In the early days of the twentieth century, when the United States was just beginning to understand the promise and peril of undersea warfare, a small, steel-hulled boat slipped into the waters of the Puget Sound. She wasn’t flashy. There were no cheering crowds on the dock and no headlines outside the Navy towns. But when USS F-3, originally named Pickerel, was commissioned on August 5, 1912, she quietly joined the ranks of a fledgling force that would one day shape the future of naval combat.

She was born in Seattle, built by the Moran Company (just south of where Coleman Dock Ferry Terminal is located today) as a subcontractor for Electric Boat, whose name was already becoming synonymous with submarine design. Her keel had been laid on August 17, 1909. By January 6, 1912, she was ready for launch, with Mrs. M. F. Backus performing the traditional duties of sponsor. Less than eight months later, F-3 entered commission under the command of Ensign Kenneth Heron.

Compared to today’s boats, she was modest in size and scope. Displacing 330 tons on the surface and 400 submerged, she stretched just over 142 feet. Her beam was narrow at 15 feet 5 inches, and she drew 12 feet of water. Propulsion came from a pair of NELSECO diesel engines coupled with electric motors. She could manage just over 13 knots topside and moved more slowly beneath the surface. Her four bow torpedo tubes gave her teeth, but she was more experiment than hunter.

(NAVSOURCE)

The F-class boats were new territory. Built on lessons learned from earlier C and D designs, the F boats carried innovations like bow planes and a rotating torpedo muzzle cap that reduced drag when submerged. The crew of 22 worked in tight, unrefined compartments. There were no permanent bridge structures early on, only temporary canvas covers rigged up for surface transit. These had to be stripped away before diving, making quick submergence out of the question. It was a hard life, and not for the faint of heart.

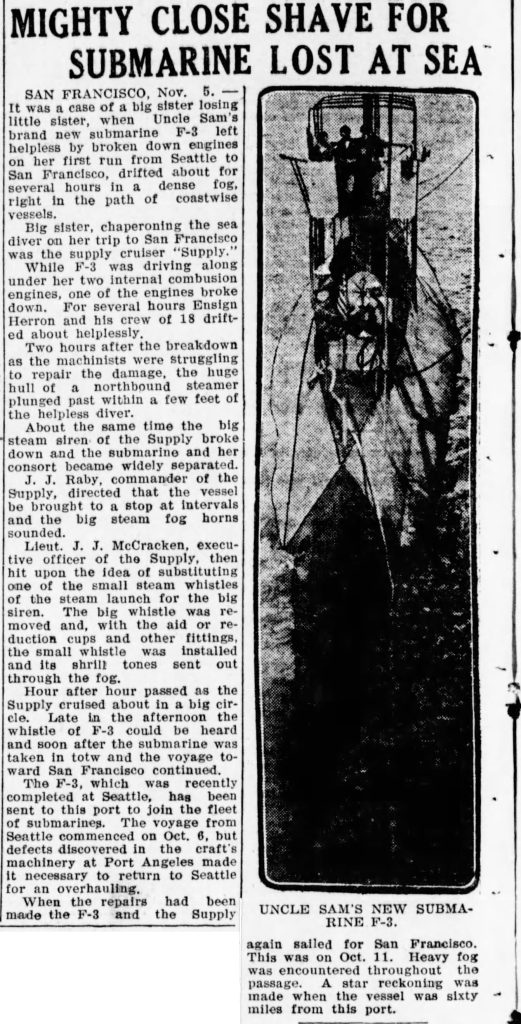

After completing her initial trials in the calm waters of Puget Sound, F-3 reported for duty at San Francisco in October 1912, joining the Pacific Torpedo Flotilla. Along with her sister boats, she trained off the California coast, diving, surfacing, and refining tactics that had barely moved beyond the drawing board.

In 1914, the entire flotilla was towed by armored cruisers to the Hawaiian Islands. It was a risky voyage, but deemed essential for expanding submarine operations in the Pacific. There, in the waters off Oahu, F-3 continued developing the basic doctrines of undersea warfare. She remained on station until November 1915.

On March 15, 1916, F-3 was placed in ordinary at Mare Island. The crew was released, and the boat was quiet. But the world was changing fast. War had already engulfed Europe, and American involvement was no longer a distant threat. When F-3 returned to full commission on June 13, 1917, the United States was already in the fight.

Reassigned to the Coast Torpedo Force at San Pedro, California, F-3 became a workhorse. She trained students from the newly formed submarine school, running daily operations both above and below the waves. It was during one of these exercises, on December 17, 1917, that tragedy struck.

While maneuvering off Point Loma, F-3 collided with her sister boat, F-1. The collision tore open F-1’s port side forward of the engine room. She sank in ten seconds. Nineteen men went down with her. Only three survived, rescued by the boats operating nearby. F-3’s bow was cracked in the collision, but she survived and was towed for repairs. It was a sobering moment. Submarine service was still young, and danger lurked not only from the enemy but from missteps in practice as well.

Once repaired, F-3 returned to service. For a time, she even supported a civilian motion picture company in experiments with underwater photography. It’s a detail that feels oddly modern, this blending of old steel with cinematic curiosity. In her final years, she continued operating out of San Pedro, training new submariners and staying ready, though never again pressed into front-line duty.

By 1922, her time was up. She was reclassified as SS-22 in 1920, then decommissioned on March 15, 1922. A few months later, on August 17, she was sold. No grand ceremony marked her departure. Like many early boats, her story faded into the margins of naval history.

But for those who served, and those who study the evolution of the Silent Service, F-3 matters. She was a product of Seattle’s shipyards, a pioneer in the Pacific, a survivor of wartime tragedy, and a classroom for future generations. The lessons she carried beneath the surface, and the lives shaped within her hull, echo quietly through time. Her story, like so many others in the early submarine force, deserves its place in the logbook of history.

Leave a comment