In the summer of 1920, the United States Navy had a new submarine to boast about. USS S-5, hull number SS-110, was one of the latest S-class boats, built not just for coastal defense but for true blue-water operations. She measured 231 feet in length, with a beam just shy of 22 feet, displacing 876 tons on the surface and 1,092 tons when submerged. She carried four 21-inch bow torpedo tubes, a 4-inch deck gun, and a crew of thirty-eight men. The S-class boats represented a new era of American submarine design, conceived during World War I and forming the backbone of the Navy’s undersea force through the 1920s. But with innovation came problems, and the S-5 carried a flaw that would prove decisive. Her main air induction valve, vital for sealing the submarine when diving, was notoriously hard to close.

The boat was laid down in December 1917 at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine, launched in November 1919, and commissioned in March 1920 under the command of Lieutenant Commander Charles M. Cooke, Jr. Early sea trials revealed the difficulty with the induction valve, but the S-5 pressed on. She was scheduled for recruiting visits to Baltimore and southern ports, with a goodwill itinerary that included Washington, Richmond, Savannah, and even Bermuda. On August 30, 1920, she departed Boston to begin that mission. Two days later, she was at sea off the Delaware Capes when her story turned from a recruiting cruise into a survival epic.

On September 1, Cooke ordered a crash dive to test her submergence speed. At the induction valve stood Gunner’s Mate Percy Fox, who for the briefest of moments let his attention wander. That hesitation was enough. When Fox realized the valve was still open, he yanked the lever so hard that the valve jammed, stuck wide. The ocean rushed in. Seawater poured into the control room, engine spaces, motor room, and forward torpedo room. The torpedo room had to be abandoned, flooding was uncontrollable, and the pumps failed when a gasket blew. The submarine pitched forward and sank to the bottom at 194 feet.

Inside the steel hull, thirty-eight men found themselves trapped with little hope of outside help. Hours passed into a full day. Air quality deteriorated rapidly. Vomit and human waste fouled the compartments, carbon dioxide levels rose, and seawater flooding the battery compartment produced poisonous chlorine gas. It was a horror show in steel, and yet the men did not surrender. Cooke and his officers devised a desperate plan. If they could blow air into the after ballast tanks, the stern might lift above the surface, allowing them to cut their way out.

The scheme worked. The stern rose until seventeen feet of hull protruded above the waves. But the next challenge was just as daunting. Using makeshift tools, the crew tried to cut a hole through thick submarine steel. After thirty-six hours of grueling labor, they had managed only a three-inch opening. An electric drill briefly offered hope but failed, forcing them back to hand chisels. At last they enlarged the cut enough to poke through a white undershirt tied to a copper pipe, a distress signal as pitiful as it was ingenious.

By fortune, the steamship Alanthus saw the odd sight and turned back. Not long after, the General G. W. Goethals arrived to lend aid. Sailors from both ships used real tools to open the hole wider, and a section of the submarine’s stern plating was cut out. As legend has it, when asked where they were bound, someone aboard the S-5 replied, “To hell, by compass.” That line may be more sea lore than fact, but it captures the spirit of the moment. By the early morning hours of September 3, every man aboard had been rescued. The cut piece of steel that freed them is preserved today at the National Museum of the United States Navy.

The submarine itself was not so fortunate. The little Alanthus tried and failed to tow the crippled boat. The battleship Ohio managed to get a towline secured, but it snapped, and S-5 sank again, this time to a final resting place fifteen miles off Cape May, New Jersey, in 160 feet of water. Salvage was attempted but the effort fell short. In late 1920 gales halted work, and in 1921 divers spent four months making nearly five hundred dives, using dynamite and concrete in vain attempts to stop the leaks. Finally the Navy admitted defeat and struck S-5 from the register.

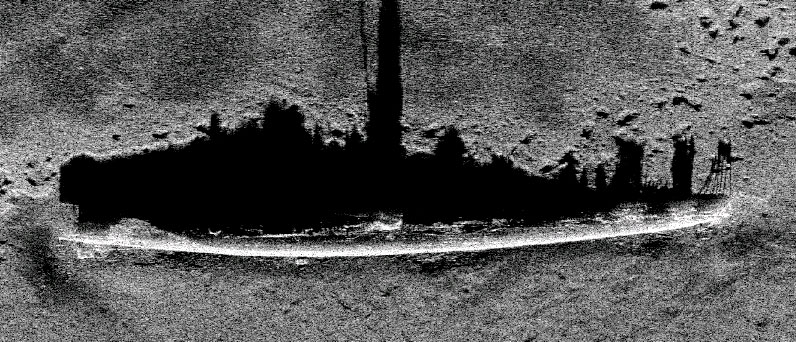

For eight decades she lay undiscovered. In July 2001, the NOAA ship Whiting surveyed the seabed using side-scan sonar, guided by accounts from fishermen and divers. After eight hours, the sonar lit up with the unmistakable outline of the submarine. The data was turned over to the Submarine Force Library and Museum in Groton, Connecticut, and the wreck of S-5 once again had a place in recorded history.

The tale of S-5 is remembered not as a combat loss, but as one of the most harrowing and inspiring survival stories in American submarine history. Thirty-eight men trapped in a steel coffin on the Atlantic floor survived because they refused to give in. Their resourcefulness, endurance, and courage stand as a reminder of the hazards of early submarine service and the resolve of the men who went below the sea. S-5 never fired a torpedo in anger, never patrolled a war zone, and never made a foreign port, but her story endures. It is a story of disaster, of improbable rescue, and of a submarine that, though lost, continues to speak through the memory of her crew’s survival.

Leave a comment