In the waning days of May 1959, as Cold War tensions simmered just beneath the waves of the North Atlantic, a diesel-powered submarine from the United States Navy quietly made history. The USS Grenadier, a Tench-class submarine commissioned after the Second World War and still active in the early nuclear age, was patrolling a particularly sensitive patch of ocean near the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap. This was no ordinary patrol. Intelligence analysts had begun to suspect that the Soviets were pushing their submarine forces westward, probing closer to NATO territory than ever before. For Admiral Jerauld Wright, the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet, it was a moment of opportunity wrapped in paranoia. He had issued an informal challenge to his undersea commanders: the first one to produce hard evidence of a Soviet submarine prowling the Atlantic would earn a case of Jack Daniels.

Lieutenant Commander Theodore F. Davis was not hunting whiskey, but he understood the stakes. His crew aboard the Grenadier had been at sea for several days conducting antisubmarine exercises when they picked up a sonar contact on the morning of May twenty-eighth. The signal was erratic, noisy, and unfamiliar. Davis knew almost immediately that this was not one of their own. The contact behaved like a foreign boat running on low batteries and likely snorkeling to maintain power. That behavior fit the profile of a Soviet Zulu-class submarine, one of the early ballistic missile carriers that Moscow had begun adapting from their World War II–era designs.

The Grenadier kept pace, silent and steady. The pursuit lasted well into the next day. Davis coordinated with a Neptune patrol plane overhead, passing coded instructions and predictions. He suspected the Soviet boat would need to surface. On the morning of May twenty-ninth, just past one o’clock, his hunch paid off. The Soviet submarine breached the waves, catching its breath. The Neptune’s camera clicked. The Grenadier’s sonar team confirmed the profile. It was a Soviet Zulu-class missile submarine, operating in the Atlantic, right where it should not have been.

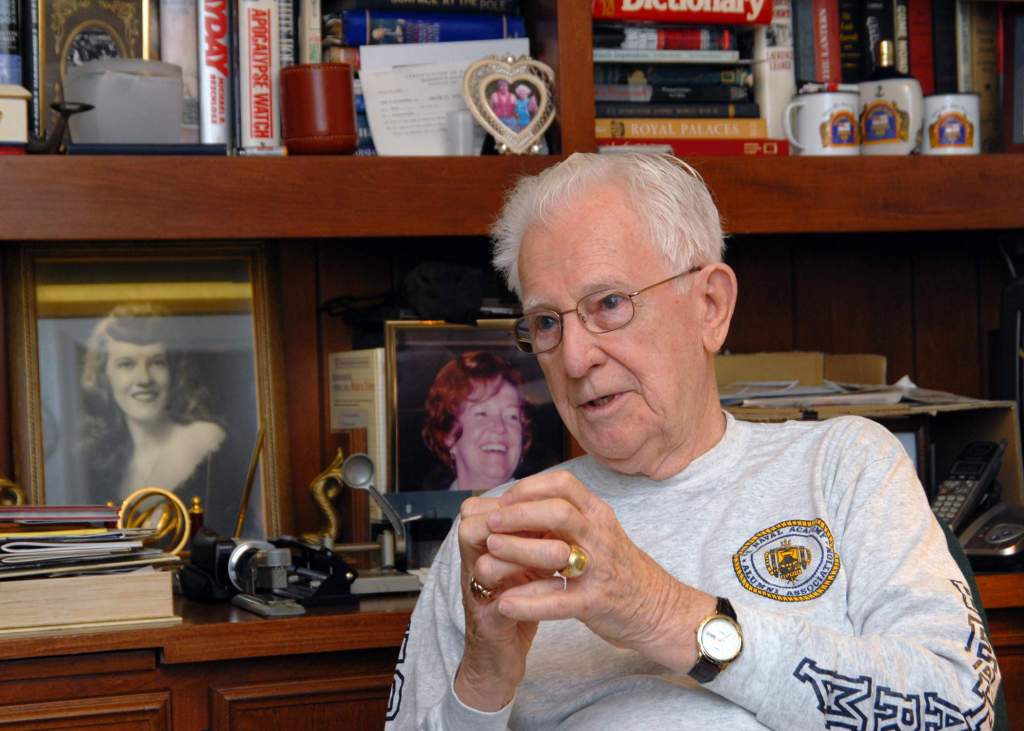

Davis, now confident, radioed his report in the form of a coded request. He asked Admiral Wright for delivery of the promised bottle. That bottle arrived in the form of an entire case. The moment was immortalized in a now-famous photo of the Admiral personally handing over the Jack Daniels to the crew of the Grenadier. It was a lighthearted conclusion to a serious moment. For the first time, the United States had visual, photographic proof that the Soviet Navy was operating strategic missile submarines in the Atlantic. That fact changed the tone of maritime strategy.

The larger implications were not lost on anyone in the Pentagon or the Kremlin. While the Soviets never officially acknowledged the incident (is is referenced in this 2020 article), internal records later revealed that the submarine involved was likely B-78, a Project 611 boat modified for missile operations. Its commander later recalled that the sub was indeed carrying ballistic missiles and had surfaced to replenish battery power, unaware of how close the Americans had come to making history.

The May twenty-ninth encounter was more than a tactical success. It was a signal that the silent service of the United States Navy could play chess as well as any admiral. The Grenadier’s crew had operated with precision, restraint, and clarity of purpose. They had not fired a shot, but they had outmaneuvered a nuclear adversary at the dawn of one of the most perilous chapters in naval history.

The Cold War would go on to see hundreds of similar encounters, most never publicized, many ending far less cleanly. But this one, with its photograph, its whiskey toast, and its quiet triumph, stood as a testament to vigilance, professionalism, and the peculiar gallows humor that sailors have always used to survive the deep.

Leave a comment