Five and a half years ago, I was sitting at a table on a Saturday morning with one of our newest Base members at the time. He had been a Sonar Tech and was DBF to the core. As we talked about his story, he told me that his adventures had included going under the ice… in a diesel boat.

Look, I am fascinated by under ice ops, but the idea of a diesel boat going under the ice for more than a quick duck seemed… insane. He laughed. “It was, but we did it.”

At the time I had no idea about Operation Iceberg, the Navy’s 1946 expedition under the overall Operation Nanook, to send submarines into the Arctic Ocean. Tom (although he qualified in 1962 aboard USS Cutlass SS-478) wasn’t old enough to have been a participant, but he certainly would have understood it.

One of my least favorite parts of being a USSVI Base Commander were the Eternal Patrol notices and the funerals. Tom was a great guy, and I was looking forward to a lot more discussions about these kinds of things. But it wasn’t to be.

So this article is dedicated to the memory of STSCS(SS) Tom Lee, departed on Eternal Patrol on May 8, 2020.

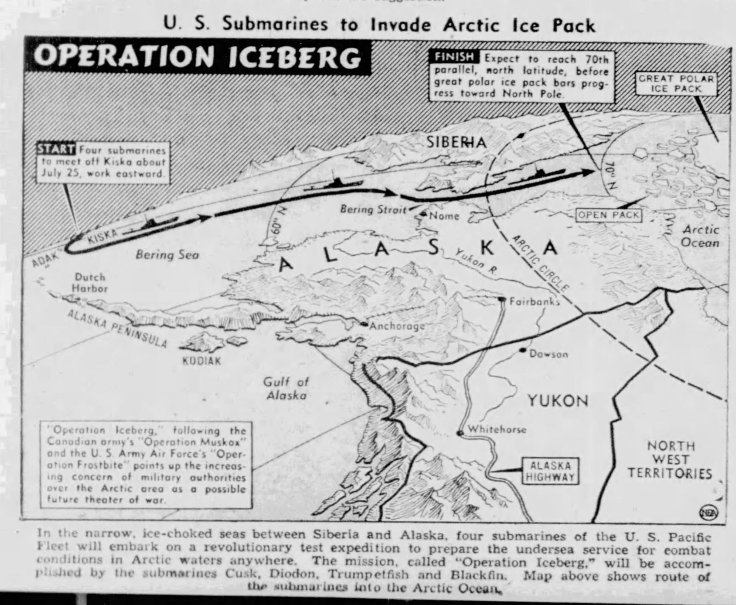

In the summer of 1946, just a year after World War II had ended, the United States Navy quietly launched an audacious mission into one of the most unforgiving environments on Earth. The operation was called Iceberg, and its objective was to explore whether American submarines could operate beneath the Arctic ice. While often confused with the far more publicized Okinawa invasion of 1945, which shared the same codename, this Operation Iceberg was a Cold War test of endurance, technology, and vision.

The backdrop was one of uncertainty. The wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union was already cracking, and the Navy saw the Arctic not just as a frozen wasteland but as a potential corridor for confrontation. The shortest path between the United States and Soviet Russia ran straight over the North Pole. The Navy needed to know if submarines could survive, navigate, and fight in this extreme environment. Operation Iceberg was their first answer to that question.

Though it operated under the Iceberg name, the mission was integrated with a broader initiative called Operation Nanook. Nanook focused on surveying Arctic waters, establishing weather stations, and testing equipment under polar conditions. But within that framework, Operation Iceberg sent submarines beneath the ice to do what had never been done.

Among the key vessels was USS Atule (SS-403), a fleet submarine that ventured under the pack ice of the Kane Basin, north of Baffin Bay. She was joined by USS Caiman (SS-323), another Balao-class sub. Supporting them on the surface were the Coast Guard icebreaker USS Northwind, the ice patrol ship USS Whitewood, and the seaplane tender USS Norton Sound. The latter coordinated with flying boats operating from Thule, helping scout ice floes and relay critical weather and ice data.

The mission was not a combat patrol. It was a trial by ice. The subs tested sonar effectiveness under ice, practiced emergency surfacing through thin ice, and experimented with navigation techniques in areas where magnetic compasses faltered. Dr. Waldo Lyon and the newly established Arctic Submarine Laboratory played a quiet but vital role in designing equipment and training crews for the harsh conditions.

The achievements were many. Submarines successfully transited under the ice without damage, gathered valuable oceanographic data, and identified critical areas for future Arctic navigation. The sonar data alone helped develop the under-ice navigation techniques still in use decades later.

They also learned hard lessons. Ice pressure stressed hulls more than anticipated. Navigating in low visibility under ice sheets demanded new thinking about sonar use and course plotting. The dependence on surface and aerial support reinforced the need for robust Arctic logistics, including the ability to supply and communicate with submarines far from standard bases.

The success of Operation Iceberg fed directly into Operation Blue Nose in 1947, where USS Boarfish pushed deeper into the Chukchi Sea, and submarines regularly operated under the ice. These early experiments became the foundation for what are now known as Ice Camp exercises. Today, Arctic surfacing is an annual test for American and allied submarines, with direct lineage to 1946.

Strategically, the Arctic became central to Cold War planning. The ability to hide, move, and launch from beneath the polar ice gave the United States Navy an edge that could not be matched by surface fleets. In time, missile submarines would follow, turning under-ice patrols into vital components of nuclear deterrence.

Operation Iceberg began as a question. Could submarines operate beneath the ice? The answer was yes. It was not glamorous. It was not widely reported. But in that frozen summer of 1946, a handful of sailors aboard a few steel boats gave the United States a new frontier to master. The legacy of that mission lives on every time a submarine breaks through the ice in the high latitudes, silent and unseen until it chooses to rise.

This was not just a test of machines. It was a test of men, of resolve, and of the Navy’s willingness to look beyond the horizon of war and into the cold unknown.

Leave a comment