There was a time when submariners went to sea knowing that if disaster struck, they were likely never coming home. In the early days of the Silent Service, a sunken submarine was a steel tomb. Rescue was often impossible. Escape was unheard of. The ocean was merciless, and technology had not yet caught up to the bravery of the men who dared to ride beneath the waves. That is what made the invention and testing of the Momsen Lung on May 8, 1929, such a watershed moment in naval history. It was a turning point in the age-old struggle to wrest survival from the deep.

The man behind the Momsen Lung was Charles Bowers Momsen, known to many as “Swede,” though he was actually of Danish descent. He was not the kind of officer content to accept limitations, particularly when those limitations meant men died needlessly. By 1929, he had already served on submarines and had borne witness to two devastating losses that shaped his career and haunted his conscience. In 1925, the USS S-1 went down. Two years later, the S-4 was rammed by a Coast Guard cutter off Cape Cod and sank with forty souls aboard. Rescue divers could hear the trapped men banging on the hull. They could do nothing.

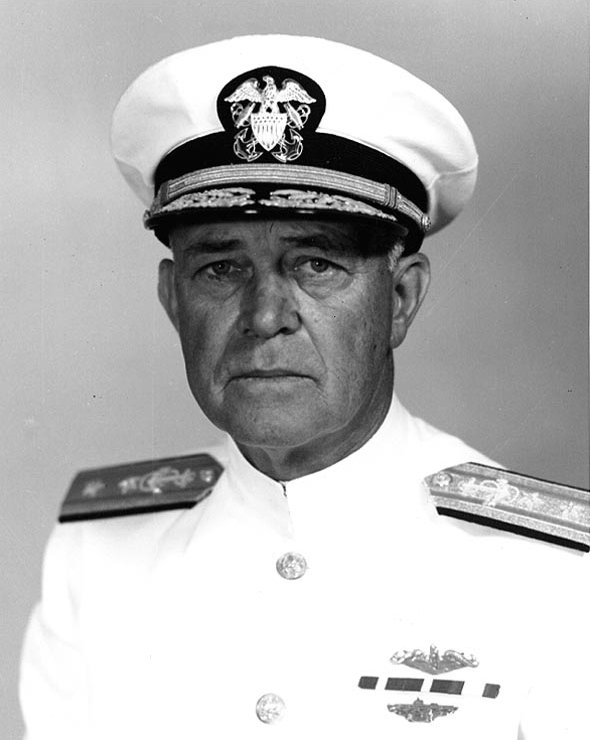

Public Domain

That kind of helplessness leaves a scar. Momsen was not interested in letting it happen again.

He began working on two tracks. One was a large diving bell that would evolve into the McCann Rescue Chamber. The other was a more personal solution—a compact breathing apparatus that a sailor could wear to escape a sunken boat on his own. That second idea became the Momsen Lung. It was a self-contained rebreather that recycled exhaled air, scrubbed out the carbon dioxide with soda lime, and topped it off with a small supply of oxygen. It was worn like a chest pack, with twin hoses leading to a mouthpiece and a clip to block off the nose. It looked odd, perhaps even comical, but it was deadly serious. It meant life.

Momsen was not alone in this mission. He worked alongside Chief Gunner Clarence Tibbals and civilian engineer Frank Hobson. The Navy was not exactly quick to embrace the device. In fact, early tests were done unofficially, off the books and on personal initiative. One of those first trials was in the Potomac River. Word of it reached the press, and public interest forced the Navy’s hand. Eventually, the brass relented. Testing ramped up. Drills followed. And on May 8, 1929, the Momsen Lung got its first real taste of the future. It worked.

In that test and the ones that followed, sailors would strap on the device, enter escape trunks, and exit into the open sea. Some trials were done from as deep as 207 feet. There were risks, to be sure. Two sailors lost their lives during training after failing to exhale during ascent—a reminder that the lungs, like balloons, do not tolerate pressure changes lightly. Still, the trials proved it could be done. And that was enough to begin issuing the device to the fleet.

Training was rigorous. Sailors practiced in escape tanks, in flooded compartments, in controlled but daunting conditions. They learned to follow ascent cables marked at intervals to ensure decompression stops. They counted their breaths to time their pauses. They drilled until it was muscle memory. Because if the time came, there would be no room for panic.

The Lung became standard issue on Porpoise- and Salmon-class submarines and remained in service through World War II. Its design evolved—hoses shortened, valves refined, the breathing bag repositioned for better comfort and performance. Crews gained confidence in the device, and while it was never perfect, it offered something submariners had never had before: a fighting chance.

In practice, however, the Momsen Lung saw surprisingly few actual uses. The most notable early incident was in 1939, when the USS Squalus sank off the coast of New Hampshire. The trapped crew used the Momsen Lungs as makeshift gas masks to survive the release of chlorine gas from their batteries. The real rescue came courtesy of the McCann Rescue Chamber, with Momsen himself overseeing the mission. Thirty-three lives were saved. It was a triumph.

Drawing by Lt. Cmdr. Fred Freemen, courtesy of Theodore Roscoe, from his book “U.S. Submarine Operations of WW II”, published by USNI.

The only known full escape with the Lung came five years later, on October 25, 1944. That was the day the USS Tang went down. She had a stellar combat record—thirty-three enemy ships sunk. But on her final patrol, a faulty torpedo made a circular run and struck Tang herself. The boat came to rest at 180 feet. Inside the crippled submarine, thirteen men attempted to escape using Momsen Lungs. Five made it to the surface and were later captured by the Japanese. The others perished. Some never left the boat. Some succumbed during ascent. One man had his mouthpiece knocked away. Another left the trunk without the device at all. The Momsen Lung gave them a chance, but not a promise.

There were criticisms of the device. It required composure under extreme stress. The physiological science behind it was not always well understood in its early days. Some called it a glorified death trap, arguing that it may have taken as many lives as it saved. That may be true. But it also gave crews hope. It gave them something to train for. It gave them belief. And for the Silent Service, belief matters.

By the 1960s, the Momsen Lung was replaced by the Steinke Hood—a simpler device, easier to use, more forgiving. Eventually, that too was replaced by the full-body Submarine Escape Immersion Equipment that is in use today. But every one of those devices owes a debt to Swede Momsen and his peculiar-looking lung.

His invention may have looked like a rubber bag strapped to your chest. But it carried with it the breath of life, the hope of survival, and the fingerprints of a man who refused to let good sailors die without a fight.

On May 8, 1929, the Silent Service took a breath. A real breath. And everything changed.

Leave a comment