The USS Grenadier (SS-210) was not just another submarine. She was part of the United States Navy’s silent force—a fleet of underwater hunters that prowled the vast Pacific during World War II. Built at Portsmouth Navy Yard and launched in November 1940, Grenadier was a Tambor-class submarine, a major leap forward in undersea warfare. These boats were longer, sleeker, and more heavily armed than their predecessors. At over 300 feet in length, with ten torpedo tubes and improved surface speed, Tambor-class subs like Grenadier marked the transition from coastal patrol vessels to long-range oceanic predators. They could travel over 11,000 miles without refueling and could strike deep behind enemy lines, changing the tempo of war at sea.

Grenadier began her service in early 1941, just months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. She quickly moved from training to frontline service, and by 1942, she was actively patrolling the waters off Japan, Formosa, the Dutch East Indies, and the South China Sea. Her second patrol saw the sinking of the Taiyo Maru, a Japanese transport carrying industrial experts to exploit resources in the occupied territories—a significant strategic loss for the Japanese war effort. Over the course of five patrols, Grenadier sank six enemy ships totaling over 40,000 tons and damaged two others. She even participated in the submarine patrol line at the Battle of Midway, part of a defensive net during a turning point in the Pacific War.

In March of 1943, Grenadier departed Fremantle, Australia, for her sixth and final patrol. She was tasked with hunting Japanese shipping in the Strait of Malacca, a vital artery between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. On April 20, she surfaced at night to pursue two enemy merchant ships. Just before sunrise on April 21, a Japanese plane spotted her. Grenadier attempted a crash dive, but as she passed 120 feet, two bombs exploded overhead. The lights went out. Power died. Fires ignited in the control cubicle. She came to rest on the ocean floor at 270 feet.

For thirteen agonizing hours, the crew fought to save the sub. A bucket brigade moved water by hand. Electricians struggled to restore power. The heat inside the boat was oppressive. Late that night, they managed to surface. But the damage was too severe. One shaft barely turned. With no real propulsion, the crew even attempted to rig a sail to the periscope in a desperate bid to reach land.

At dawn on April 22, two Japanese ships appeared. Commander John A. Fitzgerald made the difficult decision to scuttle Grenadier. The crew destroyed codebooks and sensitive equipment. They opened the vents. The boat flooded and slipped beneath the waves. The crew—76 men in all—was taken aboard a Japanese merchant ship and transported to Penang, Malaya.

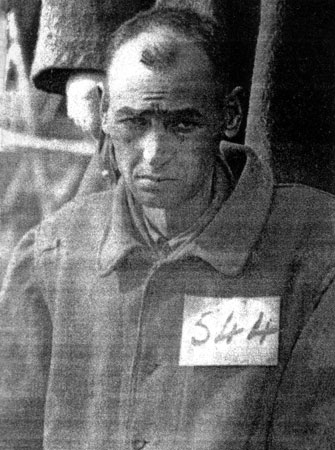

Machinist’s Mate, Second Class

Birth Date June 20, 1912

From Bremerton, Washington

Decorations Purple Heart, Prisoner of War Medal

Submarine USS Grenadier (SS-210)

Loss Date Died on February 21, 1944

Location Sunk near Penang; crew taken prisoner

Circumstances Died of acute pneumonia as a POW

Remarks Charles was born in Hoberg, Missouri. Photo was taken at Fukuoka POW Camp in Japan.

Photo courtesy of Steve Moore. Information courtesy of Paul W. Wittmer.

What followed was nearly two years of suffering. The crew of Grenadier was starved, beaten, tortured, and moved from prison camp to prison camp. Their captors demanded information. The men refused to give it. Their silence was their last act of service. Four crew members, including Machinist’s Mate Second Class Charles Freeman “Pappy” Linder, did not survive captivity.

Pappy Linder was more than a name on a casualty list. Born in 1912, he had worked for the Gas Service Company in Hutchinson, Kansas, before the war. He married Norine Wheeler, and together they had a daughter, Barbara Ellen. In January 1941, they moved to Bremerton, Washington, where Norine found work at Sears. Charles rejoined the Navy, driven by duty and love for his family. When Grenadier was lost, Norine remained in Bremerton. A cruel twist followed—months after Charles had died of pneumonia in the Fukuoka prison camp, Norine received a POW postcard in his handwriting, claiming he was in good health.

Today, Bremerton remembers him not just as a sailor, but as a member of our community. Though Norine and Barbara eventually left the area, the Linder family’s legacy continued. Charles was the cousin of Paul Linder, a longtime educator, principal, and superintendent in the Central Kitsap School District, and the namesake of the Linder Foundation that supports local education. The family’s contributions—both in service and in schools—run deep in Kitsap County.

The wreck of Grenadier may have finally been found. In 2019, a team of divers located a submarine-shaped silhouette 270 feet beneath the waters of the Strait of Malacca. Its dimensions and features match Grenadier exactly. Though no nameplate has yet been found, the evidence is strong. It is a fitting coda to a story long hidden beneath the waves.

But this is not just a story about a submarine. It is about endurance. It is about human beings—young men, mechanics and electricians, sons and fathers—who stared down the enemy from the darkness of the deep. It is about their final days aboard a crippled boat, and the long, bitter months that followed in captivity. It is about Pappy Linder, who died a prisoner, but lived as a patriot.

The war is over. The guns are silent. But stories like this still call to us. The Grenadier may rest on the ocean floor, but her memory—like her crew—remains on eternal patrol. Let us remember them not as shadows in the deep, but as beacons of courage, sacrifice, and service.

Leave a comment