In the shadowy chess game of the Cold War, the move that changed everything did not come from a missile silo in Kansas or a bomber base in England. It came from beneath the waves, out of sight and far beyond reach. On July 20, 1960, deep beneath the Atlantic Ocean, the USS George Washington unleashed the first Polaris ballistic missile from a submerged submarine. That launch did not just mark a technical milestone. It transformed the rules of deterrence, and in many ways, helped hold off the unthinkable, even into the 21st century.

In the years following World War II, American military planners understood that the next war would be fought with different tools. The Soviet Union, once an uneasy ally, had emerged as a hostile superpower with nuclear ambitions of its own. The United States had demonstrated its destructive power at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but the reality of a two-sided nuclear standoff changed everything. If both sides could obliterate the other, what good was a first strike? That was the seed of deterrence, the idea that having weapons ready to strike back made the other side think twice.

But those weapons had to survive long enough to retaliate. Land-based missile silos could be mapped and targeted. Strategic bombers might be caught on the ground. Submarines, though, could hide in the vastness of the ocean, waiting quietly. That was the concept that lit the fire under what would become the Polaris program.

Before Polaris, the Navy had dipped its toe into the world of nuclear missiles with the Regulus program. The Regulus missile was a strange beast, basically a cruise missile stored in a hangar on the submarine’s deck. It had to be rolled out, prepped, and launched from the surface. That meant the submarine had to expose itself, revealing its position at the worst possible moment. It was bold, but not sustainable. The idea of a submarine that could strike while remaining invisible was still out of reach.

Then came 1956. That summer, a quiet meeting took place at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, under the banner of Project NOBSKA. A collection of scientists and naval officers gathered to talk strategy and technology. Among them was Edward Teller, already famous or infamous for his role in the hydrogen bomb. Teller shocked the room by saying he believed a one-megaton warhead could be made small enough to fit in a missile tube within five years. It was a bold claim, and not everyone believed it, but for the Navy, it was enough. The door to a new kind of missile was open.

Enter Rear Admiral William “Red” Raborn. Raborn was the kind of officer who did not wait around for permission. In November 1955, the Navy created the Special Projects Office and gave it one job: build a submarine-launched ballistic missile as fast as humanly possible. Raborn did not play by the old rules. He hired contractors instead of relying on Navy labs. He demanded impossible timelines and expected them to be met. Under his leadership, the Navy pushed forward with a system that had not even been invented yet.

The missile itself would be called Polaris. It had to be compact, powerful, and most of all, reliable. That meant using solid fuel instead of liquid fuel. Liquid propellants were volatile, messy, and dangerous, especially in the tight confines of a submarine. Solid fuel, on the other hand, was cleaner and could be stored safely for long periods. That one decision simplified the logistics and made the Polaris missile possible.

The engineering challenge was monumental. A two-stage missile with solid propellant had never been built for underwater launch. The team at Lockheed worked with Aerojet and other contractors to design the missile from scratch. MIT’s Instrumentation Lab took on the task of building an inertial guidance system compact enough to fit inside the missile, yet accurate enough to hit a target a thousand miles away. They pulled it off. The Mk. 1 guidance system weighed just 225 pounds, a miracle of miniaturization at the time.

Then there was the issue of launching from underwater. A rocket engine cannot just ignite inside a submarine. That would be suicide. Instead, the missile had to be ejected from its launch tube using high-pressure gas, a “cold launch,” and only then would the engine fire. It had to rise straight and true through the water, break the surface, and light up the sky.

While the missile took shape, the Navy had to figure out where to put it. Rather than wait for a whole new class of submarines, they took an existing nuclear attack submarine, the Scorpion, and split it in half. Into that gap, they inserted a new 130-foot missile compartment that held sixteen launch tubes. The result was the USS George Washington. The Navy called the missile compartment “Sherwood Forest” because the tall vertical tubes resembled a grove of trees. The ship launched in 1959, just as Polaris flight tests began in earnest.

Those early tests were not exactly smooth sailing. The first Polaris test launch in September 1958 failed. So did several that followed. But the team kept pushing. By 1959, they were seeing real success. The guidance systems worked. The rocket motors performed. The missile could fly hundreds of miles with deadly accuracy. Still, no one had tried it from a submerged submarine.

On July 20, 1960, all eyes were on the George Washington as she slipped beneath the waves. Far out in the Atlantic, the crew braced themselves. At the appointed time, the order was given. The launch tube filled with high-pressure gas. The missile rose, broke the surface, and roared into the sky. A second launch followed. Both missiles hit their targets with precision. The news spread quickly. America now had a weapon that could strike from anywhere on Earth, without warning. And the Soviets knew it.

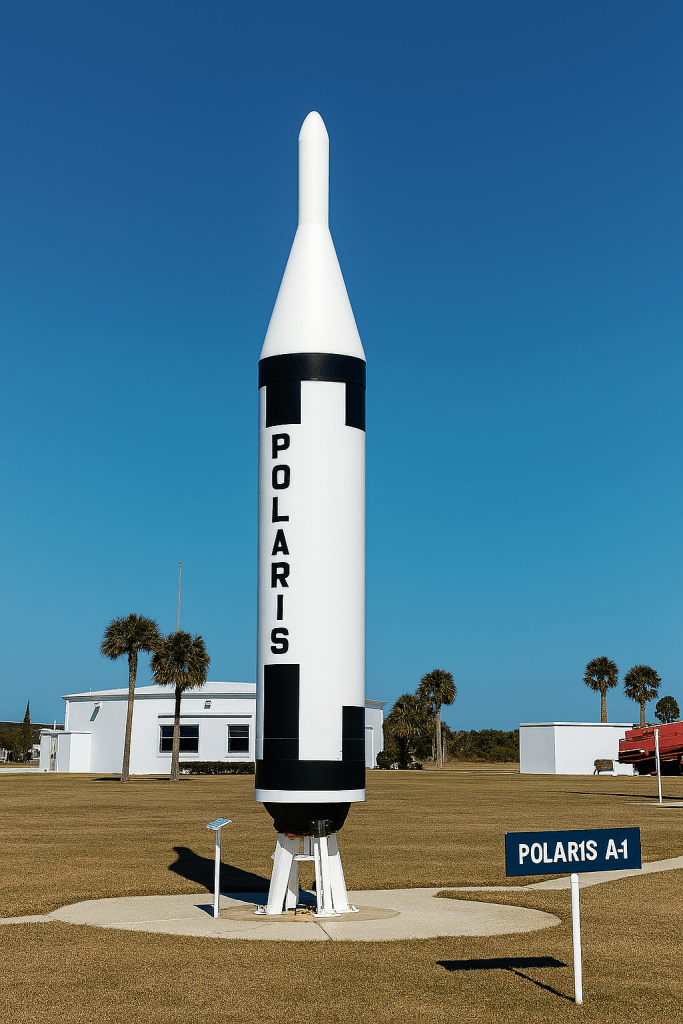

The implications were staggering. With one launch, the Navy had transformed nuclear deterrence. No longer were submarines a backup option. They were now the most survivable and most credible part of America’s nuclear triad. Within months, George Washington began her first deterrent patrol. She carried sixteen live Polaris A-1 missiles, each armed with a 600-kiloton warhead. She was joined by others, Patrick Henry, Theodore Roosevelt, and eventually, forty-one submarines in total. These became known as the “41 for Freedom,” the backbone of strategic deterrence through the 1960s and beyond.

Polaris was not perfect. Its range was limited to about 1,200 nautical miles. Its guidance system, though advanced, still left room for improvement. The missiles were accurate enough to hit a city, but not precise enough to target hardened silos or command centers. But that was the point. Polaris was not meant to strike first. It was meant to guarantee that no one could strike and get away with it.

Over time, newer versions of the Polaris missile extended its range and payload. The A-2 and A-3 models improved performance and added the ability to carry multiple warheads. Eventually, Polaris gave way to Poseidon and then Trident. But the legacy of that first launch remained.

It was not just a technical achievement. It was a statement. The United States had created a system so hidden, so resilient, and so terrifyingly effective that it made any thoughts of nuclear war seem suicidal. That was the grim magic of deterrence. Peace, held not by trust, but by the certainty of mutual destruction.

Behind the scenes, the success of Polaris also changed the way the military managed large projects. Raborn’s use of PERT, the Program Evaluation and Review Technique, revolutionized project management across the Defense Department. It allowed planners to coordinate thousands of moving parts and track progress in real time. That model would be used for everything from the Apollo program to modern defense procurement.

As the decades passed, the face of the Cold War changed, but the wisdom of Polaris endured. Submarine-launched missiles became the quiet cornerstone of America’s nuclear posture. Even today, with Trident missiles aboard Ohio-class submarines, the spirit of Polaris lives on beneath the sea.

The men who built Polaris did not just build a weapon. They built a shield. A quiet one. An unseen one. But a shield nonetheless. When the George Washington launched those missiles in 1960, she changed the world. Not with thunder. Not with destruction. But with silence, distance, and the promise that if attacked, America would respond from beneath the waves. That promise, whispered from the ocean’s depths, helped keep the world from burning.

And that is why July 20, 1960 matters. Because from the sea came not war, but a strange kind of peace. The kind only possible when the sword stays sheathed, but always within reach.

Naval History and Heritage Command. A Brief History of U.S. Navy Fleet Ballistic Missiles and Submarines. Accessed July 2025.

Gates, Robert V. “NSWCDD Blog – Polaris.” Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren Division, U.S. Navy, 2018. Accessed July 2025.

Polaris A-1 (UGM-27A) – Nuclear Companion: A Nuclear Guide to the Cold War. NuclearCompanion.com, September 10, 2023. Accessed July 2025.

Polaris A1. Astronautix.com. Accessed July 2025.

Polaris Missile. Encyclopædia Britannica. Last modified May 25, 2010. Accessed July 2025.

The Polaris Program. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (Science and Technology Review), Livermore, CA. Accessed July 2025.

“The News Tribune,” Tacoma, Washington. July 21, 1960, p. 26. Downloaded from Newspapers.com, July 18, 2025.

UGM-27 Polaris. Wikipedia. Accessed July 2025.

Leave a comment