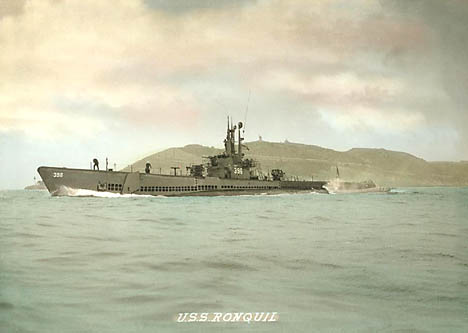

The USS Ronquil (SS-396) was a Balao-class submarine, one of the many steel predators the U.S. Navy sent into the Pacific during World War II. She carried the name of a humble spiny-finned fish from the waters of the Pacific Northwest, but her business was far from small. Commissioned on April 22, 1944, under the command of Lieutenant Commander H. S. Monroe, Ronquil’s steel frame stretched over 311 feet, her two propellers driven by the throb of Fairbanks-Morse diesels and Elliott electric motors. She carried ten torpedo tubes and a 5-inch deck gun, but what mattered most was the crew of eighty-one who would have to take her into combat and bring her back again.

Ronquil’s first war patrol began on July 31, 1944, after shakedown and training in Hawaiian waters. Her orders sent her north of Formosa and into the Sakishima Gunto, a hunting ground where Japanese supply convoys moved under heavy escort. It was a place where the stakes were always high, and the odds tilted against the hunter as much as the prey.

In the pre-dawn hours of August 23, Ronquil’s radar picked up a massive formation. Thirteen ships, screened by destroyers and patrol craft, pushing eastward in column. It was the kind of target submariners dreamed of, but it was also the sort of convoy that could turn into a nightmare if the escorts did their job. At 0350, Monroe brought Ronquil in for her first torpedo attack of the war. Six fish sped out from the forward tubes. The crew thought they heard five hits, but darkness, evasive maneuvers, and the quick reaction of Japanese escorts forced Ronquil deep before they could confirm the kill. When the noise of depth charges faded, the boat surfaced to shadow the convoy. That evening, at 1947, Monroe pressed his luck again. He maneuvered Ronquil into position and fired a spread at a freighter identified as the Freiburg, a vessel of about 6,700 tons. This time the crew watched smoke and flame rise from the target. The enemy ship slipped by the stern, crippled or worse. The men of Ronquil had drawn blood.

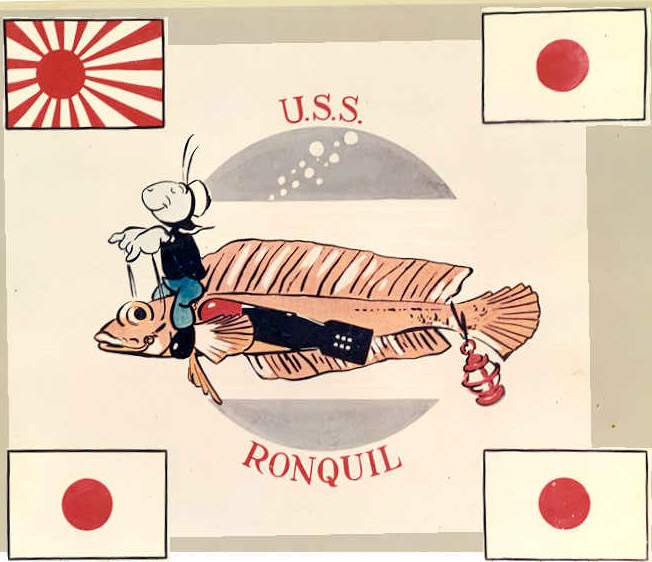

The next morning, the fight resumed. At 0640 Ronquil loosed a salvo at a destroyer, hoping to cripple one of the convoy’s guardians. One minute later, she shifted targets and fired at a large freighter. Then, at 0702, Monroe ordered another attack against a second freighter of nearly 4,000 tons. This time there was no doubt. Explosions thundered through the water and smoke lifted above the convoy. Ronquil had sunk two Japanese attack cargo ships: the Yoshida Maru No. 3, a 4,646-ton vessel, and the Fukurei Maru, weighing nearly 6,000 tons. The submariners listened to the rumbles of secondary explosions, confirmation that their torpedoes had found their mark. The Japanese escorts churned through the water, desperate to counterattack, but Ronquil’s crew knew their business. They dodged the patrol craft, rigged for silent running, and slipped out from under the net. When they came up again, the ocean was quieter, two enemy ships gone beneath it.

Ronquil pressed on with the hunt but found little else worth her torpedoes. She tried to finish off a destroyer, stalked a trawler, and took a shot at a smaller freighter, but none of these efforts bore fruit. By September 8, she was back from her first war patrol. Her captain reported her in excellent condition, her crew tired but proud. They had engaged large convoys under heavy guard and returned with confirmed sinkings to their credit. For the Navy, this was proof that Ronquil belonged in the thick of it.

Ronquil would make four more patrols before the war ended, earning six battle stars along the way. She went on to a long postwar career, from training cruises off California to Cold War deployments across the Pacific. In 1952 she underwent the “Guppy IIA” modernization, gaining a snorkel, streamlined hull, and updated electronics. She even had a brief Hollywood career, standing in for the fictional USS Tigerfish in the 1967 film Ice Station Zebra. In 1971, Ronquil’s American service ended when she was transferred to Spain, where she sailed as Isaac Peral (S-32) until 1984.

But her first taste of battle came in those August days in 1944, when the crew proved their mettle under the pressure of convoy action. They did what submariners had to do: get in close, fire straight, and then survive the counterattack. The ocean off Formosa still holds the wrecks of the Yoshida Maru and Fukurei Maru, silent testimony to the steel fish named Ronquil and her first patrol.

Leave a comment