In the fall of 1903, when most of the world still thought of submarines as either science fiction or sideshow curiosities, the United States Navy quietly brought one into active service. The boat was called USS Plunger, officially Submarine Torpedo Boat Number Two. She was a stubby little creature, barely sixty-four feet long, powered by a gasoline engine that filled her insides with the stench of fumes, and armed with a single torpedo tube that, on paper at least, made her a weapon of war. On September 19, 1903, she was commissioned at New Suffolk, New York. That date puts her right at the beginning of America’s real experiment with undersea craft, and though Plunger would never fire a shot in anger, she would change the trajectory of naval warfare.

The Navy had already dabbled with USS Holland, the first commissioned American submarine, but Holland was a prototype, a proof of concept. Plunger was the first attempt at turning that concept into a class. She was built by Crescent Shipyard at Elizabethport, New Jersey, under contract to the Electric Boat Company, itself the brainchild of Irish immigrant John Philip Holland. Plunger’s design followed Holland’s ideas, but she was slightly larger and stronger, part of a batch that would later be redesignated the A-class. At first glance she looked like a steel cigar with a conning tower, and in truth that is exactly what she was. She displaced about 107 tons on the surface and a little more submerged. She could make eight knots on the surface and about seven underwater. That doesn’t sound like much, and it wasn’t, but nobody else’s submarines were any better. The French, the British, and even the Russians were experimenting at the same time with craft of similar size and speed. This was bleeding edge technology at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Inside Plunger was a world both fascinating and miserable. She was powered on the surface by a gasoline engine that drove one screw. Below the surface, an electric motor fed by batteries took over. Charging the batteries meant running the gasoline engine with the boat on the surface. There was no ventilation system to speak of, which meant fumes filled the interior. Sailors who served aboard remembered headaches, dizziness, and nausea as part of everyday life. The engine was loud, the hull sweated condensation, and the cramped quarters made privacy impossible. A crew of seven officers and men squeezed into this space, living and working in conditions that would make later submariners nostalgic for the so-called luxury of their World War boats. But Plunger’s men knew they were pioneers. Every dive, every experiment, every mishap became a data point for the Navy to learn what worked and what didn’t.

Plunger’s early years were spent at the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island. There she acted as an experimental craft, testing out diving routines, torpedo firing procedures, and the practical realities of undersea operations. The Navy was still trying to figure out whether these machines were toys or tools, and more than once there was skepticism about whether submarines could ever play a serious role in naval warfare. Yet the boat kept proving her worth as a training platform. Torpedoes could be fired from underwater. Crews could be trained to take a boat down and bring her up again in a controlled manner. Plunger was not a frontline asset, she was a floating classroom.

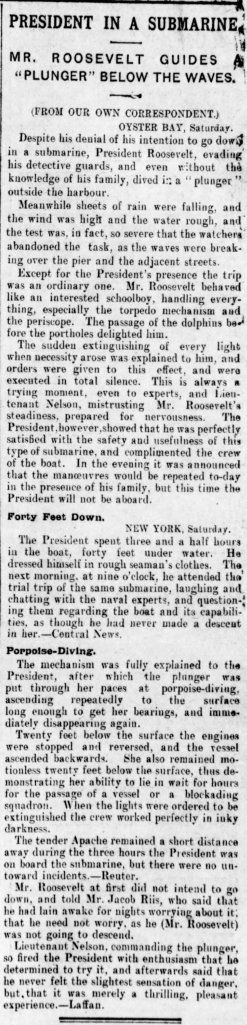

Then came the moment that put her on the front page. In August 1905, Theodore Roosevelt, the sitting President of the United States, climbed aboard Plunger off Oyster Bay and took her down for a dive. Roosevelt was not one to shrink from adventure. He had already ridden with the Rough Riders, charged up San Juan Hill, and hunted in the Dakotas. When he heard about these strange little submarines, he wanted to see one for himself. The Navy arranged for him to embark on Plunger, and with photographers on hand, Roosevelt descended beneath the surface of Long Island Sound. He was the first American President to dive in a submarine, and his presence aboard was a deliberate signal to the public and to Congress. If the Commander in Chief thought submarines were worth his time, then funding them was no longer in question. Roosevelt came back from the dive enthusiastic, declaring that the submarine would be a weapon of the future. Overnight, the perception of these craft shifted. What had been novelties suddenly had the President’s endorsement.

That single event was perhaps Plunger’s greatest contribution. She never fought a battle. She never patrolled hostile waters. She never sank an enemy ship. But by carrying Roosevelt beneath the waves, she secured the future of submarine development in the United States. From that point forward, the Navy accelerated its undersea program. New classes were ordered, designs were refined, and the path that would eventually lead to fleet submarines of World War II and nuclear-powered giants of the Cold War had been opened.

Still, Plunger’s service continued quietly. After Newport she was moved to Norfolk, then later to the Reserve Torpedo Division at Charleston. By 1909 she was still considered useful enough to merit command by a promising young officer named Chester W. Nimitz. Ensign Nimitz, who had graduated from Annapolis in 1905, was assigned to submarines early in his career. He briefly commanded Plunger, then moved on to other early boats like C-5. The experience he gained in those small, dangerous craft shaped his view of submarines as a vital part of naval power. Decades later, of course, Nimitz would command the entire Pacific Fleet in World War II, sending hundreds of submarines into battle against Japan. It is no exaggeration to say that the lessons he first learned aboard Plunger were seeds of that future.

Plunger was renamed A-1 in November 1911, part of the Navy’s reclassification system as more submarines entered service. She was stricken from the Navy list in 1913, already obsolete by rapid advances in design. Larger and safer submarines were being built, with diesel engines replacing gasoline, better ventilation, more range, and more endurance. Plunger could not compete. For a time she lingered as a hulk, then was assigned as “Target E” and deliberately sunk in New Suffolk in 1918. She was later raised, and in January 1922 she was sold for scrap. Her career had lasted less than a decade, but that was typical of early submarines. They were experimental platforms more than warships, disposable once the next design came along.

To measure Plunger’s accomplishments by tonnage sunk or battles fought is to miss her point. She was never about combat success. She was about proof of concept, training, and public relations. She proved submarines could work. She trained the first generation of American submariners. She carried the President of the United States below the waves, making submarines respectable. She gave Chester Nimitz his first taste of command. She represented the moment when the U.S. Navy stepped from theory into practice, from the drawing board into steel.

Think about the world in 1903 when she was commissioned. The Wright brothers had just flown at Kitty Hawk that same December. Automobiles were sputtering into existence. Electricity was transforming cities. It was an age when new inventions were bursting into daily life, and people weren’t sure which ones would last. Some thought submarines were a fad, a dangerous gimmick. Yet Plunger proved they were here to stay. The men who served aboard her endured headaches from gasoline fumes, the choking atmosphere of a steel tube, and the ever-present risk of disaster. There was no precedent, no handbook, just trial and error. They were guinea pigs, and they knew it, but they also knew they were part of something bigger than themselves.

It is easy to romanticize these early boats, to see them as quaint relics. But they were deadly serious machines. A single mistake could mean drowning for all aboard. Ballast tanks had to be managed carefully. Battery fumes could explode. Gasoline leaks could ignite. Torpedoes were unreliable and dangerous to handle. There was no rescue service, no deep-sea salvage technology. If Plunger had gone down and not come up, she would have been written off as another tragic experiment. That she did not suffer such a fate is a testament to the caution and skill of her crews.

Plunger’s legacy lived on in the Navy’s institutional memory. Every time the fleet launched a new class of submarines, officers and engineers remembered the lessons of those first Holland and Plunger-class boats. How to manage ballast, how to ventilate, how to organize the crew in a confined space, how to handle torpedoes, how to think about undersea tactics. Later boats would have better endurance, bigger crews, safer engines, but the DNA of those improvements can be traced back to Plunger’s cramped hull.

At that time she was assigned to the First Submarine Flotilla, based at the New York Navy Yard, joining sister-ships Porpoise (SS-7), and Shark (SS-8).

Among the ships in the background is the then decommissioned battleship Massachusetts (BB-2). The Massachusetts had her cage mast installed sometime in 1909. (NAVSOURCE)

In the larger sweep of naval history, Plunger represents the awkward adolescence of submarine warfare. Before her, submarines were oddities. After her, they became institutions. She bridged the gap between experiment and expectation. She gave the Navy confidence to order more boats, train more men, and think seriously about how undersea power might shape a future war. By the time World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, submarines were already a terrifying weapon, used by Germany to sink merchant ships and challenge even the Royal Navy. The United States would eventually build its own fleet of submarines, and when World War II came, they would become the silent service that strangled Japan’s maritime lifelines. It all goes back to those first tiny boats like Plunger.

So when we look back at September 19, 1903, the date of Plunger’s commissioning, we are not celebrating a combat record or a string of battle stars. We are marking the beginning of a tradition. Submarine sailors trace their lineage to her. The Silent Service owes her a debt, because she was where the learning began. Theodore Roosevelt’s presence aboard was more than a photo opportunity. It was a statement that submarines belonged in the Navy’s arsenal. Chester Nimitz’s time in her conning tower was more than a junior officer’s billet. It was the shaping of a mind that would one day lead the most decisive undersea campaign in history.

Plunger ended her days as scrap metal, forgotten in her time. But her influence echoes every time a submarine slips beneath the waves. From the cramped gasoline-fumed chamber of SS-2 grew the mighty nuclear fleet that now prowls the oceans. Submariners know that history. They know it started in boats like Plunger, with men who took risks so others could learn. The world may have forgotten her, but in the annals of the Silent Service, she stands at the threshold, a pioneer whose contribution cannot be measured in ships sunk but only in the doors she opened.

That is the story of USS Plunger. Not glamorous, not heroic in the Hollywood sense, but foundational. A boat that smelled of gas and sweat and steel, that dove with a President aboard, that trained the first generation of men who would one day fight beneath the seas. Commissioned on a September day in 1903, gone two decades later, but never really forgotten. History remembers her not for what she destroyed, but for what she created. A future. A tradition. A Navy that could fight beneath the waves.

Naval History and Heritage Command. Plunger I (Submarine Torpedo Boat No. 2). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Accessed September 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/p/plunger-i.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. Historic Ships: Presidential Intervention. Naval History Magazine, August 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2018/august/historic-ships-presidential-intervention.

Naval History and Heritage Command. Early Submarine Development: The Plunger Class. Photographic Section. Accessed September 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh/nh-102000/nh-102493.html.

PigBoats.com. The A-Boats (Plunger Class). Accessed September 2025. http://pigboats.com/subs/plunger.html.

Theodore Roosevelt Center. Roosevelt Takes the Plunge. August 2005. Accessed September 2025. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o123456.

Wikipedia contributors. “USS Plunger (SS-2).” Wikipedia. Last modified September 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Plunger_(SS-2).

Leave a comment