican lawyer asked to manage an army still tiny by world standards. In 1929, Herbert Hoover made him Secretary of State. He presided over the early years of the Great Depression and watched the world tilt toward crisis. Then, in 1940, Franklin Roosevelt reached across party lines and asked the aging Stimson, now in his seventies, to return to the War Department. He accepted. It would be his most defining role.

As Secretary of War during World War II, Stimson oversaw the largest mobilization in American history. He managed the raising of divisions, the building of tanks, the turning of factories into arsenals. Yet one project consumed him more than any other. It was called the Manhattan Project. Stimson knew that unleashing atomic power would change not just the war but human history itself. He authorized funds, oversaw security, and in the summer of 1945 advised President Truman on the use of the bomb. Famously, he warned against targeting Kyoto, arguing that the ancient capital carried too much cultural value to be sacrificed. He was a man who combined hard calculation with an old-fashioned sense of morality. When he died in 1950, his career spanned two world wars and the dawn of the nuclear age. To name a ballistic missile submarine after him was fitting, almost poetic. His life story was about the management of war and the hope of peace through strength. His namesake submarine carried that same paradox into the depths of the Atlantic.

The submarine that bore his name was laid down at the Electric Boat yard in Groton, Connecticut on April 4, 1964. She was part of the Benjamin Franklin-class, the last refinement of the original fleet of nuclear missile boats. These ships were quieter than their predecessors, better designed for long patrols, and dedicated solely to the mission of deterrence. The Stimson slid down the ways on November 13, 1965, and was formally commissioned on August 20, 1966. From the start she had two full crews, Blue and Gold, a system invented to maximize patrols while still giving sailors time with their families. Each crew trained while the other patrolled. When the boat returned, they swapped. It was a rhythm that allowed these submarines to remain on station almost continuously.

Her first deterrent patrol began on February 23, 1967, sailing from Charleston with sixteen Polaris A-3 missiles in her launch tubes. It was a routine that would become second nature: slip the mooring lines, vanish beneath the surface, and head into a patrol box somewhere in the Atlantic. To the families left behind there was silence. Letters might reach the boat through carefully controlled channels, but the men on board could not speak of where they were or what they were doing. One sailor remembered years later, “We were ghosts with missiles. Our wives never knew where we were, and the Soviets could only guess.” For all the secrecy, there was pride in the mission. The crew knew that by being undetectable, they were preventing war. Deterrence was measured not in battles won but in battles avoided.

Life on board was claustrophobic and relentless. Fresh food disappeared in the first weeks, replaced by frozen and canned stores. The air was recycled, the atmosphere scrubbed by chemical canisters. The smell of machinery and hydraulic oil became as familiar as the beating of one’s own heart. The days blurred. There were no sunrises or sunsets, only the steady routine of watch rotations and drills. A mess attendant recalled that the only way to mark the passage of time was by the changing menu. “When we got down to powdered milk, you knew you were halfway through.” Yet there were lighter moments too. Movies were swapped, card games played, and sailors invented traditions to break the monotony. The crew became a family, bound by necessity in the steel confines of their boat.

By 1970 the Stimson had settled into the rhythm of deterrent patrols. In August of that year she was awarded a Meritorious Unit Commendation, a sign that her performance had stood out even in a fleet that prized reliability. The details remain classified, but veterans suggest it had to do with readiness and the seamless execution of her mission. In November 1971 she entered Newport News Shipyard for her first major overhaul. This was not just maintenance. She was being converted to carry the new Poseidon C-3 missile. Poseidon doubled the number of warheads, improved accuracy, and represented the next generation of nuclear firepower. For the crew it meant retraining, new systems, and more complexity. In 1973, after months of work, both crews took her to sea for Demonstration and Shakedown Operations. The sight of a missile leaving its tube in a white plume of spray was awe-inspiring. For most submariners, these DASO launches were the only time they ever saw the weapons fired. They proved the system worked and then went back to silence.

From 1973 until 1979 the Stimson conducted twenty-four Poseidon deterrent patrols out of Rota, Spain. Squadron 16 kept a constant rotation there, American submarines slipping in and out while Soviet intelligence trawlers lurked offshore. Rota became a second home for many of the crews. They would fly in, relieve the other crew, and take the boat to sea for three months. The men remembered the peculiar experience of beginning a patrol in Europe, spending months submerged, and then stepping off the boat to find themselves in Spain again, as if time itself had stood still. Life aboard had its rhythms. Drills, training, and maintenance filled every day. Sailors marked their bunks with small tokens, photographs of sweethearts, or football pennants from home. One man recalled that the most beautiful sight of a patrol was not the ocean itself but the tray of fresh fruit waiting on the pier when they finally returned. In November 1976 the Blue Crew conducted an Operational Test launch of two Poseidon missiles, a rare live firing that reassured both the Navy and the nation that the system remained credible.

By the end of the 1970s the Navy was preparing to deploy the new Trident system. Rather than build an entirely new fleet from scratch, some boats were chosen to be backfitted with the Trident I (C-4) missile. The Stimson was one of them. In late 1979 she entered Charleston for the conversion. It was a pierside job, less disruptive than a full yard overhaul but still intense. By February 1980 she was ready. In May she began her first patrol with Trident. The missile’s longer range meant the submarines could patrol further from Soviet waters, increasing survivability. Once again, the Stimson had moved into the forefront of America’s strategic deterrent. For the men on board, the details of missile range and throw weight mattered less than the daily grind of operating a nuclear submarine, but they knew they carried the newest and most potent weapon in the arsenal.

In May 1982 she entered Newport News again for a second major overhaul. This one lasted until August 1984. When she returned to service, she was as modern as any boat in the fleet. Over the next eight years she would conduct twenty-eight Trident deterrent patrols out of Kings Bay, Georgia. Kings Bay had become the East Coast hub of SSBN operations, a sprawling base carved out of the marshes of southern Georgia. For the crews it meant new surroundings but the same old pattern: fly in, man the boat, vanish beneath the Atlantic. In December 1984 the Gold Crew conducted a Demonstration and Shakedown launch of a Trident missile, one of many launches that punctuated the long monotony of patrols. In 1988 the Stimson received another Meritorious Unit Commendation for her role in LANTCOOPEX 1-88, a rapid redeployment exercise that tested whether SSBNs could shift patrol zones quickly in a crisis. The exercise was a success, and the commendation recognized the professionalism of her crew.

Throughout these years, the commanding officers rotated but the mission remained constant. Men like Jortberg, Hall, Cruden, Smith, Powell, Conrey, Fitzpatrick, Keefe, Flenniken, and Johnson on the Blue Crew side. Weeks, Smith, Catola, Bell, Mueller, Showers, Plummer, and Towner on the Gold Crew side. Each brought his own leadership style, but the demands of the mission left little room for ego. The crews knew what was expected. Keep the boat ready, keep the missiles secure, keep the patrol on schedule. It was a job that required precision and discipline. One officer later said, “You had to trust every man on board because any mistake could compromise the whole mission. It was the most teamwork I have ever seen in my life.”

By the early 1990s the Cold War was over. The Berlin Wall had fallen, the Soviet Union had dissolved, and arms treaties were trimming the nuclear arsenal. The older SSBNs of the 41 for Freedom were being retired. The Stimson continued to patrol until May 1992, when her two crews were combined into one. For the sailors it was a sign that the end was near. On May 5, 1993, she was decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. The final “Plan of the Day” was printed, listing the simple events of a ship being taken out of service after nearly three decades. In 1994 she was dismantled at Bremerton, Washington, her reactor compartment sealed and stored, her steel recycled into new uses. It was an unceremonious end but in keeping with the life she had lived. Her mission had always been quiet, her presence unnoticed except by those who served on her.

What remains today is memory. The USS Henry L. Stimson Association keeps that memory alive, maintaining a website, preserving photographs, publishing newsletters, and holding reunions. Veterans share stories of long patrols, of sleeping in narrow bunks, of standing watches in the control room while the boat crept silently beneath the sea. They speak of the bonds formed in that environment, bonds that lasted long after the boat was gone. For many, serving on the Stimson was the defining experience of their lives.

Henry L. Stimson himself had once argued that the atomic bomb, terrible as it was, could be justified only if its possession prevented war. His logic carried over to the submarine that bore his name. The USS Henry L. Stimson never launched her missiles in combat. She did not need to. Her very presence deterred the enemy. She was a weapon designed to ensure that war never happened, and in that she succeeded. From her first patrol in 1967 to her decommissioning in 1993, she stood silent watch in the deep. Her story is a reminder that sometimes the greatest victories are the wars that never come.

The Cold War was filled with crises, from the Cuban Missile standoff to the tensions in Berlin and the long war in Vietnam. Through all of it, boats like the Stimson sailed their patrols. They were not glamorous. Their names rarely made the papers. Yet they were the bedrock of America’s nuclear strategy. A Soviet planner had to assume that somewhere beneath the ocean, a submarine he could not find carried missiles aimed at his homeland. That uncertainty was the foundation of deterrence. It was the quiet pressure that kept the balance of power from tipping into catastrophe. The sailors aboard the Stimson may not have been household names, but in their anonymity they carried out one of the most consequential missions in history.

When we look back now, it is easy to forget the fear that hung over the world during those years. Schoolchildren practiced duck-and-cover drills. Politicians spoke of nuclear winter. Families built fallout shelters. Against that backdrop, the Stimson and her sisters went to sea, unseen but always there. They were a reassurance to Americans and a warning to adversaries. They lived in the shadows so the rest of the world could live in the light.

From her keel laying in 1964 to her dismantling thirty years later, the USS Henry L. Stimson embodied the paradox of nuclear weapons. She was built to carry tools of unimaginable destruction, yet her mission was peace. She bore the name of a man who had grappled with the morality of atomic power, and she carried that legacy through every patrol. She represents the men who served in the Silent Service, who spent their youth in steel hulls beneath the sea, who accepted the burden of responsibility so that others might never face war. Her story is one chapter in the larger history of the Cold War, a chapter not of battles fought but of battles prevented. And in the end, that may be the most important history of all.

Are you a Stimson Crewmember? Check out the reunion site –> SSBN655.org

The USS Henry L. Stimson Facebook Group is –> HERE

Leave a comment