She slipped into the water at Newport News on a warm August day in 1965, sleek and silent like the role she was built to play. But the USS George Washington Carver (SSBN-656) was more than just a machine. She was a symbol. Named for an African-American scientist who had turned peanut shells into salvation for poor farmers, she stood out in a fleet named for politicians, admirals, and mythic figures. Her sponsor, the legendary contralto Marian Anderson, broke another barrier when she christened the boat, the first African-American woman to do so. And when her first crew walked aboard, they knew they weren’t just stepping onto a submarine. They were becoming part of something bigger.

By the mid-1960s, the Cold War was seething. The Soviets were building up, we were building back, and beneath all the noise was the quiet thrum of deterrence. That was where Carver fit in. She was one of the last of the Benjamin Franklin-class boats, each of them a roaming launch pad for 16 Polaris missiles, each on silent patrol in the North Atlantic. The theory was simple but terrifying. If the enemy struck first, we could still strike back. And that second strike would come from boats like George Washington Carver, hiding in deep oceans, waiting for the order that everyone prayed would never come.

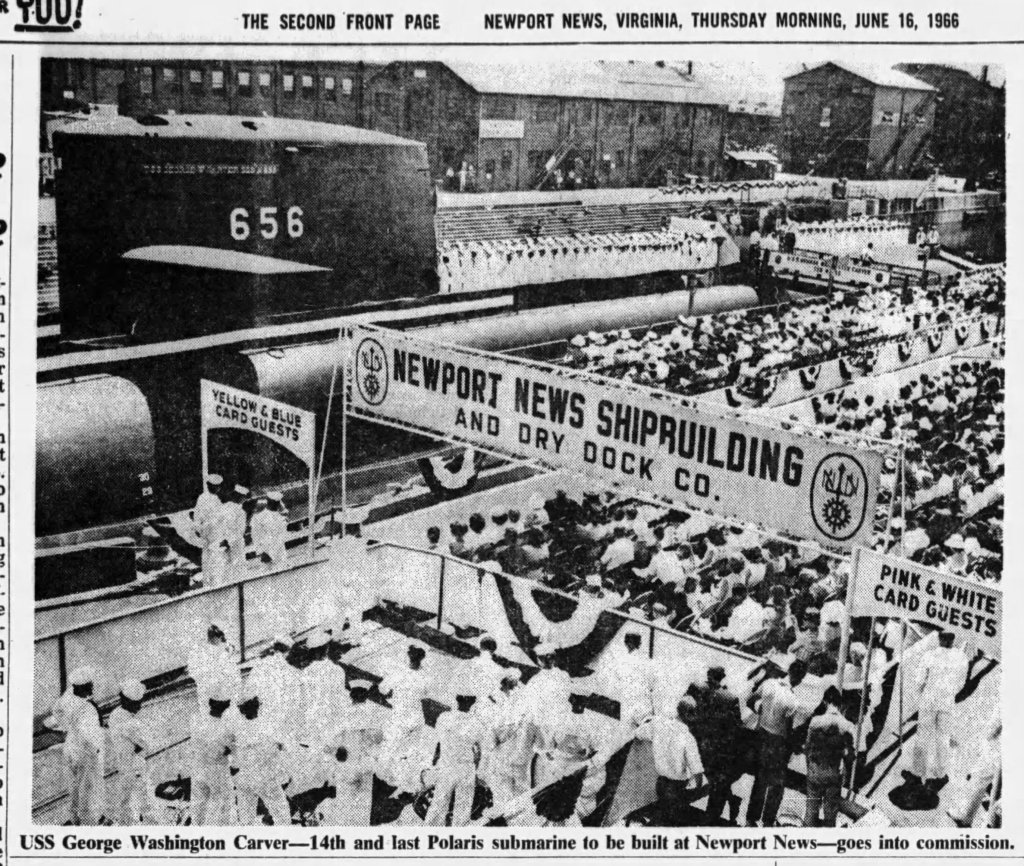

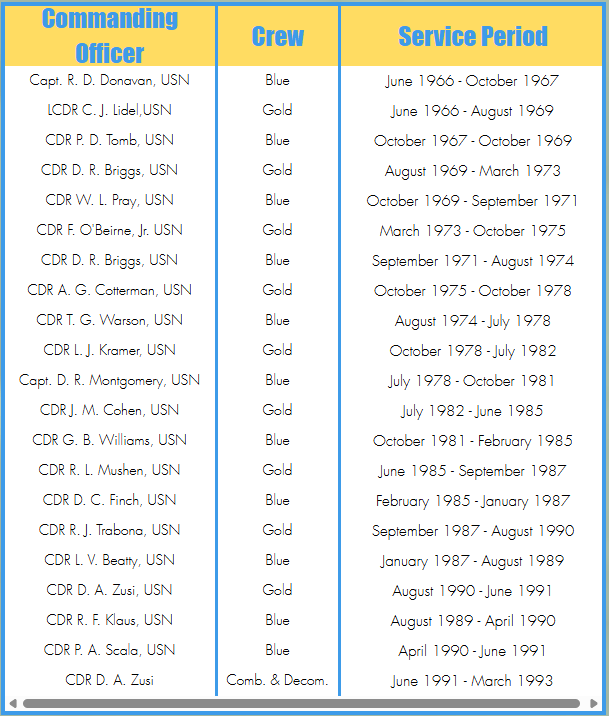

Commissioned on June 15, 1966, Carver was brought to life by two alternating crews. Commander R.D. Donavan took the Blue Crew, while Commander R.D. Stancil led the Gold. That dual-crew system was the key to the whole patrol cycle. While one crew trained and rested, the other took the boat to sea. They met in Holy Loch, Scotland, where the submarine tenders tied up like miniature cities and the mountains loomed in the distance like watchmen. From there, George Washington Carver departed on her first deterrent patrol in December of that same year, slipping past the green hills and into the cold grey of the North Atlantic.

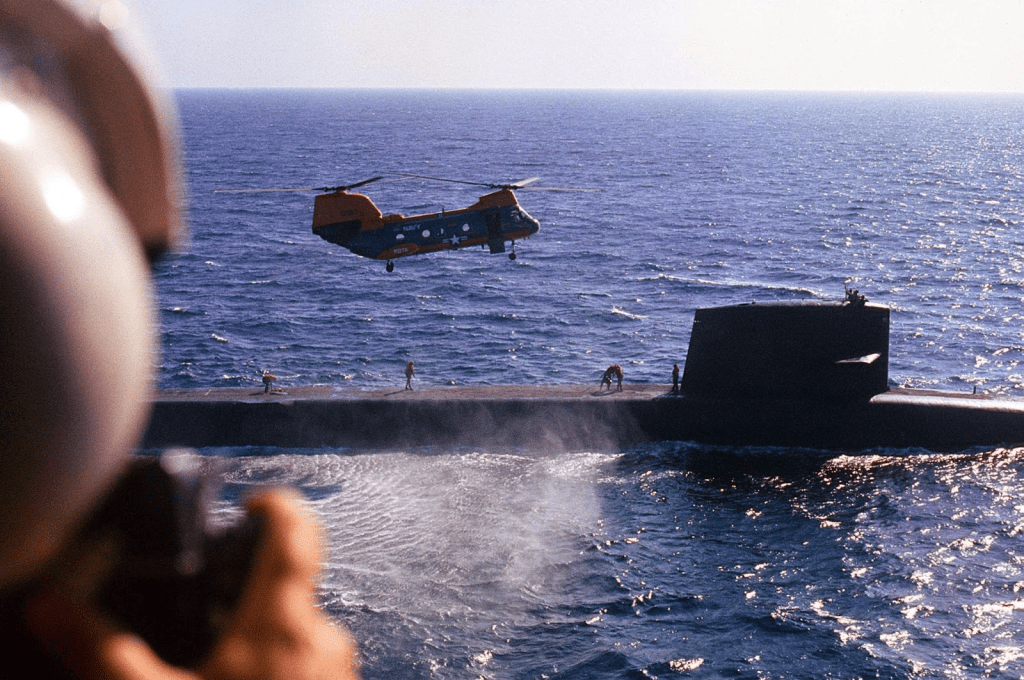

Patrols were long, repetitive, and secretive. The public never knew where she was, or when. That was the point. But her crews knew. They knew the hum of the turbines and the sting of the salt in the air when the boat surfaced to transmit. They knew the pressure of alert status, the long hours at sonar, the quiet clink of trays in the galley. They lived by drills and routines, knowing that the only thing worse than the boredom of patrol was the possibility that it might turn suddenly real.

By the early 1970s, Carver needed a breather. She underwent a major refueling overhaul in Groton, Connecticut. It wasn’t just about reactor cores. It was about new systems, new wiring, new life pumped into steel and circuitry. Overhauls are the hidden chapters of submarine life. Long months in drydock, pipefitters crawling over bulkheads, crew members rotating through schools and simulators. But when she came back, she was better than before. Ready again for the long, cold patrols.

Carver didn’t just disappear into the abyss. She had her moments in the light. In August of 1985, she surfaced off Cape Canaveral for a Poseidon missile test. Civilians were invited to watch from the USNS Range Sentinel. The launch was flawless. That moment, streaking skyward in a roar of flame, was the public face of deterrence. It reminded the world that the old girl still had teeth.

But by the end of the 1980s, the world was shifting. The Soviet Union was crumbling. Treaties were being signed. And the Navy was trimming down its SSBN fleet. George Washington Carver was nearing the end of her run. In 1991, her missile tubes were deactivated and filled with concrete. She was reclassified as an attack sub and quietly transferred to Submarine Base Bangor, Washington. For a brief time, she trained and served in a different capacity, a silent sentinel no longer carrying strategic missiles, but still carrying the pride of the force.

Her final days came in 1993. She was decommissioned and struck from the Naval Vessel Register in March of that year. Not long after, she entered the Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton. It was a tidy end. Respectful. She wasn’t scrapped in haste or discarded like junk. She was dismantled with the same care she’d been built. On March 12, 1994, her name was officially retired.

She lived nearly three decades, served through the peak and winding down of the Cold War, carried thousands of sailors, and upheld the mission with silence and dignity. Today, no monument marks where she lies. No museum displays her conning tower. But in the memories of her crew, and in the quiet history of Cold War victory, the USS George Washington Carver still looms large.

She was built for strength. She sailed with knowledge. And in every sense that mattered, she lived up to both.

Leave a comment