The story of the USS Von Steuben begins, fittingly, with a name from the Revolutionary War. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben (born September 17, 1730), was the Prussian officer who made Washington’s ragged army into something resembling a fighting force. It was his drill manual, delivered in blunt and precise language, that gave Americans discipline when they needed it most. Two centuries later, another Von Steuben was commissioned into service, this one made of steel and reactor power, carrying sixteen ballistic missiles rather than a musket and bayonet. Her purpose was no less vital. She was built to keep the peace by being invisible, silent, and ready to deliver destruction if the order ever came.

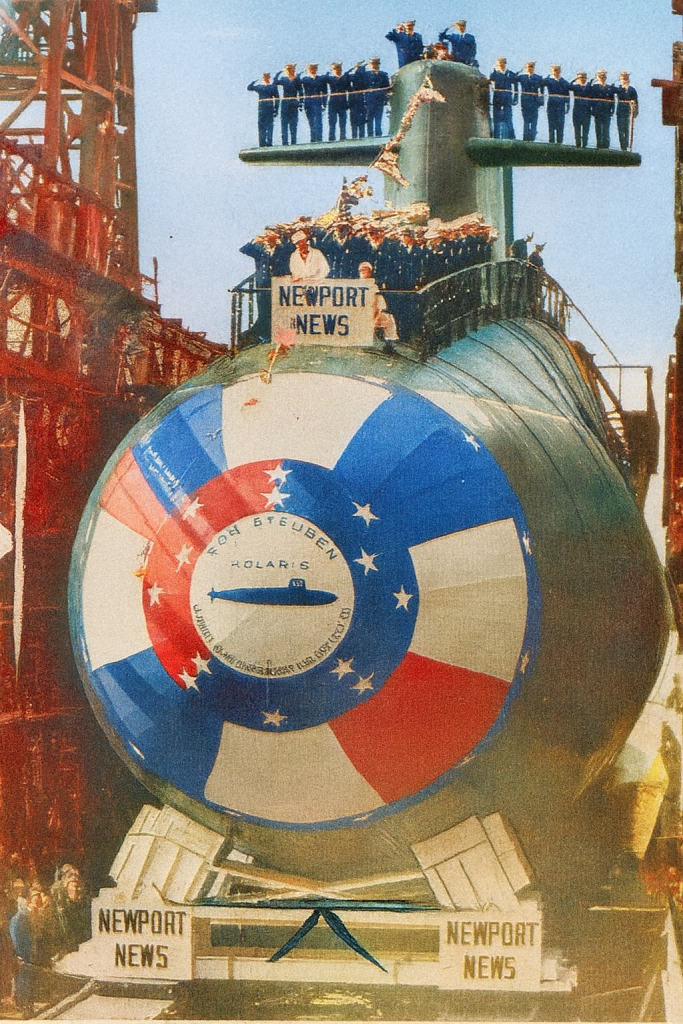

She was laid down at Newport News on September 4, 1962. The yard was already practiced at the art of building nuclear submarines, but each boat still carried a sense of weight. Launch day, October 18, 1963, drew the usual mix of dignitaries and crew families. Margaret Steuben, a descendant of the baron himself, sponsored her. Sailors who were assigned to her commissioning crew still tell stories of those early days in the yards, when welders’ torches and grinding wheels seemed to never stop, and the boat felt more like a construction site than a ship. On September 30, 1964, she was commissioned into the fleet. Captain John H. Nicholson took command, and the dual crew system, Blue and Gold, began their rotation. The James Madison class was an evolution of the Lafayette design, carrying Polaris A-3 missiles with longer range than the early models. She was one of the “41 for Freedom,” the backbone of America’s Cold War deterrent.

The first patrols began out of Charleston and Rota. For the sailors, the initial experience was jarring. One man, a young seaman fresh from training, remembered his first dive: “The klaxon sounded, the boat tilted, and I realized this was it. No windows, no horizon, just steel and faith.” Patrols lasted about seventy days. The cycle was simple and brutal: refit, load stores, load missiles, then vanish into the Atlantic for two months. Crews rotated every patrol. Blue would take her out, Gold would train on shore, then swap. Sailors at reunions still joke about which crew kept her cleaner, which crew cooked better chow, which crew had the better poker players. Rivalry kept the standards sharp.

Life aboard was a narrow world. Racks stacked three high, ventilation fans always droning, a constant hum from the reactor machinery. Watches ran four hours on, eight off, though the off time was often filled with maintenance or drills. Meals were quick and plain, except on steak night or when the cooks managed to surprise the crew with fresh fruit after a port call. Midrats at two in the morning—burgers, eggs, or chili—were as important as any system check. One sonar tech remembered the endless hours of listening: “Mostly merchant shipping. Sometimes a fishing trawler. Now and then, something that made you sit up straight. The ocean has a sound all its own, and after a few weeks you swear you can hear it breathing.”

In April 1968, routine sea trials turned dangerous. Off the coast of Spain, Von Steuben fouled the towline of the tanker Sealady. The collision was sudden. Crew accounts describe a violent jolt, men thrown against bulkheads, alarms screaming. “I thought we’d been hit by a torpedo,” one sailor later said. Damage control parties rushed to their stations. The boat survived, shaken but afloat. The collision was investigated, lessons were learned, and the boat was repaired. For those who lived through it, the memory never faded. “It taught me how thin the line was,” a machinist’s mate recalled. “We thought we were untouchable, but the sea has a way of reminding you who is boss.”

In 1970 she entered overhaul at Newport News for conversion to carry Poseidon C-3 missiles. The process was long and frustrating. Crews lived ashore, worked in the yards, and waited for the day when their boat would come back to life. Poseidon was a leap forward—multiple warheads, longer range, more accuracy. When she finally went to sea again, shakedown tests included DASO missile launches. One petty officer said, “The first time I saw a Poseidon leave the tube, I understood why we put up with the drills, the inspections, the endless training. That missile meant business.”

Patrols resumed, and so did the rhythm. Blue and Gold kept trading. Charleston remained a homeport, and Rota served as the forward base. Reunions today are filled with the small stories that made those years tolerable. The time the cooks managed to make pizza, even if it was soggy. The time the COB caught sailors sneaking a radio aboard and made them run extra drills. The way the mess deck arguments about music or baseball carried on for weeks because nobody had new scores or news. The ocean outside never changed, but inside, personalities clashed and bonded until the crew became something tighter than family.

By the early 1980s Von Steuben went through another conversion, this time to carry Trident I C-4 missiles. This shifted her homeport to Kings Bay, Georgia, a brand-new base built to support the Trident fleet. For some sailors, this was the hardest transition. They had grown used to Rota, to Spain, to the rhythm of Mediterranean patrols. Now they faced the humid heat of southern Georgia and a new set of routines. But the boat adapted, as did her crews. Trident brought even longer reach, tying the submarine into a new strategic web that covered the globe. One sailor joked, “We went from being a rifle to being a cannon.”

Through the Reagan years, Von Steuben made patrol after patrol. The world outside saw headlines about arms talks, summits, and tensions. Inside the boat, sailors just saw the next watchbill. The mission never changed: stay hidden, stay ready, stay alive. For the crews, the hardest part was the monotony. “It wasn’t fear,” said a former missile tech. “It was boredom. And that boredom was broken by sudden moments of intensity, a drill, an alarm, something that jolted you awake. You lived on edge between routine and the thought that one day the order might come.”

The Cold War ended, and so did Von Steuben’s career. On February 26, 1994, she was decommissioned and stricken from the register. She was sent to Bremerton for the Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program, and by March 30, 2001, she was gone. Pieces of her steel were melted down, her reactor disposed of. The boat that had spent thirty years in silence simply disappeared.

Her memory lives on in photographs at NavSource, in high-resolution Navy archives, in DANFS entries, and most of all in the crew who gather at reunions. They tell the same stories, laugh at the same jokes, and mourn the shipmates on the Eternal Patrol list. To them she is not just hull 632. She is the boat where they grew up, the place where they learned trust, the steel that taught them discipline.

Like the Prussian who drilled Americans into soldiers, Von Steuben drilled her crews into submariners. She demanded everything—time, patience, sweat, nerves—and gave in return a bond that lasted for life. She never fired her missiles in anger, but her presence made sure those missiles were never needed. In the end, that was the victory. The men who rode her can say, without doubt, that their silent patrols bought peace, and that the USS Von Steuben did her duty.

Are you a Von Steuben crewmember? Check out the reunion website –> Von Steuben Reunion

And the SSBN-632 Alumni Facebook Page: USS Von Steuben (SSBN 632) Alumni

Got it — here’s the same list of citations without numbers:

Naval History and Heritage Command. Von Steuben II (SSBN-632). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/v/von-steuben-ii.html

NavSource Online. USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) Submarine Photo Index. http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08632.htm

HullNumber.com. USS Von Steuben SSBN-632 Crew Roster. http://www.hullnumber.com/SSBN-632

NavySite.de. Crew List: USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632). http://www.navysite.de/ssbn/ssbn632crew.htm

USS Von Steuben Association. Reunion Website and Eternal Patrol List. http://www.ussvonsteuben.com

NavSource Online. “Collision with tanker Sealady, April 1968” entry within Photo Index. http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08632.htm

Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program. Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA). Ship-Submarine Recycling Program Fact Sheet. https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Home/Ship-Submarine-Recycling/

GlobalSecurity.org. SSBN-632 Von Steuben – James Madison Class Ballistic Missile Submarine. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/ssbn-632.htm